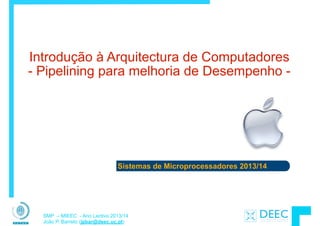

Este documento apresenta o plano de ensino para o curso "Sistemas de Microprocessadores" no ano lectivo de 2013/2014. Resume as seguintes informações essenciais:

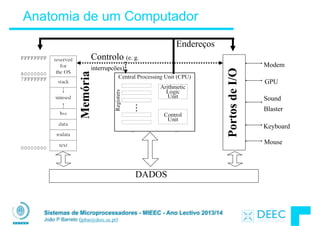

1) O curso será lecionado pelo professor João P. Barreto e abordará tópicos como programação em C e Assembly, arquitetura de computadores e introdução à programação de hardware.

2) As aulas consistirão em uma aula teórica e uma prática semanal, e a avaliação incluirá componentes teóricas e práticas ao

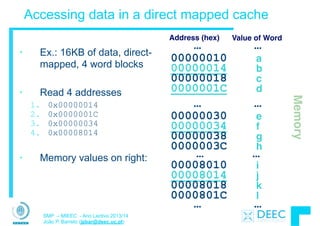

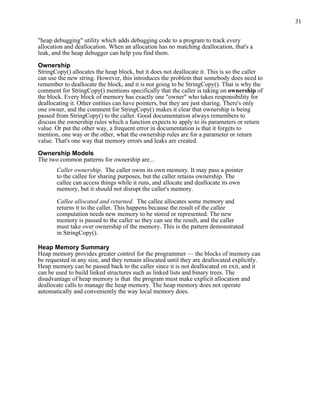

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

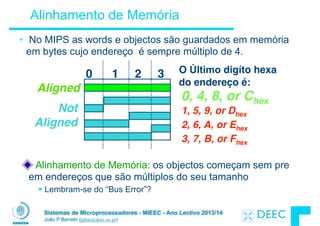

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Vamos fazer a ponte entre PC e LSD ...

lw $t0, 0($2)

lw $t1, 4($2)

sw $t1, 0($2)

sw $t0, 4($2)

High Level Language

Program (e.g., C)

Assembly Language

Program (e.g.,MIPS)

Machine Language

Program (MIPS)

Hardware Architecture Description

(Logic, Logisim, Verilog, etc.)

Compiler

Assembler

Machine

Interpretation

temp = v[k];!

v[k] = v[k+1];!

v[k+1] = temp;

0000 1001 1100 0110 1010 1111 0101 1000

1010 1111 0101 1000 0000 1001 1100 0110

1100 0110 1010 1111 0101 1000 0000 1001

0101 1000 0000 1001 1100 0110 1010 1111

Logic Circuit Description

(Logisim, etc.)

Architecture

Implementation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-5-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Sintaxe do C: Função main (revisão)

Para a função main aceitar parâmetros de entrada

passados pela linha de comando, utilize o seguinte:

!

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

!

O que é isto significa?

§ argc indica o número de strings na linha de comando (o

executável conta um, mais um por cada argumento adicional).

Ä Example: unix% sort myFile

§ argv é um ponteiro para uma array que contém as strings da

linha de comando (ver adiante).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-29-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Tabelas/Arrays (1/5)

Declaração:

int ar[2];

declara uma tabela de inteiros com 2 elementos. Uma

tabela/array é só um bloco de memória (neste caso de

8 bytes).

Declaração:

int ar[] = {795, 635};

declara e preenche uma tabela de inteiros de 2

elementos.

Acesso a elementos:

ar[num];

devolve o numº elemento (atenção o primeiro elemento

é acedido com num=0).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-36-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Arrays são (quase) idênticos a ponteiros

§ char *string e char string[] são declarações muito

semelhantes

§ As diferenças são subtis: incremento, declaração de

preenchimento de células, etc

!

Conceito Chave: Uma variável array (o "nome da

tabela") é um ponteiro para o primeiro elemento..

Tabelas/Arrays (2/5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-37-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

!

Consequências:

!

§ ar é uma variável array mas em muitos aspectos comporta-se

como um ponteiro

§ ar[0] é o mesmo que *ar

§ ar[2] é o mesmo que *(ar+2)

§ Podemos utilizar aritmética de ponteiros para aceder aos

elementos de uma tabela de forma mais conveniente.

!

O que está errado na seguinte função?

!

char *foo() {

char string[32]; ...;

return string;

}

Tabelas/Arrays (3/5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-38-320.jpg)

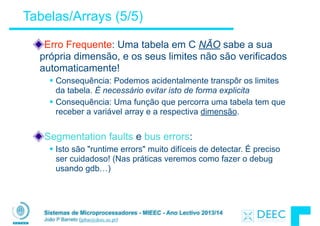

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Array de dimensão n; queremos aceder aos elementos

de 0 a n-1, usando como teste de saída a comparação

com o endereço da "casa" depois do fim do array.

int ar[10], *p, *q, sum = 0;

...

p = &ar[0]; q = &ar[10];

while (p != q)

sum += *p++; /* sum = sum + *p; p = p + 1; */

O C assume que depois da tabela continua a ser um

endereço válido, i.e., não causa um erro de bus ou um

segmentation fault

O que aconteceria se acrescentassemos a seguinte

instrução?

*q=20;

Tabelas/Arrays (4/5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-39-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Boas e Más Práticas

Má Prática

int i, ar[10];

for(i = 0; i < 10; i++){ ... }

!

Boa Prática

#define ARRAY_SIZE 10

int i, a[ARRAY_SIZE];

for(i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++){ ... }

!

Porquê? SINGLE SOURCE OF TRUTH

§ Evitar ter múltiplas cópias do número 10.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-42-320.jpg)

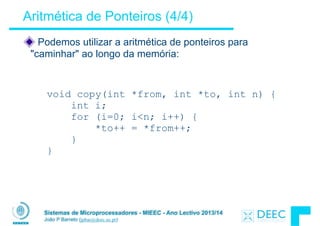

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

int get(int array[], int n)

{

return (array[n]);

/* OR */

return *(array + n);

}

Aritmética de Ponteiros (3/4)

O C sabe o tamanho daquilo que o ponteiro aponta (definido

implicitamente na declaração) – assim uma adição/subtracção

move o ponteiro o número adequado de bytes.

§ 1 byte para char, 4 bytes para int, etc.

!

As seguintes instruções são equivalentes:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-45-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Uma string em C é um array de carácteres.

char string[] = "abc";

!

Como é que sabemos quando uma string termina?

§ O último carácter é seguido de um byte a 0 (null terminator)

!

!

!

!

!

Um erro comum é esquecer de alocar um byte para o terminador

C Strings

int strlen(char s[])

{

int n = 0;

while (s[n] != 0) n++;

return n;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-48-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Arrays bi-dimensionais (1/2)

#define ROW_SIZE 3

#define COL_SIZE 2

!

...

char Mat[ROW_SIZE][COL_SIZE];

char aux=0;

int i, j;

for ( i=0; i<ROW_SIZE; i++)

for ( j=0; j<COL_SIZE; j++) {

Mat[i][j]=aux;

aux++;

}

...

6

5

4

3

2

1

0 Mat

Endereços

MEMÒRIA

0 1

2 3

4 5

Mat =](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-49-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Arrays bi-dimensionais (2/2)

O C arruma um array bi-dimensional empilhando as linhas

umas a seguir às outras.

!

O espaço total de memória ocupado é

ROW_SIZExCOL_SIZE

!

Temos que:

Mat[2][1] é o mesmo que Mat[2*COL_SIZE+1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-50-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Arrays vs. Ponteiros

O nome de um array é um ponteiro para o primeiro

elemento da tabela (indíce 0).

Um parâmetro tabela pode ser declarado como um

array ou um ponteiro.

int strlen(char s[])

{

int n = 0;

while (s[n] != 0)

n++;

return n;

}

int strlen(char *s)

{

int n = 0;

while (s[n] != 0)

n++;

return n;

}

Pode ser escrito:

while (s[n])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-51-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Alocação dinâmica de memória (1/4)

Em C existe a função sizeof() que dá a dimensão em bytes do tipo ou

variável que é passada como parâmetro.

!

Partir do príncipio que conhecemos o tamanho dos objectos pode dar

origem a erros e é uma má prática, por isso utilize sizeof(type)

§ Há muitos anos o tamanho de um int eram 16 bits, e muitos

programas foram escritos com este pressuposto.

§ Qual é o tamanho actual de um int?

!

“sizeof” determina o tamanho para arrays:

int ar[3]; // Or: int ar[] = {54, 47, 99}

sizeof(ar) ⇒ 12

§ …bem como para arrays cujo tamanho é definido em run-time:

int n = 3;

int ar[n]; // Or: int ar[fun_that_returns_3()];

sizeof(ar) ⇒ 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-55-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Duferença súbtil entre arrays e ponteiros

void foo() {

int *p, *q, x, a[1]; // a[] = {3} also works here

p = (int *) malloc (sizeof(int));

q = &x;

*p = 1; // p[0] would also work here

*q = 2; // q[0] would also work here

*a = 3; // a[0] would also work here

printf("*p:%u, p:%u, &p:%un", *p, p, &p);

printf("*q:%u, q:%u, &q:%un", *q, q, &q);

printf("*a:%u, a:%u, &a:%un", *a, a, &a);

}

? ? ......

12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 52 56 60 64 68 ...

p q x a

? ? ?

unnamed-malloc-space

52 32 2 3 1

*p:1, p:52, &p:24

*q:2, q:32, &q:28

*a:3, a:36, &a:36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-59-320.jpg)

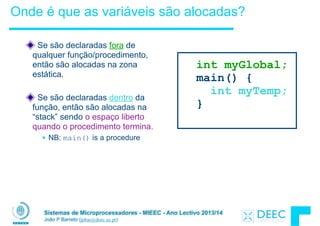

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Variáveis Globais

A declaração de ponteiros não aloca memória

em frente do ponteiro

Até agora falámos de duas maneiras

diferentes de alocar memória:

§ Declaração de variáveis locais

int i; char *string; int ar[n];

§ Alocação dinâmica em runtime usando "malloc"

ptr = (struct Node *) malloc(sizeof(struct

Node)*n);

Existe uma terceira possibilidade ...

§ Declaração de variáveis fora de uma função (i.e.

antes do main)

Ä É similar às variavéis locais mas tem um âmbito

global, podendo ser lida e escrita de qualquer ponto

do programa

int myGlobal;

main() {

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-65-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

QUIZ do Intervalo

int main(void){

int A[] = {5,10};

int *p = A;

printf(“%u %d %d %dn”,p,*p,A[0],A[1]);

p = p + 1;

printf(“%u %d %d %dn”,p,*p,A[0],A[1]);

*p = *p + 1;

printf(“%u %d %d %dn”,p,*p,A[0],A[1]);

}

Se o primeiro printf mostrar 100 5 5 10, qual será o output dos outros dois printf ?

1: 101 10 5 10 then 101 11 5 11

2: 104 10 5 10 then 104 11 5 11

3: 101 <other> 5 10 then 101 <3-others>

4: 104 <other> 5 10 then 104 <3-others>

5: Um dos dois printfs causa um ERROR

6: Rendo-me!

A[1]

5 10

A[0] p](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-79-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Endereçamento: Byte vs. word

• Todas as words em memória têm um endereço.

!

• Os primeiros computadores referenciavam as words da mesma

forma que o C numera elementos num array:

§ Memory[0], Memory[1], Memory[2], …

“endereço” de uma word

No entanto os computadores precisam de referenciar

simultaneamente bytes e words (4 bytes/word)

!

Hoje em dia todas as arquitecturas endereçam a memória em bytes

(i.e.,“Byte Addressed”). Assim para aceder a words de 32-bits os

endereços têm que dar saltos de 4 bytes

§ Memory[0], Memory[4], Memory[8], …](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-127-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

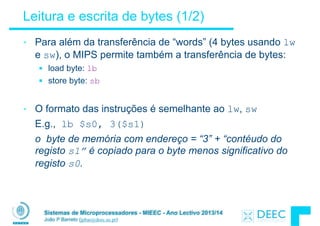

Compilação de Acessos à Memória

• Qual o offset que devemos usar com lw para aceder a

A[5], sendo A uma tabela de int em C?

§ Para seleccionar A[5]temos que 4x5=20: byte v. word

!

• Desafio: Compile a instrução à mão usando registos:

§ g = h + A[5]com g: $s1, h: $s2, endereço base de A: $s3

!

§ Transfira da memória para o registo:

!! lw $t0,20($s3) # $t0 gets A[5]

Ä Adicione 20 a $s3 para seleccionar A[5]e coloque em $t0

!

§ Adicione o resutado a h e coloque em g

! add $s1,$s2,$t0 # $s1 = h+A[5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-128-320.jpg)

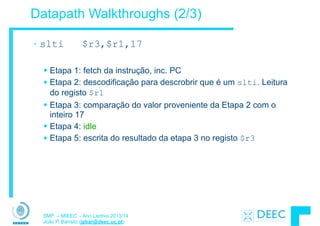

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

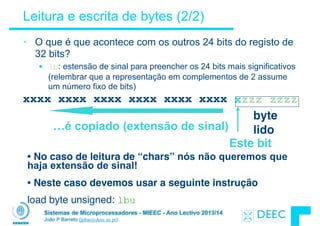

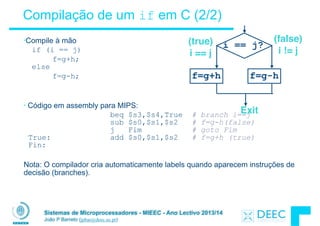

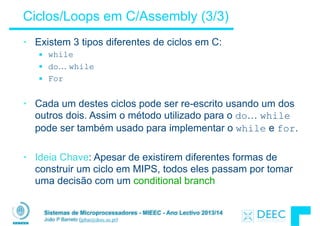

Ciclos (Loops) em C/Assembly (1/3)

• Ciclo simples em C; A[] é um array de ints

do {

g = g + A[i];

i = i + j;}

while (i != h);

• Re-esrevendo de uma forma deselegante:

Loop: g = g + A[i];

i = i + j;

if (i != h)

goto Loop;

• Assumindo agora o seguinte mapeamento variável-registo:

g, h, i, j, base of A

$s1, $s2, $s3, $s4, $s5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-156-320.jpg)

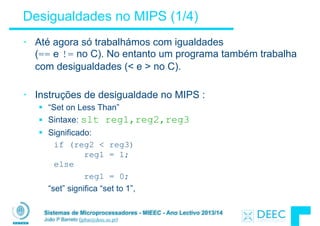

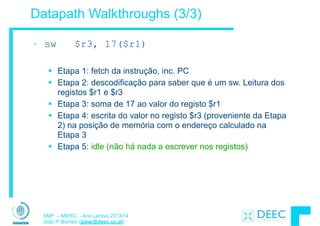

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Ciclos (Loops) em C/Assembly (2/3)

!

• Código compilado para MIPS:

Loop: sll $t1,$s3,2 #$t1= 4*i

add $t1,$t1,$s5 #$t1=addr A

lw $t1,0($t1) #$t1=A[i]

add $s1,$s1,$t1 #g=g+A[i]

add $s3,$s3,$s4 #i=i+j

bne $s3,$s2,Loop # goto Loop

# if i!=h

• Código original (guia):

Loop: g = g + A[i];

i = i + j;

if (i != h) goto Loop;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-157-320.jpg)

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

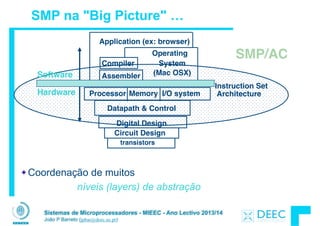

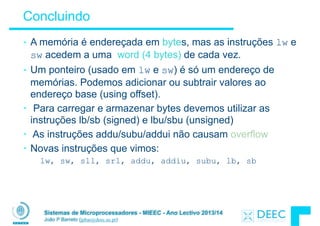

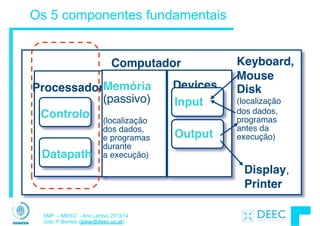

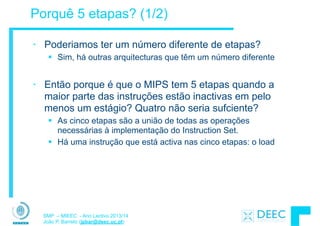

Níveis de representação num computador

High Level Language

Program (e.g., C)

Assembly Language

Program (e.g.,MIPS)

Machine Language

Program (MIPS)

Hardware Architecture Description

(e.g., block diagrams)

Compiler

Assembler

Machine

Interpretation

temp = v[k];

v[k] = v[k+1];

v[k+1] = temp;

lw $t0, 0($2)

lw $t1, 4($2)

sw $t1, 0($2)

sw $t0, 4($2)

0000 1001 1100 0110 1010 1111 0101 1000

1010 1111 0101 1000 0000 1001 1100 0110

1100 0110 1010 1111 0101 1000 0000 1001

0101 1000 0000 1001 1100 0110 1010 1111

Logic Circuit Description (Circuit

Schematic Diagrams)

Architecture

Implementation

Register File

ALU

PPP

LSD

SMP](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-225-320.jpg)

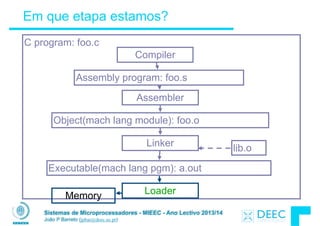

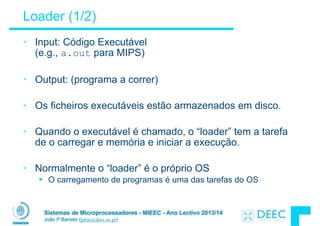

![Sistemas de Microprocessadores - MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

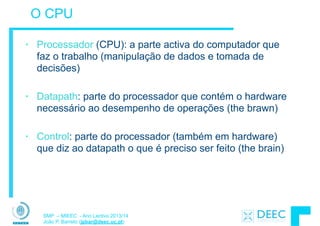

Exemplo: C ⇒ Asm ⇒ Obj ⇒ Exe ⇒ Run

#include <stdio.h>

int main (int argc, char *argv[]) {

int i, sum = 0;

for (i = 0; i <= 100; i++)

sum = sum + i * i;

printf ("The sum of sq from 0 .. 100 is %dn", sum);

}

Código fonte do programa em C : prog.c

“printf” está em “libc”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-297-320.jpg)

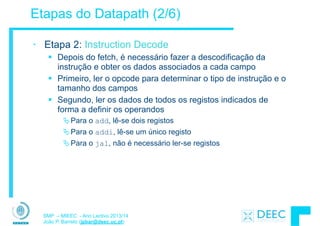

![SMP – MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P. Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Exemplo: instrução add

PC

instruction

memory

+4

registers

ALU

Data

memory

imm

2

1

3

addr3,r1,r2

reg[1]+reg[2]

reg[2]

reg[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-320-320.jpg)

![SMP – MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P. Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Exemplo: Instrução slti

PC

instruction

memory

+4

registers

ALU

Data

memory

imm

3

1

x

sltir3,r1,17

reg[1]<17?

17

reg[1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-322-320.jpg)

![SMP – MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P. Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Exemplo: Instrução sw

PC

instruction

memory

+4

registers

ALU

Data

memory

imm

3

1

x

SWr3,17(r1)

reg[1]+17

17

reg[1]

MEM[r1+17]<=r3

reg[3]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-324-320.jpg)

![SMP – MIEEC - Ano Lectivo 2013/14

João P. Barreto (jpbar@deec.uc.pt)

Example: lw Instruction

PC

instruction

memory

+4

registers

ALU

Data

memory

imm

3

1

x

LWr3,17(r1)

reg[1]+17

17

reg[1]

MEM[r1+17]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-327-320.jpg)

![12

Here is a more detailed version of the rules of local storage...

1. When a function is called, memory is allocated for all of its locals. In other

words, when the flow of control hits the starting '{' for the function, all of

its locals are allocated memory. Parameters such as num and local

variables such as result in the above example both count as locals. The

only difference between parameters and local variables is that parameters

start out with a value copied from the caller while local variables start with

random initial values. This article mostly uses simple int variables for its

examples, however local allocation works for any type: structs, arrays...

these can all be allocated locally.

2. The memory for the locals continues to be allocated so long as the thread

of control is within the owning function. Locals continue to exist even if

the function temporarily passes off the thread of control by calling another

function. The locals exist undisturbed through all of this.

3. Finally, when the function finishes and exits, its locals are deallocated.

This makes sense in a way — suppose the locals were somehow to

continue to exist — how could the code even refer to them? The names

like num and result only make sense within the body of Square()

anyway. Once the flow of control leaves that body, there is no way to refer

to the locals even if they were allocated. That locals are available

("scoped") only within their owning function is known as "lexical

scoping" and pretty much all languages do it that way now.

Small Locals Example

Here is a simple example of the lifetime of local storage...

void Foo(int a) { // (1) Locals (a, b, i, scores) allocated when Foo runs

int i;

float scores[100]; // This array of 100 floats is allocated locally.

a = a + 1; // (2) Local storage is used by the computation

for (i=0; i<a; i++) {

Bar(i + a); // (3) Locals continue to exist undisturbed,

} // even during calls to other functions.

} // (4) The locals are all deallocated when the function exits.

Large Locals Example

Here is a larger example which shows how the simple rule "the locals are allocated when

their function begins running and are deallocated when it exits" can build more complex

behavior. You will need a firm grasp of how local allocation works to understand the

material in sections 3 and 4 later.

The drawing shows the sequence of allocations and deallocations which result when the

function X() calls the function Y() twice. The points in time T1, T2, etc. are marked in

the code and the state of memory at that time is shown in the drawing.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-472-320.jpg)

![20

Simple Reference Parameter Example — Swap()

The standard example of reference parameters is a Swap() function which exchanges the

values of two ints. It's a simple function, but it does need to change the caller's memory

which is the key feature of pass by reference.

Swap() Function

The values of interest for Swap() are two ints. Therefore, Swap() does not take ints

as its parameters. It takes a pointers to int — (int*)'s. In the body of Swap() the

parameters, a and b, are dereferenced with * to get at the actual (int) values of interest.

void Swap(int* a, int* b) {

int temp;

temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

Swap() Caller

To call Swap(), the caller must pass pointers to the values of interest...

void SwapCaller() {

int x = 1;

int y = 2;

Swap(&x, &y); // Use & to pass pointers to the int values of interest

// (x and y).

}

ba temp 1

SwapCaller()

Swap()

2 1y1 2x

The parameters to Swap() are pointers to values of interest which are back in the caller's

locals. The Swap() code can dereference the pointers to get back to the caller's memory to

exchange the values. In this case, Swap() follows the pointers to exchange the values in

the variables x and y back in SwapCaller(). Swap() will exchange any two ints given

pointers to those two ints.

Swap() With Arrays

Just to demonstrate that the value of interest does not need to be a simple variable, here's

a call to Swap() to exchange the first and last ints in an array. Swap() takes int*'s, but

the ints can be anywhere. An int inside an array is still an int.

void SwapCaller2() {

int scores[10];

scores[0] = 1;

scores[9[ = 2;

Swap(&(scores[0]), &(scores[9]));// the ints of interest do not need to be

// simple variables -- they can be any int. The caller is responsible

// for computing a pointer to the int.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-480-320.jpg)

![29

• At T1 before the call to malloc(), intPtr is uninitialized does not have a

pointee — at this point intPtr "bad" in the same sense as discussed in

Section 1. As before, dereferencing such an uninitialized pointer is a

common, but catastrophic error. Sometimes this error will crash

immediately (lucky). Other times it will just slightly corrupt a random data

structure (unlucky).

• The call to free() deallocates the pointee as shown at T3. Dereferencing

the pointer after the pointee has been deallocated is an error.

Unfortunately, this error will almost never be flagged as an immediate

run-time error. 99% of the time the dereference will produce reasonable

results 1% of the time the dereference will produce slightly wrong results.

Ironically, such a rarely appearing bug is the most difficult type to track

down.

• When the function exits, its local variable intPtr will be automatically

deallocated following the usual rules for local variables (Section 2). So

this function has tidy memory behavior — all of the memory it allocates

while running (its local variable, its one heap block) is deallocated by the

time it exits.

Heap Array

In the C language, it's convenient to allocate an array in the heap, since C can treat any

pointer as an array. The size of the array memory block is the size of each element (as

computed by the sizeof() operator) multiplied by the number of elements (See CS

Education Library/101 The C Language, for a complete discussion of C, and arrays and

pointers in particular). So the following code heap allocates an array of 100 struct

fraction's in the heap, sets them all to 22/7, and deallocates the heap array...

void HeapArray() {

struct fraction* fracts;

int i;

// allocate the array

fracts = malloc(sizeof(struct fraction) * 100);

// use it like an array -- in this case set them all to 22/7

for (i=0; i<99; i++) {

fracts[i].numerator = 22;

fracts[i].denominator = 7;

}

// Deallocate the whole array

free(fracts);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-489-320.jpg)

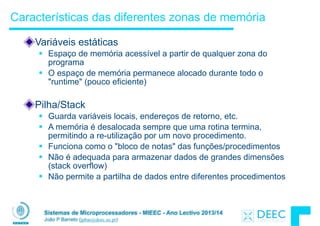

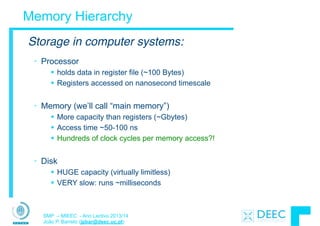

![Chapter 10

Storage Management

[These notes are slightly modified from notes on C storage allocation from the Fall

1991 offering of CS60C. The language used is C, not Java.]

10.1 Classification of storage

In languages like C or Java, the storage used by a program generally comes in three

categories.

Static storage. This refers to variables—generally given names by declarations—

whose lifetime by definition encompasses the entire program’s execution.

Local storage. Variables—also usually named in declarations—whose lifetimes

end after the execution of some function or block.

Dynamic storage. Variables (generally anonymous) whose lifetime begins with

the evaluation of a specific statement or expression and ends either at an

explicit deallocation statement or at program termination.

For example, in Java, static variables are introduced by as static fields in classes. C

and C++ also allow for static variables in functions and outside classes and functions

(at the “outer level” where they are in effect static fields in a giant anonymous class).

For example,

int rand(void) /* C code */

{

static int lastValue = 42;

extern int randomStatistics;

...

}

Here, there is a single variable lastValue and a single variable randomStatistics

that retain their last values from call to call. It is true that only the function rand

143](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-492-320.jpg)

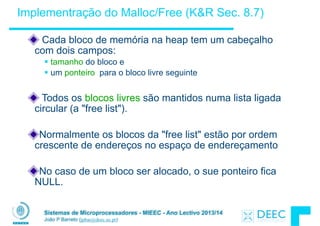

![148 CHAPTER 10. STORAGE MANAGEMENT

#define _ADMIN_WORD(X) ((AdminWord *) (X))[-1]

/** The minimum size of a free block. */

#define MIN_FREE_BLOCK (3 * sizeof(Address))

/** True iff the block at location X is a free block. */

#define isFree(X) (_ADMIN_WORD(X).isFree)

/** True iff the block just before the block at location X is a free

* block. */

#define precedingIsFree(X) (_ADMIN_WORD(X).precedingIsFree)

/** The size of the block at X, including the administrative word. */

#define blockSize(X) (_ADMIN_WORD(X).size)

/** A pointer to the block next in memory after the one at X. */

#define followingBlock(X) ((Address) (X) + blockSize(X))

/** If X points to a free block, then the link to the next block in the

* free list is at location X, and a back link to the previous block

* in the free list is at the end of the block pointed to by X.

* If precedingIsFree(X), then the back link for the free block

* that precedes X in memory is immediately before the

* administrative block for X. Therefore, one can find the address

* of the free block that precedes X in memory by the circuitous

* route of picking up this back link and then following the

* forward from there. */

#define freeNext(X)

((Address*) (X))[0]

#define precedingBackLink(X)

((Address*) (X))[-2]

#define freePrev(X)

precedingBackLink(followingBlock(X))

#define precedingBlock(X)

freeNext(precedingBackLink(X))

Address FREE_LIST;

Initially, the allocation routines reserve a large, contiguous block of storage,

allocating a dummy sentinel block at the high end to prevent the free routine

from attempting to coalesce a newly-freed block with the storage that follows. The

freeNext and freePrev pointers for the remaining initial free block are initialized

to point to the block itself, creating a one-element circular, doubly-linked list.

Allocation. To allocate a block, we use the following procedure (text in italics

for missing code, which is left to the reader to supply).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-497-320.jpg)

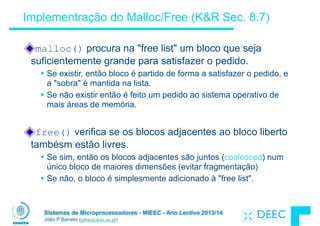

![152 CHAPTER 10. STORAGE MANAGEMENT

10.3.2 Buddy system method

When there is a single free list to search, the time required to perform allocation

cannot easily be bounded. In some applications, this may be a problem. The buddy

system provides for allocation and freeing of storage in time O(lg N), where N is

the size of storage. It allocates storage in units of 2k storage units (bytes, words,

whatever) for k ≥ k0, where 2k0 storage units is the minimum needed to hold

forward and backward pointers for a free list (this information appears only in free

blocks).

The idea is to treat the allocatable storage area as an array of storage units,

indexed 0 through 2m 1. A block (free or allocated) of size 2k will always start at

an index in this array that is evenly divisible by 2k. Free blocks are only coalesced

with other free blocks of the same size, and only in such a way as to preserve the

property that each free block starts at an index position that is divisible by its size.

For example, suppose that a block of size 16 becomes free and that it starts at

index position 48 in the storage array. This block may be merged with a block of

size 16 that starts in position 32. It may not be merged with a block of size 16

that starts in position 64, because the resulting block would be of size 32, and such

blocks may only start at positions divisible by 32; merging our block at 48 with one

at 64 would result in a block of size 32 that started at position 48, which is not

allowed. We say that the blocks of size 16 at positions 32 and 48 are buddies, while

those at 48 and 64 are not.

Thus, the rule is that a free block may only be coalesced with its buddy (and

only if that block is free). The calculation of one’s buddy’s index is quite easy, if a

bit obscure. The buddy of a block of size 2k at an index X begins at index X ⊕ 2k,

where ‘⊕’ computes the exclusive or of the binary representations of its operands

(the ‘string^’ operator in C).

Each free block contains forward and backward links for inclusion in a free list.

The system maintains four arrays.

MEMORY is the actual allocatable storage (containing 2m StorageUnits, where

the type StorageUnit is typically something like char).

FREE LIST is an array of FreeBlocks with FREE_LIST[k] being the sentinel

for the list of free blocks of size 2k. Each list is circular and doubly-linked.

Initially, FreeBlock[m] contains the entire block of allocatable storage (of size

2m) and all other free lists contain only their sentinel nodes (are empty, in

other words).

IS FREE is an array of true/false values, with IS_FREE[$X$] being true iff

X is the index of a free block. Since each element is either true or false,

this array may be represented compactly—perhaps as a bit vector. Initially,

IS_FREE[0] is true and all others are false.

SIZE is an array of integers in the range 0 to m. If there is a block (free or

allocated) of size 2k that begins at location X, then SIZE[$X$] contains k.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-501-320.jpg)

![10.3. DYNAMIC STORAGE ALLOCATION WITH EXPLICIT FREEING 153

Because these values tend to be small, and because X will always be divisible

by 2k0 , it is possible to represent SIZE compactly. Initially, SIZE[0] is m.

Allocation. To allocate under the buddy system, we first round the size request

up to a power of 2. If no block of the desired size is free, we allocate a block of

double the size (recursively) and then break it into its constituent buddies, putting

one of them back on the free list and returning the other as the desired allocation.

unsigned int buddyAlloc(unsigned int N)

/* Return the index in MEMORY of a new block of storage at least */

/* N storage units large. */

{

Choose the minimum k ≥ k0 with 2k ≥ N and set N to 2k.

if (k > m)

ERROR: insufficient storage.

if (isEmpty(FREE_LIST[k])) {

unsigned int R = buddyAlloc(2*N);

IS_FREE[R] = TRUE;

SIZE[R] = k;

Add the block at R to FREE LIST[k].

return R+N; /* i.e., the second half of the size 2N block at R */

}

else {

Remove an item, R, from FREE LIST[k].

IS_FREE[R] = FALSE;

return R;

}

}

Address malloc(unsigned int N)

{

return & MEMORY[buddyAlloc(N)];

}

Freeing. To see if a newly-freed block may be coalesced with its buddy, we first

see if the block at the buddy’s location is free, and then see if that block has the

right size (the buddy may have been broken down to satisfy a request for something

smaller).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-502-320.jpg)

![154 CHAPTER 10. STORAGE MANAGEMENT

/** Free the storage at index L in MEMORY. */

void buddyFree(unsigned int L)

{

int k = SIZE[L];

int N = 1 << k;

unsigned int Lbuddy = L string^ N;

if (k < m && IS_FREE[Lbuddy] && SIZE[Lbuddy] == k) {

Remove Lbuddy from FREE LIST[k]

IS_FREE[Lbuddy] = FALSE;

if (L > Lbuddy)

L = Lbuddy;

SIZE[L] = k+1;

buddyFree(L); /* recursively free the coalesced block */

}

else {

IS_FREE[L] = TRUE;

Add L to FREE LIST[k];

}

}

void free(Address X)

{

unsigned int L = (StorageUnit*) X - (StorageUnit*) MEMORY;

if (X == NULL || IS_FREE[L])

return;

buddyFree(L);

}

10.3.3 “Quick fit”

The use of an array of free lists in the buddy system suggests a simple way to

speed up allocation and deallocation. When there are certain sizes of object that

you often request, maintain a separate free list for each of these sizes. Requests for

other sizes may be satisfied with a heterogeneous list, as described in the sections

above. Free items on the one-size lists need not be coalesced (except perhaps in

an emergency, when there is insufficient storage to meet a larger request), and no

searching is needed to find an item of one of those sizes on a non-empty list. This

means, of course, that allocation and freeing go very fast for those sizes. The term

quick-fit has been used to describe this scheme.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-503-320.jpg)

![10.4. AUTOMATIC FREEING 155

10.4 Automatic Freeing

There are two problems with having the programmer free dynamic storage explicitly.

First, it complicates and obscures programs to do so. Second, it is prone to error.

Suppose, for example, that I introduce a string module into C. It provides a type,

String, whose variables may contain arbitrary strings, of any length, and whose

operations allow the programmer to form catenations, substrings, and so forth. I’d

like to use String variables as conveniently as if they were integers. To make good

use of space, it is convenient to use dynamic storage. This presents a problem,

however. In contrast to the situation with int variables, my String variables don’t

entirely vanish when I exit the procedure that declares them. I must explicitly

deallocate them—my string module will have provided a deallocation procedure, of

course, but I (the programmer) must still write something. Worse yet, consider a

procedure such as this.

/** Return the concatenation of the strings in X. */

String concatList(String X[], int N)

{

int i;

String R = nullString();

for (i = 0; i < N; i += 1)

R = concat(R, X[i]);

return R;

}

This seems innocuous, but it is unlikely to work well. The problem is that the

function concat does not know that the storage used by its first operand can be

deallocated immediately after use (since the result of concat is going back into R).

The programmer must explicitly deallocate each intermediate value of R instead,

which will complicate this function considerably.

Perhaps the most common error found in programs that do explicit freeing is the

memory leak: storage that is never deallocated, even after it is no longer needed.

Other errors are possible, as well; attempts to access storage after it has been freed

can lead to extremely obscure errors (I suspect, however, that these bugs are less

common than memory leaks).

These considerations lead us to consider methods for automatically freeing dy-

namic storage that is no longer needed. This generally translates to dynamic stor-

age that is no longer reachable—that the program can no longer reference since no

pointers lead to it (directly or indirectly) from any named variables the program

can access. Such storage is called garbage, and the process of reclaiming it garbage

collection4.

Some assumptions. Automatic storage reclamation generally requires some co¨operation

from the compiler and the programming language being used. All of the methods

4

Some authors reserve the term “garbage collection” for methods that use marking (see below),

excluding reference counting. Here, I will use the term for all forms of automatic reclamation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/merged-160129231445/85/Sistemas-de-Microprocessadores-2013-2014-504-320.jpg)