Klengel, Schumann - Romantic Cello Concertos (Encarte).pdf

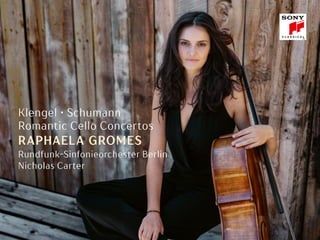

- 1. Klengel • Schumann Romantic Cello Concertos RAPHAELA GROMES Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Nicholas Carter

- 2. Julius Klengel (1859–1933) Concerto for Cello and Orchestra no. 3 in A Minor, op. 31 Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester Nr. 3 a-Moll op. 31 1 I. Allegro non troppo 7:52 2 II. Intermezzo. Allegretto 4:16 3 Cadenza 3:41 4 III. Finale. Vivace 6:12 World premiere recording / Weltersteinspielung Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Romanze for Cello and Orchestra in F Major, WoO 75 / TrV 118 Romanze für Violoncello und Orchester F-Dur o. Op. 75 / TrV 118 5 Andante cantabile 8:25 Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in A Minor, op. 129 Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester a-Moll op. 129 6 I. Nicht zu schnell 10:58 7 II. Langsam 3:48 8 III. Sehr lebhaft 7:42 9 “Widmung” from the song cycle Myrthen, op. 25 2:06 „Widmung“ aus dem Liederzyklus Myrthen op. 25 Clara Wieck-Schumann (1819–1896) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in A Minor, op. 7 Konzert für Klavier und Orchester a-Moll op. 7 10 II. Romanze for Cello and Piano. Andante ma non troppo con grazia 2:53 Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) 11 Hungarian Dance no. 5 2:49 Ungarischer Tanz Nr. 5 Arranged for cello and piano by Alfredo Piatti Bearbeitet für Violoncello und Klavier von Alfredo Piatti Raphaela Gromes, cello/Violoncello Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin (RSB) Nicholas Carter, conductor/Dirigent Julian Riem, piano/Klavier (Tracks 9-11) Total Time: 60:42 Tracks 1-8 recorded on 24-27th of April 2018, in Haus des Rundfunks, Großer Sendesaal, Berlin, Germany Recording Producer & Editing: Florian B. Schmidt Tracks 9-11 recorded on 26th of July 2020, in Groundlift Studio, Alten Brauerei Stegen, Germany Recording Producer & Editing: Marie-Josefin Melchior Executive Producers: Stefan Lang (DLF Kultur) & Michael Brüggemann (Sony Classical) Photos Gromes & Riem: © Sammy Hart Photo Orchestra & Carter: © Simon Pauly Artwork: Roland Demus A Co-production with Deutschlandfunk Kultur and Rundfunk-Orchester und -Chöre gGmbH Berlin (ROC) P 2020 Deutschlandradio / ROC / Sony Music Entertainment Germany GmbH C 2020 Sony Music Entertainment Germany GmbH www.raphaelagromes.de www.rsb-online.de www.askonasholt.com/artists/nicholas-carter www.sonyclassical.com/de

- 3. The cello and Romanticism The cello and Romanticism are so inextricably linked in people’s minds that the cello is even regarded as the most Romantic of all musical instruments. This perception may stem from the similarities between the warmth of the instrument’s timbre and the sound of the human voice, a perception that in turn reflects the Romantics’ tendency to indulge in poetical flights of fancy and cantabile expression. There is also the enormous diversity of the cello’s sound world, which extends over a magnificent compass of almost five octaves, allowing for full-bodied power in its lowest register, a rich palette of expressive tone colours in its middle register and highly effective climaxes in its violin-like upper register. These aristo- cratic advantages explain the instrument’s well-nigh incalculable presence in Romantic chamber music. It is astonishing, conversely, that the cello was unable to play a leading role as a concerto instrument in the nineteenth century, when the piano and the violin remained its most popular rivals. As a result, even today, only a handful of cello concertos cast their effulgent light over the century as a whole. Yet this state of affairs means that a whole series of equally outstanding pieces have been unjustly neglected and in some cases forgotten in their entirety. Raphaela Gromes has already rediscovered a number of exciting pieces for her previous releases on the Sony Classical label, and we must now be grateful to her for recording Julius Klengel’s Third Cello Concerto, a work published by Boosey & Hawkes in 1895 and now appearing on this album for the very first time in the form of a world premiere recording. Julius Klengel: Cello Concerto no. 3 in A Minor, op. 31 World premiere recording The violoncellist and composer Julius Klengel (1859–1933) was a member of a large family of German musicians and in his day one of the leading figures in the musical life of Leipzig. He joined the Gewandhaus Orchestra at the age of only fifteen and by the following year he was already performing concertos all over Germany as an acclaimed prodigy. At the age of twenty-two, he became the orchestra’s principal cellist and a member of the famous Gewandhaus Quartet. He remained with the Gewandhaus Orchestra until 1924, working under three of its greatest conductors, Carl Reinecke, Arthur Nikisch and, for a number of years, Wilhelm Furtwängler. Despite his extensive commitments as a travelling virtuoso and as a well-respected teacher at the Leipzig Conservatory, where he was known as the “European cellist-maker”, he also left a substantial body of works, most of them for the cello. He additionally wrote pieces for several cellos designed to help his students with their ensemble playing. His Hymn for twelve cellos remains popular to this day. Among his larger works are four cello concertos, two double concertos for two cellos and two double concertos for violin and cello as well as a serenade for strings. For inexplicable reasons, Klengel’s Cello Concerto no. 3, op. 31 was neglected for a long time until Raphaela Gromes recently woke it from its slumbers. It was first performed at the Gewandhaus Orchestra’s thirteenth subscription concert on 21 January 1892, when Klengel himself took the solo part and the conductor was Carl Reinecke. According to the critic Gustav Schlemüller writing in the Leipziger Anzeiger, “the applause was tempestu- ous in the extreme and was followed by several shouts of ‘hurrah’.” The piece, Schlemüller went on, “may be regarded as a genuine enrichment of the repertory” since it “everywhere avoids trivialities and is unique in terms of its cantilenas and its passage-work.” The Neue Zeitschrift für Musik that Schumann had founded in 1834 likewise reviewed the new piece in its edition of 27 January 1892: “The Cello Concerto is in three movements: an Allegro non troppo, an Intermezzo-Allegretto and a Finale-Vivace. However, these movements are not separate, self-contained entities, as is the case with most earlier concertos. Rather, they are linked together organically and by means of modulatory procedures to create a single unit. Their content, too, is developed along unconventional lines, with passages of great technical difficulty alternating with sustained cantilenas. A handful of fanfares seemed to invite us to a tournament or to go into battle, but everything ended peacefully, and the virtuoso-cum-composer was rewarded at the end with plentiful applause and with calls to return to the stage.” Today this work represents a genuine enrichment of the Romantic cello repertory, its vir- tuoso elegance revealing the characteristic mastery of an authoritative practitioner on his instrument. Marked Allegro non troppo, the opening movement proceeds along altogether exemplary lines, the orchestral cellos and bassoon introducing the motifs from the main theme in the semi-darkness of their lower register. When the solo cello enters, it strikes an improvisatory note before stating the beautiful songlike theme. This theme is virtuosically spun out, leading in turn to a second and no less songlike subject that rises up to the spars- est of accompaniments. A further virtuoso passage for the soloist is followed by a jubilant gesture in the orchestra, bringing this section to an end. Much to the listener’s surprise it is followed neither by a development section nor by a recapitulation. A relatively lyrical commentary by the soloist creates the impression of a transition to the second move- ment, which is marked Allegretto. This movement develops along the lines of a three-part Scherzo–Intermezzo, in which the solo cello adds a cheerful commentary to the “trumpet fanfares” mentioned by Johann Schucht in his review for the Neue Zeitschrift. The under- lying triplet rhythm even hints at a graceful waltz before a large-scale cadenza picks up the wistful motifs of the opening movement and brings this section to an end. The third movement is an Allegro vivace whose lively central theme suggests possible Hungarian influence. It is embellished by the soloist in a delightfully playful way. The orchestra too presents a dancelike theme that is easily recognizable by its descending scalar motif. We then hear a reminiscence of the opening movement’s second subject, after which a coda concludes the work with a tutti restatement of the theme. Richard Strauss: Romanze in F Major, WoO 75 / TrV 118 The present Romanze is one of many pieces that Strauss wrote during his youth. Barely nineteen years old at the time, he not only experimented as a composer with various genres and instruments but also gave early proof of the hallmarks of his genius. Among these works are a violin concerto, two symphonies, a wind serenade for thirteen instruments that has

- 4. entrusted him with the task of preparing the solo part from a technical point of view. But the hope that he would be able to premiere the work in Düsseldorf with Bockmühl proved misplaced as the cellist kept on finding new excuses to avoid performing the piece. Schumann deliberately called the work a Concertstück since it does not conform to his own formal view on “how the orchestra is to be combined” with the solo instrument. The first two movements are dominated by the solo instrument, which is virtuosic throughout, even denying the orchestra the chance of an exposition in the opening movement and forcing it back into the role of a mere accompanist in the second movement. In spite of this the work is not a typical virtuoso concerto, its element of virtuosity being subordinated to an expressivity sustained by its flowing melodic lines, so that even today the work towers above the rest of a repertory of more than manageable proportions. Formally speaking, Schumann’s Cello Concerto has a three-part structure, yet thanks to its fluid transitions the thematic material, which recurs in various guises in all three movements, and the integra- tion provided by the development principle blend together to create a single movement. From start to finish the work as a whole is lit by a sense of poetry. The opening move- ment is marked Nicht zu schnell (Not too fast). At its start the solo cello enters after a brief orchestral cadence and presents the elegiac main theme, which is almost thirty bars long. Although the following orchestral tutti picks up segments of this theme, it also inaugurates a process that recalls nothing so much as a development section and leaves its mark on the movement as a whole, adopting an almost improvisatory approach to the plentiful motivic material. The usual cadenza for the soloist is replaced – surprisingly – by a tender cello cantilena that also provides a bridge to the second movement, marked Langsam – Etwas lebhafter – Tempo I – Schneller (Slow – Somewhat livelier – Tempo I – Quicker). A heartfelt theme is reworked in multiple ways, allowing it to reveal the whole of its emotional appeal and providing a sense of calm and balance to offset the dynamic outer movements. The piz- zicato accompaniment of the strings and the prominence of a second cello part alongside the solo line serve to underscore the cantabile character of this intermezzo. The third move- ment is headed Sehr lebhaft – Im Tempo – Schneller (Very lively – In tempo – quicker) and follows on without a break, a passage for the solo cello providing a link between the two. Formally speaking, it resembles a rondo and is characterized by its earthy head motif that leaves its mark on the episode-like interludes as well. The solo instrument and the orchestra are intertwined in this movement, each of them being invested with a very similar weight. For the present recording with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Raphaela Gromes has worked with the young Australian conductor Nicholas Carter to produce a translucent, chamber-like interpretation of the piece. Encores The successful duo of Raphaela Gromes and Julian Riem continues to enrich the Romantic chamber music repertory with more and more new ideas and new arrangements, including the three encores featured in the present release: two are compositions by the “Romantic Titans” Schumann and Brahms, while the third is by the hugely talented Clara Wieck, who later married Schumann and became a close friend of Brahms. Raphaela Gromes

- 5. lost none of its popularity and his First Horn Concerto, which the then eighteen-year-old composer wrote for his father’s sixtieth birthday. One of the most striking features of the works of this period is their association with leading figures in their young composer’s life. One such piece is his Romanze in F Major for cello and orchestra, which he completed on 17 June 1883. There is no doubt that his already astonishing stylistic assurance in his han- dling of the cello was due in no small part to his close contact with the famous principal cellist of the Royal Court Orchestra in Munich, Hanuš Wihan. Strauss had been only sixteen when he dedicated his Cello Sonata, op. 6 TrV 115 to his “dear friend”. Its initial version of 1880–81 was thoroughly revised and published by Joseph Aibl in Vienna shortly before he completed the present Romanze. Raphaela Gromes and Julian Riem presented the world premiere recording of its initial version in early 2020. Hanuš Wihan introduced the Sonata in Nuremberg on 8 December 1883, while also actively championing the Romanze as the soloist in the cello part. Headed Andante cantabile, this single-movement Romanze is one of the most mature works from Strauss’s early years as a composer. The solo cello enters after barely two bars, launching a disarmingly beautiful songlike line in whose lovely inwardness youthful emo- tions find instant expression. The calm writing for the cello and the simplicity of the mel- ody – still far removed from the refinements of the later composer – impress the listener with their elemental accessibility. Not even the exuberant climaxes and virtuoso passages can disrupt the cantabile tension of the arching melodic lines that place their distinctive stamp on the piece. For long stretches of the work, the accompaniment is notable for its chamber-like textures, ensuring that the cello part dominates the musical argument, and yet its subtle harmonic and instrumental colours provide the Romanze with an extremely interesting and highly effective framework. Robert Schumann: Cello Concerto in A Minor, op. 129 Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A Minor, op. 129 is widely regarded as the first Roman- tic cello concerto of overwhelming significance. Schumann wrote it in 1850 on taking up his new post as municipal director of music in Düsseldorf. His initial concerts in the town were enthusiastically received by local audiences, and this reception helped to inspire him as a composer. That same year also witnessed the composition of his Third Symphony (“Rhen- ish”) and, within barely two weeks in October, his Concertstück for cello and orchestra. But the latter work does not appear to have been performed in the Rhineland at this time, and it was not until 23 April 1860 that it received its first public performance in Oldenburg, when the soloist was Ludwig Ebert and the Grand Ducal Court Orchestra was conducted by its concertmaster Karl Franzen. There are a number of reasons for this delay. The first point to note is that Schumann, who had learnt to play the cello in his youth, struck out in this work in a direction little calculated to court popularity, ensuring that both publishers and performers maintained a sceptical distance. In 1851, the violoncellist of the Düsseldorf Orchestra, Christian Reimers, played through the solo part for Schumann, prompting him to approach the famous Frankfurt-based violoncellist Robert Emil Bockmühl and ask him for his expert guidance. He even invited Bockmühl to give the work’s first performance and Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin (RSB)

- 6. Robert Schumann: “Widmung” from the song cycle Myrthen, op. 25 Schumann’s song cycle Myrthen contains twenty-six songs, the first of which is a setting of Friedrich Rückert’s “Widmung” (Dedication) that inspired Liszt to write a dramatic and virtuosic transcription for piano solo. The cycle as a whole was a wedding present for Clara. Clara Wieck-Schumann: Romanze from the Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 7 This is Clara Wieck-Schumann’s only orchestral composition. She was still only fourteen when she composed a single-movement Concertsatz that Schumann helped her to instru- ment. Two further movements were added over the next two years, with the original con- cert piece now being added as the final movement, with the result that Clara was able to give the first performance of the finished work in the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 9 November 1835. The conductor was Felix Mendelssohn. The middle movement, headed Romanze: Andante non troppo con grazia, includes solo writing for piano and cello – a novelty in the concert literature of the time. The duet between these two instruments resembles a con- versation between two lovers. Johannes Brahms: Hungarian Dance no. 5 Brahms’s twenty-one Hungarian Dances were originally scored for piano four hands. The fifth is arguably the most popular and liveliest of the whole set. Brahms himself orches- trated only three of these dances, although it is in their orchestral versions that these pieces are nowadays known all over the world. In keeping with the Romantic tradition of his day, the famous Italian violoncellist Alfredo Piatti (1822–1901) arranged them for cello and piano, transforming them into examples of thrilling virtuosity. Dr. Wolfgang Horlbeck Translation: texthouse

- 7. Violoncello und Romantik Violoncello und Romantik werden heute in einem Atemzug genannt, das Cello gar als das romantischste Instrument schlechthin. Dies mag die Nähe des warmen Celloklangs zur menschlichen Stimme nahelegen, was in die Neigung der Romantik zu Poesie und kan- tablem Ausdruck passt. Hinzu kommt eine enorme Klangvielfalt über einen prachtvollen Tonumfang von nahezu fünf Oktaven, der in der Tiefe sonore Kraft, in der Mittellage eine reiche Ausdruckspalette und in den Geigenhöhen effektvolle Steigerungen ermöglicht. Diese edlen Vorzüge erklären eine kaum überschaubare Präsenz des Violoncellos in der romantischen Kammermusik. Erstaunlich ist, dass es dem Violoncello nicht gelang, sich im 19. Jh. als Konzertinstrument in den Vordergrund zu spielen – Klavier und Violine behaup- teten sich an der Spitze der Popularität. So sind es bis ins heutige Musikleben hinein nur wenige Cellokonzerte, die das 19. Jh. überstrahlen. Zu Unrecht jedoch sind eine ganze Reihe ebenbürtiger Werke unbeachtet geblieben und fast in Vergessenheit geraten. Es ist dem Engagement von Raphaela Gromes zu verdanken, die bereits auf ihren bisher bei Sony Classical erschienenen Alben spannende Neuentdeckungen präsentierte, so auch das dritte Violoncellokonzert von Julius Klengel, das bei Boosey & Hawkes herausgegeben wurde und nun auf diesem Album als Weltersteinspielung vorliegt. Julius Klengel: Violoncellokonzert Nr. 3 a-Moll op. 31 Weltersteinspielung Der Cellist und Komponist Julius Klengel (1859–1933), einer weit verzweigten Musikerfami- lie entstammend, war in seiner Zeit eine bedeutende Persönlichkeit des Leipziger Musik- lebens. Mit 15 Jahren spielte er bereits im Gewandhausorchester, ab 16 konzertierte er als gefeierter Wundercellist in Deutschland, mit 22 Jahren wurde er 1. Ensemblecellist und Mitglied im berühmten Gewandhausquartett. Bis 1924 gehörte er dem Gewandhaus- orchester an und erlebte das Wirken der großen Kapellmeister Carl Reinecke, Arthur Nikisch und für einige Jahre auch Wilhelm Furtwängler. Trotz seiner umfangreichen Verpflichtun- gen als Virtuose und geachteter Professor am Leipziger Konservatorium – gerühmt als „europäischer Cellistenmacher“ – hinterließ er auch ein beachtliches kompositorisches Œuvre, das sich vornehmlich auf Werke für Violoncello erstreckte. Für das Ensemblespiel seiner Studenten schrieb er einige Stücke für mehrere Celli, darunter den bis heute belieb- ten Hymnus für zwölf Celli. An größeren Werken komponierte Klengel vier Cellokonzerte, Doppelkonzerte für zwei Celli und für Violine und Cello sowie eine Serenade für Streich- orchester. Das 3. Violoncellokonzert op. 31 blieb lange Zeit unerklärlicherweise unbeachtet, bis es Raphaela Gromes vor kurzem aus seinem Dornröschenschlaf erweckte. Ursprüng- lich gelangte dieses Werk im 13. Abonnementkonzert des Gewandhausorchesters am 21. Januar 1892 zur Uraufführung. Julius Klengel spielte unter der Leitung von Gewand- hausdirigent Carl Reinecke den Solopart selbst. „Der Beifall war ein äußerst stürmischer, dem mehrere Hurrarufe folgten“, berichtete damals Rezensent G. Schlemüller im Leipziger Anzeiger. Weiter schrieb er, dass „die Composition […] als eine wirkliche Bereicherung der einschlägigen Literatur zu betrachten“ sei, weil sie sich „überall von Trivialitäten fernhält und in der Cantilene sowohl im Passagenwerk eigenartig ist“. Auch in der von Robert Schu- mann 1834 gegründeten „Neuen Zeitschrift für Musik“ Nr. 4 vom 27. Januar 1892 erschien eine Kritik: „Das Cello-Konzert gliedert sich in drei Sätze: Allegro non troppo, Intermezzo- Allegretto und Finale-Vivace. Dieselben stehen aber nicht vereinzelt da, schließen nicht für sich ab, wie es bei den meisten früheren Concerten geschieht, sondern sind modu- latorisch, organisch miteinander zu einem Ganzen verbunden. Auch der Inhalt ist nicht nach gewöhnlicher Schablone gearbeitet. Schwierige Passagen wechseln mit getragenen Cantilenen ab. Einige Trompetenfanfaren schienen zum Turnier oder Kampf aufzufordern. Jedoch endigte Alles friedlich und der Virtuose und Componist in einer Person wurde mit reichlichem Beifall und Hervorruf geehrt.“ Heute ist dieses Werk – seine virtuose Eleganz verrät die Handschrift des berufenen Cello- Praktikers – eine echte Bereicherung der romantischen Celloliteratur. Der 1. Satz Allegro non troppo beginnt nahezu modellhaft: In einer Einleitung stellen Celli und Fagott im Halb- dunkel der tiefen Lage die Motive des Hauptthemas vor. Das Solocello setzt präludierend ein, ehe es das schöne liedhafte Thema exponiert. Die virtuose Fortspinnung führt zum nun aufwärts führenden, ebenso sanglichen, nur sparsam begleiteten Seitenthema. Nach wiederum virtuosem Solo beschließt das Orchester mit großer jubelnder Geste diesen Teil, dem sich überraschend weder Durchführung noch Reprise anschließen. Ein eher lyrischer Kommentar des Cellos wirkt wie eine Hinführung zum 2. Satz Allegretto. Dieser Satz ent- faltet sich als dreiteiliges Scherzo-Intermezzo, die von Schucht erwähnten „Trompeten- fanfaren“ werden vom Cellopart fröhlich kommentiert. Der triolische Grundrhythmus lässt gar das Flair eines graziösen Walzers aufkommen, ehe eine große Kadenz, die wehmütige Motivik des Kopfsatzes aufgreifend, zum Abschluss führt. Der 3. Satz Allegro vivace lässt sogleich ein temperamentvolles, ungarisch anmutendes Thema in den Mittelpunkt sprin- gen, das vom Solo spielerisch-lustvoll ausgeziert wird. Auch das Orchester präsentiert ein tänzerisches Thema, gut an dem abwärtsführenden Tonleitermotiv erkennbar. Nach einer Reminiszenz an das Seitenthema des Kopfsatzes beschließt eine Coda mit dem Tutti- Thema das Werk. Richard Strauss: Romanze F-Dur o. Op. 75 / TrV 118 Diese Romanze ist Teil des reichen Jugendwerks Richard Strauss‘, in dem sich der kaum 19-Jährige kompositorisch nicht nur in den verschiedenen Gattungen und Instrumenten ausprobierte, sondern auch erste Markenzeichen seiner genialen Begabung setzte. Dazu gehören sein Violinkonzert, zwei Sinfonien, bis heute ungemein populär die 13-stimmige Bläserserenade und das erste Hornkonzert, das der 18-Jährige dem Vater zum 60. Geburts- tag schenkte. In jener Zeit ist auffällig, dass viele Werke aus den Beziehungen des jungen Strauss‘ mit wichtigen Persönlichkeiten aus seinem Umfeld heraus entstehen. Dazu zählt auch seine am 17. Juni 1883 vollendete Romanze in F-Dur für Violoncello und Orchester. Für die bereits erstaunliche Stilsicherheit im Umgang mit dem Violoncello trug wesentlich der enge Kontakt zu dem berühmten Solocellisten des Kgl. Hoforchesters München, Hanuš

- 8. Wihan, bei. Ihm, dem „lieben Freunde“, hatte der 16-jährige Richard Strauss bereits die Cel- losonate op. 6 (TrV 115) gewidmet, deren Urfassung aus den Jahren 1880/81 er gründlich revidierte und kurz vor Vollendung seiner Cello-Romanze dem Druck beim Wiener Verlag Josef Aibl zuführte. Raphaela Gromes und Julian Riem präsentierten die Urfassung in einer Weltersteinspielung zu Beginn 2020. Hanuš Wihan brachte die Sonate Ende 1883 in Nürn- berg zur Uraufführung und setzte sich auch – als Solist des Celloparts – nachdrücklich für das Bekanntwerden der Romanze ein. Das einsätzige Werk, versehen mit der Tempoangabe Andante cantabile, ist eines der reifsten Werke jener Strauss’schen Jugendzeit. Das nach kaum zwei Takten einsetzende Solocello beginnt mit einem entwaffnend schönen ‚Gesang‘, in dessen liebevoller Innigkeit jugendliche Emotionen unvermittelt Ausdruck finden. Die ruhige Führung der Cellostimme und die Schlichtheit der Melodie – noch weit entfernt von den Finessen des späteren Meis- ters – beeindrucken durch ihren elementaren Zugang, selbst die temperamentvollen Stei- gerungen und virtuosen Passagen durchbrechen nicht die kantable Spannung der großen Melodiebögen, die dem Werk ihre Faktur geben. Die in weiten Teilen kammermusikalisch wirkende Orchesterbegleitung weist dem Cellopart stets das Primat des musikalischen Geschehens zu, gibt der Romanze dennoch mit ihrer feinen harmonischen und instrumen- talen Koloristik einen überaus interessanten und wirkungsvollen Rahmen. Robert Schumann: Violoncellokonzert a-Moll op. 129 Das Violoncellokonzert a-Moll op. 129 von Robert Schumann gilt als das erste überragende Cellokonzert der Romantik. Schumann komponierte es im Jahre 1850, als er sein Amt als Städtischer Musikdirektor in Düsseldorf antrat. Die ersten Konzerte Robert Schumanns wurden von den Rheinländern begeistert aufgenommen, was ihn auch in seiner kompo- sitorischen Arbeit beflügelte. Es entstehen noch in diesem Jahr seine 3. Sinfonie „Rheini- sche“ und innerhalb von kaum zwei Oktoberwochen sein „Concertstück für Violoncello mit Begleitung des Orchesters“. Eine Uraufführung kam im Rheinland offenbar nicht zustande. Seine erste öffentliche Präsentation ist erst am 23. April 1860 in Oldenburg durch die Groß- herzogliche Hofkapelle unter Leitung ihres Konzertmeisters Karl Franzen und dem Solisten Ludwig Ebert belegt. Es gibt einige Gründe für diese Verzögerung. Zunächst ist zu würdi- gen, dass sich Schumann – er hatte in früher Jugend das Cellospiel erlernt – mit diesem Konzert in damals noch wenig populäre kompositorische Welten wagte, was Verleger wie Interpreten auf skeptischer Distanz hielten. Nachdem ihm 1851 der Cellist des Düsseldor- fer Orchesters, Christian Reimers, den Cellopart probeweise vorspielte, ersuchte er den in Frankfurt bekannten Cellisten Robert Emil Bockmühl um fachliche Unterstützung, bot ihm die Uraufführung des Konzertes an und betraute ihn mit der spieltechnischen Ausfertigung der Stimme. Die Hoffnung, mit ihm eine Düsseldorfer Aufführung bestreiten zu können, erfüllte sich nicht: Bockmühl fand immer neue Ausflüchte, um der Aufführung des Werkes aus dem Weg zu gehen. Mit Bedacht nannte Schumann sein Werk zunächst „Konzertstück“, denn dieses ‚Konzert’ entspricht seiner formalen Auffassung, „wie das Orchester [mit dem Soloinstrument] zu Nicholas Carter

- 9. verbinden sei“, eigentlich nicht: In den ersten beiden Sätzen agiert das Violoncello als Soloinstrument dominant, ist durch und durch virtuos, verweigert dem Kopfsatz gar eine Orchesterexposition, drängt das Orchester im 2. Satz auf eine sparsame Begleitung zurück. Und dennoch ist dieses Werk keines der üblichen Virtuosenkonzerte – da es das virtuose Moment dem vom Melodiefluss getragenen Ausdruck unterordnet, sodass es auf seine Art noch heute aus dem überschaubaren Repertoire der Cellokonzerte weit herausragt. Der Form nach hat das Cellokonzert eine dreisätzige Struktur, verschmilzt jedoch durch flie- ßende Übergänge das in allen Sätzen vielfältig genutzte thematische Material und das inte- grierende Durchführungsprinzip zur Einsätzigkeit. Die poetische Atmosphäre überstrahlt das Gesamtwerk wie ein Bogen. Zu Beginn des 1. Satzes Nicht zu schnell übernimmt das Violoncello nach einer kurzen Orchesterkadenz die Präsentation des elegischen, fast 30 Takte langen Hauptthemas. Das nachfolgende Orchestertutti greift wohl Segmente dieses Themas auf, eröffnet hier aber bereits einen permanenten durchführungsartigen Prozess, der sich mit dem reichen motivischen Material nahezu improvisatorisch auseinandersetzt. Anstelle der üblichen Solokadenz überrascht im Abschluss dieses Satzes eine zärtliche Cellokantilene, die zugleich in den 2. Satz Langsam – Etwas lebhafter – Tempo I – Schnel- ler überleitet. Ein inniges Thema entfaltet in vielfältiger Verarbeitung seinen ganzen emo- tionalen Reiz, den dynamischen Ecksätzen Ruhe und Ausgewogenheit entgegenstellend. Die Pizzicato-Begleitung der Streicher, auch das Hinzutreten einer zweiten Cellostimme zum Solopart, unterstreicht den kantablen Charakter dieses Intermezzos. Der sich mit einer Solopassage anschließende 3. Satz Sehr lebhaft – Im Tempo – Schneller hat eine rondoartige Struktur, geprägt durch ein kerniges Kopfmotiv, das selbst den episodenhaf- ten Zwischenspielen Gestalt gibt. Solo und Orchester sind in diesem Satz gleichgewichtig miteinander verflochten. Bei der vorliegenden Aufnahme mit dem Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin setzt sich Raphaela Gromes gemeinsam mit dem jungen australischen Dirigenten Nicholas Carter für eine transparente und kammermusikalische Interpretation des Werkes ein. Zugaben Das Erfolgsduo Raphaela Gromes und Julian Riem bereichert gegenwärtig den Fundus der romantischen Kammermusik mit immer neuen Ideen und Arrangements, wie es die Zugaben auf diesem Album anklingen lassen: Kompositionen der „romantischen Titanen“ Schumann und Brahms sowie der hochbegabten Clara Wieck, der späteren Ehefrau von Robert Schumann und engen Freundin von Johannes Brahms. Robert Schumann: „Widmung“ aus dem Liederzyklus Myrthen op. 25 Das Auftaktlied „Widmung“ (Friedrich Rückert) zu Schumanns 26-teiligem Liederzyklus „Myrthen“ – das Hochzeitsgeschenk für Clara Wieck – riss bereits Franz Liszt zu einer dra- matisch-virtuosen Klavierbearbeitung hin. Raphaela Gromes & Julian Riem

- 10. Clara Wieck-Schumann: Romanze aus dem Klavierkonzert a-Moll op. 7 Dieses Werk ist Clara Wieck-Schumanns einzige Komposition für Orchester. Mit 14 bereits hatte sie ein einsätziges Konzertstück fertiggestellt, das ihr Robert Schumann instrumen- tieren half. In den folgenden zwei Jahren kamen zwei weitere Sätze hinzu, sodass sie am 9. November 1835 ihre nun komplette Arbeit – das ursprüngliche Konzertstück wurde zum Finalsatz – im Leipziger Gewandhaus unter der Leitung von Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy zur Uraufführung bringen konnte. Der Mittelsatz Romanze: Andante non troppo con grazia ist – ein Novum in der Konzertliteratur – zwei Solopartien an Klavier und Violoncello vorbe- halten. Das Duett dieser beiden Instrumente gleicht einem liebevollen Zwiegespräch. Johannes Brahms: Ungarischer Tanz Nr. 5 Der fünfte der 21 „Ungarischen Tänze“ – Johannes Brahms schrieb sie im Original für Klavier vierhändig – ist wohl der beliebteste Temperamentsbolzen des gesamten Zyklus. Nur drei der Tänze – sie sind heute weltweit in ihren Orchesterfassungen bekannt – hat Brahms selbst instrumentiert. Der berühmte italienische Cellist Alfredo Piatti (1822–1901) arran- gierte die Ungarischen Tänze – der romantischen Tradition folgend – zu hinreißenden Vir- tuosenstücken für Cello und Klavier. Dr. Wolfgang Horlbeck

- 11. G010003941607E