IT Educational Policies Boost National Competitiveness

- 1. Department of Economics University of Warwick EC331: Research in Applied Economics April 2015 How can ‘IT’ improve National Competitiveness? Student ID: 1203596 Research Supervisor: Dr. Piotr Jelonek1 Word Count: 4985 Abstract The rise of Information and Technology (‘IT’) over recent decades has become to be considered a defining characteristic of the age we live in. This paper is targeted towards policymakers who identify IT related strategies as a tool to improve national competitiveness. A novel and objective framework for optimally measuring the multi-dimensional concept of national competitiveness is first developed. Through the estimation of a Dynamic Panel Data model, the paper then provides evidence that policymakers should focus their efforts towards IT educational policies. These educational policies should take priority over and above policies targeting a country’s national IT communication infrastructure and the diffusion of IT throughout an economy. It is argued that IT educational policy reforms will significantly and sustainably boost a country’s national competitiveness. 1 The author is grateful to Dr. Piotr Jelonek for his support and guidance throughout the project and particularly in the development of the measure of national competitiveness derived in this paper. Any errors remain the author’s own.

- 2. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 2 Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction 3 Section 2 Literature Review 4 2.1 What is National Competitiveness? 4 2.2 IT & National Competitiveness 4 Section 3 Data & Methodology 6 3.1 Data Overview 6 3.2 Measuring National Competitiveness 6 3.3 IT Variables & Research Hypotheses 8 3.4 Model Specification 9 Section 4 Results 10 4.1 Choice of Dependent Variable 10 4.2 Empirical Estimations 11 Section 5 Discussion 12 Section 6 Conclusions 13 6.1 Conclusions & Policy Recommendations 13 6.2 Limitations & Directions for Further Research 14 Appendices 16 Appendix A 16 Appendix B 19 Appendix C 21 Bibliography 24

- 3. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 3 1. Introduction The object of this thesis is to identify the most effective direction for Information & Technology (‘IT’) related policies to take, in order to improve a typical country’s national competitiveness. Policymakers across the world are increasingly considering the use of IT as a key tool to achieve policy objectives due to the abundance of opportunities which it presents (e.g. European Commission, 2004). The development of IT has driven a revolution in the modern world, with ever improving technology rapidly changing our consumption, investment and behavioural patterns. IT now concerns a broader spectrum than the desktop computers which simply performed repetitive calculations when first introduced. This evolution and has prompted new industries, such as the smart mobile phone and tablet markets, as well as the development of software applications which they use. Moreover the majority of pre-existing industries in the modern economy are now shaped to some extent by IT. The improvements in speed and effectiveness of communication methods is often at the heart of this influence, particularly for developed nations of knowledge-based economies. The influence of IT throughout our everyday lives is clearly evident and current trends suggest that the use of IT is only likely to increase in the future. As the world moves through the iterative development of newer, faster and better technologies, educational policy has started to adapt to accommodate these patterns. IT has given rise to a body of topics within its own right. Additionally schools use the products of IT to enhance learning in other disciplines. The internet is perhaps the best example to give, as this allows for research in an abundant library of knowledge. This broader effect of IT shows the potential of the knock-on effects that technologies may develop, further evidencing the use of IT beyond its own borders. The ease of communication is considered to be one of the key triggers of modern globalization, which in turn has led policymakers to consider the national competitiveness of countries. This abstract concept that has emerged offers many perspectives which form the topic matter of Section 2.1 below. In the context of this thesis, national competitiveness is defined as the ability of a nation to compete within itself and with other nations in global markets. The complex and multidimensional nature of national competitiveness results in a non-trivial answer to the title of this thesis. After deriving a measure of national competitiveness in line with the above definition, three hypotheses are tested pertaining to the effects of IT communication infrastructure, the diffusion of IT and of IT educational policy. The empirical findings of this thesis suggest that IT related educational polices have a significant and positive impact on national competitiveness. It is thus argued that policymakers intending to focus on the development of IT in an economy need to direct efforts towards the upskilling of its labour force through effective educational reform policies. Section 2 presents a review of the relevant literature, briefly reviewing the concept of national competitiveness before detailing the current understanding of the impact of IT. Section 3 outlines the data and the methodology used in the formulation of the proposed measure of national competitiveness and the dynamic panel model which is employed to test the research hypotheses. Section 4 reports the empirical findings of the analysis which are thoroughly discussed in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 offers conclusions of the thesis and suggest possibilities for further research.

- 4. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 4 2. Literature Review 2.1 What is National Competitiveness? The intricate nature of national competitiveness has resulted in an array of differing approaches used by researchers and institutions. In this subsection, some of the key contributions necessary to gain an understanding for the context of this thesis are discussed. Porter (1990) argues that several individual approaches to competitiveness contain ‘some degree of truth’ but fail to achieve a general approval among academics. For example, the availability of cheap labour in order to ‘compete’ in global markets, the availability of natural resources, ‘competitive’ exchange rates and the view that government policy is the key driver of national competitiveness all provide some insight in a given context, but fail in others. Through his Diamond Model, Porter proposed that productivity was the key underlying factor in evaluating national competitiveness. Delgado et al (2012) present a comprehensive review of the development of national competitiveness, suggesting that the debate centres around three core themes: costs, market share and productivity. The researchers proceed to derive a complex measure of national competitiveness stemming from what they define as ‘foundational competitiveness,’ a microeconomic measure of productivity. Mittal et al (2013) frame three dimensions of competitiveness: (i) at the firm or company level, (ii) at the sector or industry level, and (iii) at the national level. This framework is appealing, although due to the interconnected nature of the three dimensions, these distinctions provide minimal structure to shape our understanding. Momaya (2008) provides one such example of this, highlighting interplay between industry and national levels. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Reports (‘GCRs’) and the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook each use a holistic approach to national competitiveness, but there are differences between each. In the most recent GCR, national competitiveness is defined as the ‘set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of production of a country’. This far reaching definition covers many concepts and indicators. Neither however consider causal relationships, but construct their own competitive indices based on a vast volume of information and factors. National Competitiveness is increasingly being viewed as a dynamic concept. Kharlamova and Vertelieva (2013) stress that the competitiveness of today will affect the competitiveness of tomorrow. This logic is convincing, therefore it is important that future research on national competitiveness employs time dependent models to at allow for this possibility. 2.2 IT & National Competitiveness Numerous studies have directly and indirectly linked the impact of IT to competitiveness. Kumar and Charles (2009), for example, identify technological change as the causal force of productivity improvements in the modern economy, which under Porter’s approach would equate to national competitiveness. Furthermore within the GCR, Technological Readiness is one of the 12 pillars of competitiveness assessed. Löfgren (2008) argues a multidimensional approach is needed to assess the effect of IT on an economy to account for its far reaching direct and indirect influences.

- 5. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 5 In parallel to the rise of IT in the modern world has been the development of the knowledge economy, which has influenced a large body of literature. Chen & Dahlman (2004) assess the contribution of knowledge to growth. Among other findings, IT infrastructure is identified as an important channel for communication, with the researchers reporting a 0.11 percentage point increase in economic growth caused by a 20% increase of the number of phones per 1000 people in the population. There is a rich body of literature which concerns the diffusion of IT and the benefits which it can bring to national competitiveness, particularly for developing nations. Kubielas and Olender-Skorek (2014) for example presents evidence that Central Eastern European countries have greatly benefited from this rapid technology transfer. Further attention however has been paid to the absorptive capacity of a nation, on the logic that a nation must be well positioned in order to take advantage of these technology transfers. Dahlman & Brimble (1990) talk about National Absorptive Capacity. Similarly, Cohen & Levinthal (1989, 1990) stress some importance of an absorptive capacity. Mowery and Oxley (1995) assess the contributions of IT to Total Factor Productivity Growth (TFP) and conclude that there are enabling conditions necessary for the effective transfer of technology, pointing directly to the need for adequate human capital. Achieving a sufficiently educated labour force to meet the demand for modern-day jobs is not as simple as it would first seem. The problem is due to the rapid development rates of IT which means that ‘the hardware doesn’t yet exist, the software hasn’t yet been written, and some of the key companies don’t yet exist,’ (Yapp, 2001 in Riley 2004). Riley (2004) proposes reforms to the education system in line with many other researchers that schools need to teach problem solving skills and facilitate creative thinking in the classroom in order to allow the next generation entering the labour force to meet the demand for new (at this point unknown) jobs and therefore encourage a competitive economy. With regards to addressing which IT related factors are of the greatest importance, there is some debate in the literature. Zamora-Torres (2014) performs principal component analysis on a set of thirteen indicators sourced from the World Bank in 2012. He shows that the factors of (i) ‘High development of technology and innovation’ (including exports of high technology products and patent applications) and (ii) ‘Global investment in innovation and development’ (including spending on R&D as a percentage of GDP) have the greatest impact towards being technologically competitive. This paper contributes to the literature by testing three distinct IT related factors against national competitiveness, which allows for the inclusion of the indirect effects of IT throughout the economy to be considered.

- 6. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 6 3. Data & Methodology 3.1 Data Overview The model developed in this thesis uses data from the World Economic Forum’s GCR which is published annually. A panel of 116 countries over 8 waves from 2006 to 2013 inclusive, with the selection of the countries determined by availability of the data below in the vast majority of waves.2 Where data is not available, it is for a variety of reasons, but these can include war and natural disaster which hinder efforts to gather the required information. This in itself poses an initial problem as these countries are typically characterized among the least competitive of nations, which implies downward bias for the reporting of the results. Alternatively, the sample may be considered representative of countries who are in a position to address economic policy objectives, due to the stability of their country. The GCR provides a rich and comprehensive dataset which is ideal for the analysis of national competitiveness, including a range of microeconomic and macroeconomic factors that makes it ideal for national competitiveness research. The dataset also includes the World Economic Forum’s own Global Competitiveness Index (‘GCI’) which is constructed from the data its analysts gather and then used to rank countries by competitiveness. These rankings are based on what the GCR terms the ‘12 Pillars of Competitiveness,’ and are outlined in Appendix C. This thesis also uses GDP and export data from the World Bank and IMF databanks, in both absolute levels and annual percentage increase. GDP data in absolute levels is expressed in 2005 USD and exports are given in volumes indexed to 100 in the base year 2000. 3.2 Measuring National Competitiveness3 Existing measures on National Competitiveness may be divided between those focusing on an intra- national competitiveness, that is the competition within a nation, and an inter-national competitiveness, the competition between nations. The former is particularly true for larger nations, such as the US. It is noted however that the two may not be mutually exclusive, as it is difficult to be inter-nationally competitive without being intra-nationally competitive, and similarly for the converse. Any indicator of competitiveness will align better to one of these perspectives and will critically shape the direction the researcher’s analysis. To address this divide, the national competitiveness of a given country i in year t is expressed as a general function its intra-national and inter-national competitiveness: , , ,( , )Intra Inter i t i t i tNC f NC NC (1) To proxy for each of these factors, GDP and exports are considered respectively, and expressed a simple linear functional form of a weighted average of the two, which are normalized to the unit interval, as detailed in Equation (2). Each proxy aligns well with the theoretical motivation. GDP measures will favour intra-national competitiveness, but may also be sensitive to the inter-national 2 A complete list of these countries and further note son the data can be found in Appendix A. 3 Supporting notes on this methodology can be found in Appendix B.

- 7. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 7 competitiveness of a nation. Similarly, export measures will better reflect an inter-national competitiveness, but also will be influenced by a nation’s intra-national competitiveness. , , ,(1 )i t i t i tNC Y X (2) Where ,i tY represents the GDP of country i in year t, normalized to [0,1] ,i tX represents the exports of country i in year t, normalized to [0,1] 0,1 is the weight of GDP Given this functional form, two key questions emerge. Firstly, what value should the weight take? To answer this, a framework is developed whereby the rankings produced by the GCI are compared to rankings of nations produced by ranking the construct of national competitiveness. The problem is set to minimize the square difference in ranking after summing over all countries in all waves, as detailed in Equation (3). The GCI is chosen as reference point as a good collective understanding of what it means to be nationally competitive. 2 , , [0,1] 1 1 arg min T N i t i t t i GCI NC (3) Where ,i tGCI is the in sample ranking of country i in the start year t of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitive Index. ,i tNC is the ranking of country i in year t for a given weight computed by equation (2) . N is the number of countries in sample, equal to 116. T is the number of waves in sample, equal to 8. The second question that arises is what units of measurement should be use to express GDP and exports? Equation (3) is analysed through four cases of GDP and export data outlined in Table 1 below, which also outlines the motivation for each. The weight and the optimal combination of units of measurement above is then chosen to compute the measure of national competitiveness of country, using Equation (2). Whilst no case appears to be clearly favourable to another, it is considered that Case 3 offers most promise as it provides a logical middle ground between Case 1 and Case 2. This case may therefore be most suited to a general measure of national competitiveness.

- 8. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 8 Table 1: Combinations of GDP and exports expressed in levels or annual percentage change Case GDP Unit Measure Export Unit Measure Motivation 1 Annual Percentage Change Annual Percentage Change Percentage changes may better reflect the competitiveness of a given year. Smaller and developing countries are not penalized by these factors. Consistency in measure of Percentage change. 2 Absolute Value expressed in 2005 USD Volume, with index to year 2000 for baseline score of 100 Developed countries may have low growth rates but still be considered competitive. Consistency in measure of levels. 3 Absolute Value expressed in 2005 USD Annual Percentage Change Competitive nations characterised by high intra-national competitiveness and inter- national competitiveness may both favour each unit respectively. 4 Annual Percentage Change Index volume (2000=100) Completeness of analysis. 3.3 IT variables Three variables are constructed to distinguish the contributions of IT on national competitiveness, which are described in Table 2 below. Each is constructed of an equally weighted average of the original variables reported in the GCRs, so the newly constructed variables follow the same measurement units also. It is worth noting here that the Quality of Maths & Science Education is preferred to a measure of IT teaching. This is in line with Riley (2004) who argues that due to technological innovation, the jobs of the future are unknown and uncertain. It is therefore necessary to consider the mathematical and scientific educational policy as these subjects give the transferable skills and ideal background for software and hardware engineering. The internet access in schools component may be viewed from two angles: the potential use of IT to aid in learning in other subject areas and the teaching a basic computer skills. The use of the internet in schools thus implies a basic understanding of computing knowledge. The involvement of IT communication infrastructure provides the basis for the knowledge economy, as discussed in Chen and Dahlman (2004) and the IT diffusion measure is reflective of approaches taken in Mowery and Oxley (1995) and Nelson (1990).

- 9. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 9 Table 2: Construction of IT related variables Variable Name Description Original Variables from GCR Units of Measurement ITcom IT communication infrastructure in a nation Mobile Phone Subscriptions Per 100 individuals Fixed Broadband Subscriptions Per 100 individuals Individuals using the Internet Per 100 individuals ITdiff Factors affecting the diffusion of IT in a nation’s economy Availability of Latest Technology Normalized Scale: 1-7 Firm Level Technology Absorption Normalized Scale: 1-7 FDI & Technology Transfer Normalized Scale: 1-7 ITeduc Ability of the nation to produce a labour force with appropriate IT skills Quality of Maths & Science Education Normalized Scale: 1-7 Internet Access in Schools Normalized Scale: 1-7 Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed: Hypothesis 1 IT communication infrastructure has a significant effect on national competitiveness. Hypothesis 2 The diffusion of IT has a significant effect on national competitiveness. Hypothesis 3 IT educational policies have a significant effect on national competitiveness. It is expected that all will have positive and significant effects, but no expectations are attributed to the relative magnitude of the coefficient estimates. 3.4 Model Specification Based on the above national competitiveness and IT variable derivations, an Arellano-Bond two-step dynamic panel data (‘DPD’) model is specified by the Generalised Method of Moments (GMM): 11 , 1 , 1 1 , 2 , 3 , , 1 i t i t i t i t i t j j i t j NC NC ITcom ITdiff ITeduc X (4) Where ,i tNC Is the national competitiveness of country i in wave t

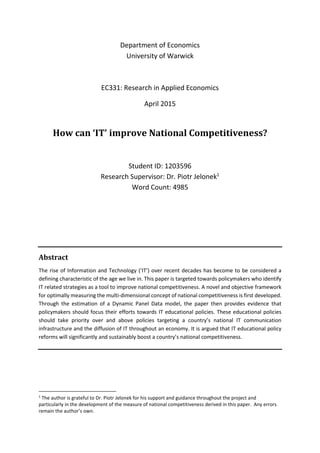

- 10. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 10 , 1i tNC Is the lagged national competitiveness of country i in wave t ,i tITcom ,i tITdiff ,tiITeduc Are the three IT related variable of interest, as defined in Table 2 jX Is a vector of controls comprising of the GCR Pillars of Competitiveness4 Each control is reported for country i in wave t ,i t Is the error term All variables are given in first differences, as denoted by , (Arellano and Bond, 1991). 4. Results 4.1 Choice of Dependent Variable Figure 1 below shows the results of the four cases for determining the optimal weight and measure of GDP and exports in order to construct the dependent variable of national competitiveness. 4 The ninth pillar of Technological Readiness has been excluded due to its similarity with the ITflow variable of interest. 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 Sumofsquredifferenceinranking, Overallcountriesandwaves, Millions Weighting, ω Figure 1: Effectiveness of the constructed NC variables As specified in Equation (3), by measurement unit comibations in Table 1 Case 1: GDP in % change & Exports in % change Case 2: GDP in 2005 USD & Exports in volumes Case 3: GDP in 2005 USD & Exports in % change Case 4: GDP in % change & Exports in volumes

- 11. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 11 Each point on each line represents a unique measure of national competitiveness. Computations are made for incremental magnitudes of 0.01 for omega within the unit interval, giving a total of 400 measures of national competitiveness that are considered in this figure. Each measure is thus characterized by the combination of: (i) the weighting of omega (depicted on the abscissa); (ii) the unit measure of GDP (depicted in the case combinations); and, (iii) the unit measure of exports (depicted in the case combinations). As the function f(omega) is to be minimized, the lower the score on the ordinate axis, the lower the difference between the newly constructed ranking and the ranking determined by the GCI, and therefore the more effective the combination is for a measure of national competitiveness. The minimum point is identified at 1 , showing that the GDP expressed in levels (2005 USD) outperforms all other combinations. Given this result, national competitiveness is expressed in line with Equation (5) which reduces to Equation (6) for use in Section 4.2 below. 2005 2005 % , , , ,, (1) (0) (1) (0)USD Vol USD i t i t i t i ti tNC Y X Y X (5) 2005 ,, USD i ti tNC Y (6) 4.2 Empirical Estimations Equation (7) reports the key results of the Arellano-Bond DPD model. Robust standard errors, adjusted for clustering by country, are given in parentheses. 11 , , 1 , , , , 1 ˆ0.4228 0.0005 0.0038 0.0299 (0.1330) (0.0032) (0.0078) (0.0122) i t i t i t i t i t j j i t j NC NC ITcom ITflow ITeduc X (7) The results of the model give evidence which supports the third hypothesis that IT education policy significantly impacts on national competitiveness, which is significant at the 5% level (p=0.014). Conversely, both the first and second hypothesis, the use of IT in communication and that the diffusion of IT significantly impact national competitiveness, are not supported (p=0.627 and p=0.871 respectively). Eight of the eleven controls are also shown to be significant. These results will be discussed extensively in Section 5 below.5 5 See Appendix C for the full empirical estimations.

- 12. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 12 5. Discussion Given the lack of a consensus on the approaches to national competitiveness, the choice of dependent variable is fundamental to research undertaken in this field. By construction of a new index for national competitiveness a simple measure of the multi-dimensional concept has been developed. The use of the Global Competitiveness Report’s rankings as a benchmark for comparison allows one to make use of this rich understanding to develop an informed metric which is objectively defined. It is interesting to note the existence of a corner solution for each of the four combinations of measures of Figure 1, resulting in a strict preference ordering for the measures of GDP and exports considered in this thesis. From the most to least effective measure: 1. GDP in levels (2005 US Dollars), 2. Exports in annual percentage change. 3. Exports in levels (indexed to 2000 volumes) 4. GDP in annual percentage changes. This simplification is welcomed in what is often a complex and interconnecting field of study, however further investigation would be needed to confirm and validate this finding. It may for example occur as the result of the specific functional form employed in Section 3.2. Indeed, these results prompt the call for further research to investigate this methodology involving linear forms of higher degree polynomials. A second and critical assumption implicit in the above analysis is that GDP and exports are good proxies for intra-national and inter-national competitiveness respectively. The intuition behind is this is reasonable, however one may criticism may be that they alone are overly simplistic. This criticism could be levied against any single measure of competitiveness, as Porter (1990) observes. A critical contribution of the analysis is the novel methodology in selecting the most appropriate measure to use. It remains true that no single metric will fully encapsulate our broad and qualitative understanding of national competitiveness without being constructed from all explanatory variables – which of course makes it difficult to undertake causal analysis. Nevertheless, Figure 1 makes good progress in clarifying the understanding of approach taken in this thesis. Analysis of this approach is an important pretext for explaining the results of the three hypothesis. The inability to reject the null of the first hypothesis regarding the communication of IT is perhaps the most surprising, especially when contrasted with the results of Chen and Dahlman (2004). It is possible that the knowledge economy is only significant for the most economically developed nations, which could accommodate this result. The lack of evidence to support the second hypothesis regarding the diffusion of IT is contradictory to much of the existing literature, but it is argued that this may be reconciled alongside the importance of education which is supported through the empirical estimations. Access to new technology may lead to ambiguous effects on productivity depending on the skill of the labour force using it. On the one hand, if a new technology is known or understood by an individual then productivity is likely to improve. However, if a new technology is unknown or misunderstood by an individual, this will hinder productivity in the short term until such a time when the individual learns to use it effectively. It should

- 13. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 13 be note that the technology need only to be considered ‘new’ in the eyes of the individual who uses it, so this may apply to older technologies which are diffused throughout an economy as well. The apparent importance of educational policy is however consistent with previous research literature (Mowery and Oxley 1995, Dahlman and Brimble 1990, Cohen and Levinthal 1990). IT orientated education policies will have a direct impact on the labour force supplying the growing and increasingly diverse IT sector. In addition, the policies will have a broader effect of producing a technologically capable labour force to supply efficient workers to other industries throughout the economy. It is argued that IT educational policies should drive the development of the typical nation which attempts to improve its national competitiveness. Critically this should be prioritised over policies addressing the IT communication infrastructure or the diffusion of IT throughout an economy. For a policymaker intent on acting on this argument, Hargreaves and Goodson (2006) analyse the sustainability of educational reform, noting that changing economic conditions are one of the key drivers of sustainable educational development. However, the importance of a skills based approach over a syllabus of IT content must again be stressed. Therefore such IT orientated educational policies should be broad: the focus needs to be on the mathematical and scientific topics rather than purely computing. The integration of IT does however does bring potential for further engaging students, which is another important consideration for educational reforms (Sahlberg, 2006). This policy recommendation is consistent with Nelson (1992) who argues that national competitiveness is built upon scientists and engineers. This thesis extends this argument, focusing on the contributions that an education in mathematics and the sciences will produce the hardware and software engineers of tomorrow. The development of IT engineers will strongly contribute to national competitiveness and, all else being equal, will improve a nation’s national competitiveness. The use of the Arellano-Bond dynamic panel data model is vindicated through the evaluation of the lagged term value of national competitiveness. The coefficient is significant at the 1% level (p=0.001) which confirms the importance of allowing for the partial endogeneity of the dependent variable. The magnitude of the coefficient is far larger than any other (see Appendix C) which suggests that there are strong momentum effects of national competitiveness. Further research may be needed to validate this conclusion, if it is to be applied generally across all measures of the concept. 6. Conclusions 6.1 Conclusions & Policy Implications It is argued that any policymaker who aims to target the abstract concept of national competitiveness must consider a range of approaches and their respective findings, judging each on its own merits. In this thesis, national competitiveness is defined as a general function of a nations’ intra-national (‘within country’) and inter-national (‘between countries’) competitiveness. A simple proxy for each was constructed in GDP and exports respectively, with a proposed specific functional form expressed as a weighted average of the two.

- 14. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 14 The units of measurement for GDP and exports, alongside the weighting were determined objectively by benchmarking the rankings produced from the 400 combinations considered against the rankings of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report. The optimal measure of national competitiveness was found to be GDP expressed in 2005 USD (with the weight omega=1 eliminating the involvement of exports). Using this measure as the dependent variable, an Arellano-Bond DPD model estimated the impact of IT on national competitiveness. Estimations focused on three distinct channels: IT communication infrastructure, the diffusion of IT and IT educational efforts. The derivation of this national competitiveness measure forms a novel way to assess a complex and multidimensional concept, taking into account a rich volume of this information in a relatively simplistic manner. The optimization problem of Equation (3) crucially gives objectivity in determining the weighting and unit measurement of GDP and exports. Without this, the choice of omega is purely arbitrary, and intuition leads to multiple combinations of measurement units. In itself, the evaluation of this problem delivered interesting results contributing to our conceptual understanding of national competitiveness. However more importantly, it provided a solid basis on which to test hypotheses at the heart of this thesis. Through analysis of the three channels, the results support the importance of educational policies to give significant contributions to national competitiveness, in line with much of the existing literature (Mowery and Oxley 1995, Riley 2004, Chen and Dahlman 2004). The diffusion of IT and IT communication infrastructure were shown to have insignificant effects on national competitiveness, both of which are inconsistent with previous research in the area. The second critical contribution of this thesis suggests that for a typical country to utilise IT to improve its competitiveness, policymakers should focus principally on IT educational policies over and above efforts that target IT communication infrastructure and the diffusion of IT throughout its economy. In consistency with the measure of the IT education variable, educational policies targeting IT should focus on a skills and problem solving based approach, over syllabus orientated reforms. Taken together, findings from the educational reform literature, and the sizeable estimated lagged effect of national competitiveness in the model suggests that IT orientated reforms in the education systems are likely to be sustainable as well as effective. 6.2 Limitations & Directions for Further Research Whilst the simplicity of the measure of national competitiveness employed in the thesis in one light is refreshing, in another it may be viewed as overly simplistic. One may ask if it is it reasonable that the absolute value of GDP alone is sufficient to capture the intra-national and inter-national competitiveness of a nation. The analysis argues that this is sufficient, however does not objectively address this question. This is an important consideration, which is difficult to test as there is no absolute metric for national competitiveness. Whilst one approach is to take each measure on its own merits, a more rigorous analysis of this assumption would be favourable. Thus one direction of further research would be the further investigation of specific functional forms derived from the theoretical foundations which this thesis offers.

- 15. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 15 A second limitation concerns the sample used. In its current form, the model applies to the ‘typical’ nation, but says nothing about how the policies could change depending on factors such as the stage of development of a nation, or the strength of its national competitiveness. It is likely that policy recommendations may differ between the least and the most competitive nations. Instead the conclusions apply more directly to those around the average, and furthermore this range itself is not objectively considered. Kharlamova and Vertelieva (2013), for example, makes some advances identifying 5 country groups from 36 countries, and it would be interesting to extend his analysis, to a larger sample and then apply those groups to this DPD model. A final limitation to highlight concerns the data, as a multicollinearity issue prevents the estimation of the lagged effects of the IT variables of interest. This again departs from the consensus in the literature in that, as with national competitiveness itself, the IT related measures should be measured dynamically throughout an economy. An analysis of these dynamic effects would be a final worthwhile direction in which to take the analysis, potentially in a time series model to compute the long-run effects.

- 16. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 16 Appendices The Appendices are organised as follows. Appendix A 16 A.1 List of Abbreviations A.2 List of Countries and Regions A.3 Data Sources A.4 Cases of Missing Data Appendix B 19 B.1 Notes on Section 3.2 B.2 Selected results of the NC computations Appendix C 21 C.1 Control variables C.2 Full Empirical Estimations C.3 Test for Autocorrelaction Appendix A A.1 List of Abbreviations Abbreviation In Full DPD Dynamic Panel Data GCI Global Competitiveness Indicator GCR(s) Global Competitiveness Report(s) IMD Institute for Management Development IT Information and Technology WEF World Economic Forum

- 17. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 17 A.2 List of Countries and Regions Albania Algeria Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belgium Benin Bolivia Bosnia & Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Chad Chile China Colombia Costa Rica Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Estonia Ethiopia Finland France Gambia, The Georgia Germany Greece Guatemala Guyana Honduras Hong Kong SAR Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Korea, Rep. Kuwait Kyrgyz Republic Latvia Lesotho Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia, FYR Madagascar Malaysia Mali Malta Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Mongolia Morocco Mozambique Namibia Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Nigeria Norway Pakistan Panama Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Qatar Romania Russian Federation Singapore Slovak Republic Slovenia South Africa Spain Sri Lanka Sweden Switzerland Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Venezuela Vietnam Zambia

- 18. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 18 A.3 Data Sources Data Source Global Competitiveness Index World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Reports The 12 Pillars of Competitiveness Mobile Phone Subscriptions Fixed Broadband Subscriptions Individuals using the Internet Availability of Latest Technology Firm Level Technology Absorption FDI & Technology Transfer Quality of Maths & Science Education Internet Access in Schools GDP in 2005 US Dollars World Bank Databank GDP in Annual Percentage change Exports Volumes (indexed to 100 in the year 2000) Export Volume Annual Percentage change IMF Databank A.4 Missing Data Data is fully collected for all countries listed above, over the period 2006-2013 inclusive, with two exceptions: GCR data for Tunisia in the year 2012 GCR data for Tajikistan in the year 2013 The selection of countries for use in the analysis is based on the criteria that there is data in the vast majority of waves. Data is recorded as 0 for all missing values. Given the size of the dataset used, this is unlikely to significantly affect the results of the model, and the conclusions drawn.

- 19. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 19 Appendix B B.1 Notes on Section 3.2 The optimization problem of Equation (3) may be equivalently expressed as: , , , 2 [0,1] 1 1 (1 )argmin in sample i t i t i t T N t i Rank GCI Rank Y X (8) Where ,i tY represents the GDP of country i in year t, normalized to [0,1] ,i tX represents the exports of country i in year t, normalized to [0,1] ,i tGCI is the (absolute) score on the Global Competitiveness Index of country i in year t. 0,1 is the weight of GDP It should be noted that the in-sample rank of the GCI is computed. Put differently, countries are ranked only against the other countries which are considered in this thesis. Therefore this ranking will differ slightly from the rankings produced by the Global Competitiveness Reports. The difference is likely to be greater towards the lower end of the rankings. As the GCR is published for overlapping years, the start year is taken as the base. Therefore the data from the 2010-2011 is taken as the year 2010 for use in the analysis. Furthermore, note that the variables ,i tY and ,i tX are taken as exogenous for each of the four cases combination of unit measures in Table 1. This allows the problem to be solved systematically. Combining the notion in Equations (3) and (8) asserts that (i) , , in sample i t i tGCI Rank GCI , and (ii) ,i tNC , ,(1 )i t i tRank Y X B.2 Selected Results of the NC optimization computation The table below reports a selection of the results for the National Competitiveness measures derived above. Combinations using the continuous variable were computed in increments of 0.01 from 0 to 1 (inclusive). Therefore 101 measures for each of the four cases are computed however four corner computations are repeated. Thus, the total number of combinations considered is equal to (4 101) 4 400x .

- 20. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 20 Combination Sum of Square difference in ranking, over all nations and waves GDP Units Export Units 0 -- Absolute Levels 2, 480, 620 0 -- % Change 2, 181, 965 0.2 Absolute Levels % Change 2, 256, 292 0.4 Absolute Levels % Change 2, 039, 576 0.6 Absolute Levels % Change 1, 785, 282 0.8 Absolute Levels % Change 1, 428, 954 0.9 Absolute Levels % Change 1, 129, 588 1* Absolute Levels* --* 620, 002* 1 % Change -- 2, 755, 961 * Denotes the optimal combination.

- 21. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 21 Appendix C C.1 Control Variables Eleven of the twelve Pillars of Competitiveness are employed as controlling variables. A full description can be found in the WEF Global Competitiveness Report. Control Variable Associated Pillar in the GCR Institutions 1 Infrastructure 2 Macroeconomic Environment 3 Health & Primary Education 4 Higher Education & Training 5 Goods Market Efficiency 6 Labour Market Efficiency 7 Financial Market Development 8 Market Size 10 Business Sophistication 11 Innovation 12 The 9th Pillar in the GCR, Technological Readiness, is not included in the model employed in this thesis as it is strongly influenced by the combination of: (i) the availability of the latest technology; (ii) the firm level of technology absorption; (iii) the FDI and technology transfer variables; and (iv) The number of fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 citizens Other factors also play a role, but the pillar is too similar to two of the constructed variables of interest in this thesis, namely the IT communication infrastructure and the diffusion of IT variables when contrasted with Table 2 in Section 3.3.

- 22. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 22 C.2 Full Empirical Estimation This subsection reports the full estimations of the two-step Arellano-Bond DPD Model specified in Equation (4). All variables are in first differences. Variable Coefficient Estimate (Robust Standard Errors*) P value Lag of National Competitiveness 0.4228 (0.1330) 0.001 IT Communication Infrastructure -0.0005 (0.0032) 0.871 Diffusion of IT 0.0038 (0.0078) 0.627 IT Education 0.0299 (0.0122) 0.014 Institutions -0.0042 (0.0091) 0.644 Infrastructure 0.0168 (0.0087) 0.052 Macroeconomic Environment 0.0124 (0.0051) 0.015 Health & Primary Education 0.0297 (0.0085) 0.000 Higher Education & Training -0.0042 (0.0139) 0.763 Goods Market Efficiency 0.0053 (0.0069) 0.441 Labour Market Efficiency -0.0176 (0.0072) 0.014 Financial Market Development 0.0125 (0.0073) 0.086 Market Size 0.0975 (0.0373) 0.009 Business Sophistication 0.0208 (0.0090) 0.020 Innovation -0.0194 (0.0089) 0.031 Number of Instruments: 35 Number of Observations: 696 Number of Groups: 116 Wald 2 15 statistic: 249.44 * Robust Standard Errors are adjusted for clustering by country. Dependent Variable: National Competitiveness.

- 23. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 23 C.3 Test for Autocorrelation Arellano-Bond test for zero autocorrelation in first differenced errors. Null Hypothesis: No Autocorrelation. Order z P value 1 -1.2654 0.2057 2 -1.1512 0.2497 The Null hypothesis of No Autocorrelation is not rejected.

- 24. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 24 Bibliography Arellano, M., and Bond, S. (1991), ‘Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations’, The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 277-297. Chen, D. H. C., and Dahlman, C. J. (2004), ‘Knowledge and Development: A Cross-Section Approach’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 3366, Washington DC. Cohen, W. M., and Levinthal, D. A. (1989), ‘Innovation and learning: the two faces of R&D’, Economic Journal, vol. 99, pp. 569-596. Cohen, W. M., and Levinthal, D. A. (1990), ‘Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation’, Administrative Sciences Quarterly, vol. 35, pp. 569-596. Dahlman, C. J., and Brimble, P. (1990), ‘Technology Strategy and Policy for Industrial Competitiveness: A Case Study in Thailand’, World Bank Industry and Energy Department Industry Series Working Paper, no. 24, Washington, DC. Delgado, M., Ketels, C., Porter, M. E., and Stern, S. (2012), ‘The Determinants of National Competitiveness’, NBER Working Paper no. 18249, Cambridge Massachusetts. European Commission (2004), ‘Strengthening Competitiveness through Cooperation’, European Research in Information and Communication Technologies, Brussels. Hargreaves, A., and Goodson, I. (2006), ‘Educational Change Over Time? The Sustainability and Nonsustainability of Three Decades of Secondary School Change and Continuity’, Educational Administration Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 3-41. IMD World Competitiveness Centre: Methodology [online], Available at http://www.imd.org/wcc/research-methodology/ Last Accessed 18th April 2015. Johnston, L., and Chinn, M. D. (1996), ‘How well is the United States competing? A comment on Papadakis’, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, vol. 15, pp 68-81. Kharlamova, G., and Vertelieva, O. (2013), ‘The International Competitiveness of Countries: Economic-Mathematical Approach’, Economics & Sociology, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 39-52. Kubielas, S., and Olender-Skorek, M. (2014), ‘ICT modernization in Central and Eastern Europe: A Schumpeterian catching up perspective’, International Economics and Economic Policy, vol. 11, no. 1-2, pp. 115-136. Kumar, M., and Charles, V. (2009), ‘Productivity growth as the predictor of shareholders’ wealth maximization: An empirical investigation’, Journal of CENTRUM Cathedra, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 72-83. Löfgren, A. (2008), ‘ICT Investment Evaluation and Mobile Computing Business Support for Construction Site Operations’, Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems, vol. 6, no. 29, [online], Available at

- 25. EC331 Research in Applied Economics 1203596 25 http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1146&context=sprouts_all Last accessed 18th April 2015. Mittal, S. K., Momaya, K. S., and Sushil, S. (2013), ‘Longitudinal and Comparative Perspectives on the Competitiveness of Countries: Learning from the Technology and the Telecom Sector’, Journal of CENTRUM Cathedra, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 235-256. Momaya, K. (2008), ‘Evaluating country competitiveness in emerging industries: learning for a case of nanotechnology’, Journal of International Business & Economy, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 37-58. Mowery, D. C., and Oxley, J. E. (1995), ‘Inward technology transfer and competitiveness: the role of national innovation systems’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 19, pp. 67-93. Nelson, R. R. (1990), ‘US technological leadership: where did it come from, and where did it go?’, Research Policy, vol. 19, pp. 117-132. Nelson, R. R. (1992), ‘National innovation systems: a retrospective on a study’, Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 1, pp. 347-374. Porter, M. E. (1990), ‘What is National Competitiveness?’, Harvard Business Review, March issue [online], Available at https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations/ar/1 Last accessed 18th April 2015. Riley, K. A. (2004), ‘Schooling the citizens of tomorrow: the challenges for teaching and learning across the global north/south divide’, Journal of Educational Change, vol. 5, pp. 389-415. Sahlberg, P. (2006), ‘Education reform for raising economic competitiveness’, Journal of Educational Change, vol. 7, pp. 259-287. The Global Competitiveness Report 2014-2015, World Economic Forum [online], Available at http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GlobalCompetitivenessReport_2014-15.pdf Last accessed 18th April 2015. Yapp, C. (2001), ‘What does Katie Stowe Need to Know?’, Presentation to the Planning for Teaching and Learning in the 21st Century Conference, Newcastle, UK; reported in Riley, K. A. (2004), ‘Schooling the citizens of tomorrow: the challenges for teaching and learning across the global north/south divide’, Journal of Educational Change, vol. 5, pp. 389-415. Zamora-Torres, A. I. (2014), ‘Countries’ Competitiveness on Innovation and Technology’, Global Journal of Business Research, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 73-83.