6.supply chain 2

- 1. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1463-5771.htm BIJ 18,6 Supply chain collaboration performance metrics: a conceptual framework 856 Usha Ramanathan Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Angappa Gunasekaran Department of Decision and Information Sciences, Charlton College of Business, University of Massachusetts, North Dartmouth, Massachusetts, USA, and Nachiappan Subramanian Department of Mechanical Engineering, Thiagarajar College of Engineering, Madurai, India Abstract Purpose – Successful implementation of supply chain collaboration (SCC) by Wal-Mart has encouraged many manufacturing companies, such as Procter & Gamble, Hewlett-Packard Co, and West Marine Products Inc., to initiate collaboration. Subsequently, collaboration between suppliers and retailers has become a common practice in many recent supply chains. However, measuring the benefits of collaboration is still a big challenge. Based on supply chain literature and practice, this paper aims to propose a conceptual framework and a standard set of metrics to evaluate the performance of SCC. Design/methodology/approach – The authors discuss two case studies to validate the proposed model. The case study discussions are appropriate to understand the usage of different performance metrics in initial and advanced stages of collaboration. Findings – From the case study it is recognized that the collaborating members in the supply chain are not able to visualise all possible benefits of collaboration. To surmount this issue, the paper proposes a framework to study the performance of companies involved in initial and advanced stages of collaboration. Originality/value – The classification suggested in this paper on different stages of collaboration and related metrics can guide researchers and practitioners in manufacturing companies to evaluate the performance of SCC. Keywords Collaboration, Performance metrics, Supply chain, Supply chain management, Manufacturing industries Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction Supply chain involves raw material and component suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers until the finished products reach end customers. It has been generally agreed that the performance of the entire supply chain could be improved through collaboration (Barratt and Oliveira, 2001; Seifert, 2003). The literature reveals that businesses have been Benchmarking: An International collaborating in general for several decades in many different forms for varied purposes. Journal Some of the purposes of collaboration are to improve overall business performance, Vol. 18 No. 6, 2011 pp. 856-872 reduce cost, increase profit, and improve forecast accuracy (McIvor et al., 2003; McCarthy q Emerald Group Publishing Limited and Golicic, 2002; Matchette and Seikel, 2004). Lucrative benefits of collaboration can 1463-5771 DOI 10.1108/14635771111180734 encourage many supply chain members to initiate the process of collaboration.

- 2. In general, businesses with similar objectives work closer to achieve excellence in common Supply chain supply chain processes such as planning, forecasting, and replenishment. The extent and performance intensity of collaboration may vary greatly based on business objectives, which in turn decide the success of supply chain collaboration (SCC) (Larsen et al., 2003, ECR Europe, metrics 2002). Owing to cost involved in initiating collaboration, sometimes SCC will be more viable to suppliers than buyers (Chen et al., 2007) or more viable to buyers than suppliers (Dong and Xu, 2002). Hence, in the process of SCC, each business needs to weigh their 857 current scenario with past and future. This may include periodic review of performance of collaboration using a standard set of metrics. Periodic reviews can help improve collaboration agreement with other supply chain members regularly. In the literature of SCC, many performance measures have been suggested including cost, benefits such as profit, lead time, customer satisfaction, inventory, forecast accuracy, etc. (Chang et al., 2007; Kim and Oh, 2005; Angerhofer and Angelides, 2006; Simatupang and Sridharan, 2005). Majority of supply chain metrics in the literature are measures of internal performance of a firm (Lambert and Pohlen, 2001; Barratt, 2004). If information on performance of supply chain is shared with other partners, then it could possibly improve the overall efficiency of the supply chain. Simatupang and Sridharan (2004a, b) have proposed a collaborative performance system consisting of three cycles with respect to collaborative enablers to improve operational performances. On reviewing the literature of SCC, we have identified that the performance metrics for SCC were not given adequate importance as compared to general supply chain performance. We have also found that there is no specific set of metrics readily available to supply chain members to measure their performance in SCC at pilot and advanced stages of collaboration. Hence, we believe that identifying the key metrics to measure the performance of SCC from suppliers’ or buyers’ viewpoint is indispensable. Therefore, in this paper, we propose a conceptual framework to measure performance of SCC at initial and advanced stages of partnership. In line with supply chain literature of collaboration and performance measurement we have developed a conceptual model for performance metrics. The major objective of this paper is to suggest a specific set of metrics at early and advanced stages of collaboration. To facilitate this study, we have attempted to understand the current status of collaboration in SC through literature review. Then we have conducted two case studies as this approach will be appropriate to have an in-depth knowledge on the selected cases in achieving our research objective (Yin, 1994). For case study, we have considered two manufacturing companies at two different stages of collaboration. One of the case study companies is practicing “collaborative planning forecasting and replenishment (CPFR)” for the past four years, whereas the other company is recently involved in CPFR. Choice of these two cases has been instrumental in relating our literature findings to match with initial and advanced stages of collaboration. Further in this article SCC with respect to literature review refers to a combination of different supply chain practices, whereas in the context of case study, SCC is specific to CPFR practice. This paper starts with an introduction to role of collaboration in supply chain and a review of literature related to performance metrics of SCC. Section 3 proposes various functional drivers and enhancers for constructing SCC. This section also describes a conceptual framework on performance metrics of SCC. Section 4 describes and analyses the SCC at two case companies that practice collaboration at two different stages. The paper concludes with some scope for future research.

- 3. BIJ 2. SCC and performance 18,6 2.1 Role of collaboration in supply chain In order to improve supply chain processes and to gain support from other supply chain partners, several supply chain management practices such as vendor managed inventory (VMI), efficient consumer response (ECR), continuous replenishment (CR), and electronic data interchange have been suggested in the literature. In VMI (developed in 858 the mid-1980s) the customer’s inventory policy and replenishment process are managed by vendor or supplier. However, VMI’s supply chain visibility has not been found powerful enough to avoid the bullwhip effect completely (Barratt and Oliveira, 2001). Here, bullwhip effect refers to amplification of demand fluctuations from downstream to upstream in supply chain. This drawback of VMI has been successfully modified in the later versions in different sectors and the derived versions are termed as ECR, CR, etc. Ever increasing supply chain demands have led to the invention of CPFR (introduced in late 1990s), another supply chain management practice, which incorporates planning, forecasting, and replenishment under a single framework (Fliedner, 2003). CPFR has been introduced as a pilot project between Wal-Mart and Warner-Lambert in the mid-1990s aiming to develop a supply chain responsive to customer demand. CPFR is a new collaborative business perspective that combines the intelligence of multiple trading partners in the planning and fulfilment of customer demand by linking sales and marketing information (VICS, 2002). The CPFR framework encourages all partners to share sales, inventory, forecast, and all related information to improve forecast accuracy (VICS, 2002). Such information sharing believes to avoid bullwhip effect (Lee et al., 2000; Cachon and Fisher, 2000). This information exchange is made possible through advanced technology in many retail sectors (for example, Wal-Mart’s electronic point of sale data is made available to all its collaborating partners). Quality of information being exchanged among SC partners’ influences the supply chain processes and forecast accuracy (Forslund and Jonsson, 2007). Some of the benefits of SCC such as cost reduction, inventory reduction and forecast accuracy are revealed through many case studies (Smaros, 2007; Danese, 2007) and some mathematical models (Lee et al., 2000; Aviv, 2007); but the indicators for measuring the benefits of collaborations are not clear and precise. We have endeavoured to group the performance metrics of SCC, identified from the literature, in the next section. 2.2 Performance metrics for SCC The primary objective of initiating collaboration in any supply chain is to enhance the overall performance of supply chain and this can be achieved through the collective effort of all supply chain members (Angerhofer and Angelides, 2006). Barratt (2004) identified managing change, cross-functional activities, process alignment, joint decision making, and supply chain metrics as essential elements for successful SCC. In these five elements, the first two are related to initial front-end agreement among SC members and their involvement in SCC. Power sharing and leadership issues are also included in the front-end agreements. Whilst, supply chain processes and joint decision making are commonly used in all type of SCC, the supply chain metrics are different for inter- and intra-– organizational collaborations. Internal and logistics performance measures are also discussed in recent literatures of SCC. In this paper, we have tried to identify all possible performance metrics from the literature of SCC with respect

- 4. to different stages of collaboration. In this attempt, first we have checked the motive of Supply chain SCC as this will indirectly indicate SC processes to be evaluated. performance Like-minded people or businesses with similar objectives come closer to form a group. One or more of them take a leading role in initiating formal collaboration. Then, metrics interested supply chain members make front-end agreement (VICS, 2002). Top management decides cross-functional activities and involvement of various departments in collaboration at functional/operational and strategic level (Ireland and 859 Crum, 2005). Performance at this stage of collaboration is measured through operational efficiency and risk/return ratio. Hence, business strategy is been considered as one of the metrics as it measures the functional capability of the SC member for varying market demand (Akkermans et al., 1999; SCOR model). Although CPFR suggests equal opportunities to the SC members in collaboration, this is not reflected in practice. Hence, the order of dominance and decision sharing create a win- win or win- or lose-lose situation in SCC (Kim and Oh, 2005). Partnership revival or inclusion is considered in case of unexpected loss/profit or reduction in profit. As various processes of supply chain (namely planning, forecasting, production, and replenishment) have impact on cost, profit, inventory levels, stock outs and resource measures, these measures have been deemed important by many academics and practitioners (Angerhofer and Angelides, 2006; Gunasekaran et al., 2001). Table I lists the measures of SC from the literature. Supply chain models developed after inception of CPFR incorporated some improvement to the original CPFR framework by measuring its performance Essential Role of SCC elements for SCC Performance metrics Authors Collaborative Cross-functional Business strategies (functional Akkermans et al. (1999) and planning and activities capabilities), processes SCC (2001) – SCOR model production, (operational efficiencies), stake decision making holders view (risk/return ratio) SCC leadership Order of dominance and decision Kim and Oh (2005), and power sharing Simatupang and Sridharan sharing (2004a,b), and Aviv (2007) Process Cost, profit, excess inventory, Beamon (1999), Lambert alignment stock-out, resource measure and Pohlen (2001), Dong and Chen (2005), and Emmet and Crocker (2006) Information Joint decision Impact of information quality on McCarthy and Golicic sharing, making forecasting (2002), Forslund and forecasting Information Jonsson (2007), decision making sharing and Raghunathan (2001), and forecasting Chang et al. (2007) Managing Reliability, reactivity/flexibility Forme et al. (2007), changes Angerhofer and Angelides (external and (2006), and Barratt and internal) Oliveira (2001) Replenishment, Internal and Inventory and stock position, Cachon (2001); Ettl et al. Table I. decision making logistics stock out, lead time, internal (2000), Aviv (2007), Simchi- Supply chain performance service rate, cross-functional Levi and Zhao (2005), and performance metric and capability, logistics efficiency Chen and Paulraj (2004) its correlation with SCC

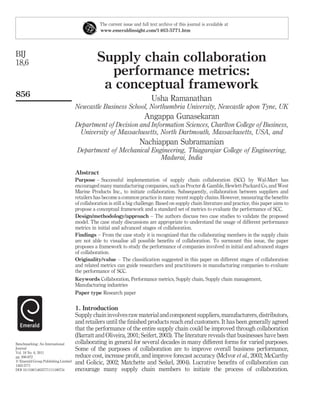

- 5. BIJ and identifying areas of improvement. Stank et al. (2001) and Rowat (2006) attempted to 18,6 relate internal and external collaboration with logistical service performance. McCarthy and Golicic (2002) used responsiveness along with other basic measures – cost and revenue. Chang et al. (2007) claimed that “Augmented CPFR” (an improved model with third party information) is a better model with improved forecast accuracy and inventory. In a recent literature on SCC, capacity utilization and supply chain flexibility 860 have also been considered as measures of performance (Angerhofer and Angelides, 2006 and Aviv, 2007). In the literature, flexibility, and reactivity are used as synonyms to represent ability of the supply chain in adapting to the changes (Forme et al., 2007; Angerhofer and Angelides, 2006; Barratt and Oliveira, 2001). Normally, only the changes internal to an organization have been considered for this purpose. Responsiveness of the SCC is another metric that has not been discussed adequately in the literature. In recent years, information exchange has become integral part of SCC processes and hence it also needs to be measured periodically. Though quality of information is important (Forslund and Jonsson, 2007; Forme et al., 2007), use of technology for improving quality of information has not been adequately stressed in the literature. If one could measure the responsiveness of SC on timely information (timely information to act upon), this will measure the importance of information exchange in SCC to a larger extent. Measures of responsiveness and flexibility can reflect a wider perspective of supply chain performance incorporating suppliers and buyers. Hence, comprehensive view of performance metrics of SCC need to involve all the metrics mentioned in Table I along with a few elemental measures such as managing change (use of technology), sharing performance metrics with customer (responsiveness), and sharing performance metrics with suppliers (flexibility). While, flexibility measures the ability of adapting to the changes effectively with available resources, responsiveness can measure the response of the supply chain for any unexpected changes in demand. Responsiveness is usually related with innovative products or products with short lead time which decides the level of collaboration needed (Lee, 2002). Recently, many companies have started giving more emphasis on the use of information technology and hence IT has become an integral part of SCC (VICS, 2002). For example, use of barcode and radio frequency identification technology in the retail sector helps to track point of sale, which in turn makes supply chain more responsive (Ireland and Crum, 2005). Such technological advancement makes communication between retailer and manufacturer easier. Hence, in this paper we have included the use of technology as one of the performance metrics of SCC. We augment the metrics suggested in the literature with three other important measures namely flexibility responsiveness and technology in our comprehensive view of performance metrics of SCC (Figure 1). Applying all the above measures identified from the literature into a single model to evaluate a SCC will be a complicate task. However, the objective of SCC and front-end agreements between SC partners can help to decide on which measures need to be used. To our knowledge, none of the models listed in Table I has discussed performance metrics at different stages of SCC. Hence, in this paper, we have attempted to align all the identified performance measures at two different stages of SCC. In this line, we have developed a conceptual framework on performance measurement of SCC.

- 6. Technology Supply chain performance metrics Supplier Manufacturer Retailer Flexible Responsive 861 Cost, profit, stock-out, and resource measure , Business strategies (functional capabilities), processes (operational efficiencies), stake holders view (risk/ return ratio), Impact of information quality on Figure 1. forecasting, Order of dominance and decision sharing, Inventory & stock position, stock out, lead time, internal service rate or cross functional capability, logistics efficiency, Reliability, reactivity Comprehensive view of performance metrics Metrics from the literature of SCC 3. Conceptual framework for SCC and related metrics SCC transforms the partnership from narrower perspective of intra-organizational level to wider perspective of inter-organizational level (Barratt, 2004). This also incorporates all or many personnel in strategic- tactical- and operational level. Long-term business plan is generally decided at strategic level, short-term planning and forecasting is made at tactical level and day-to-day operations are planned and executed in operational level. Performance measurement will be complete only if it is conducted at all these three levels (Gunasekaran et al., 2001, 2004). Generally, all the companies practicing SCC initially test their performance under collaboration in a pilot stage. Successful pilot stage may facilitate in further collaboration (Cassivi, 2006). This is evident from several cases such as Wal-Mart and Procter and Gamble, and also through our case study analysis of two manufacturing firms, discussed in the next section. The companies need to have different set of performance metrics specific to their stage of collaboration. At the same time, the stage of collaboration is decided by various elements. The elements which form the basis for initiation of collaboration are common business objectives and supply chain processes and can be termed as functional drivers. Other elements such as degree of involvement (joint decision making), use of technology (managing change) and incentive sharing, which enhance or support the collaboration can be classified as enhancers. We feel that SCC has two distinct stages – pilot stage when the initial attempts are made to test SCC, and advanced stage when all the partners are convinced of SCC and are fully committed. Accordingly, the metrics to measure performance of SCC should be different for pilot and advanced stages. Measuring functional drivers can give comprehensive idea on performance of SCC at pilot stage. If the company had other business goals of achieving responsive supply chain for changing demands, it might have enhancers in collaboration and related metrics. Measuring functional drivers and enhancers collectively will represent the performance of SCC in its advanced stage. The essential elements of SCC suggested by Barratt (2004) serve as a backbone for proposing this conceptual framework and related metrics. 3.1 Metrics to measure “functional drivers” As mentioned earlier, functional drivers of SCC include business objectives and SC processes. Business objectives, such as financial and operational, are main factors to SCC. Supply chain members who intend to establish their business are keen in identifying partners with similar objectives to have long-term collaboration.

- 7. BIJ As the first step for collaboration, the companies form a front-end agreement; this needs 18,6 to be reviewed periodically for any changes and can be measured through cost-benefit analysis. Supply chain processes in CPFR framework are divided into four main stages namely planning, forecasting, production, and replenishment (VICS, 2002). But in the recent years, handling product returns has also become one of the foremost reasons for SCC 862 (Lambert and Cooper, 2000). Hence, we have included “return” as one more stage in the supply chain processes. These supply chain processes can be measured through different possible measures suitable to the adopting company. Some of the suggested metrics in the literature are capacity utilization, adherence to plan, inventory, stock-outs, and feedback on returns (Aviv, 2007; Cachon and Fisher, 2000). The feedback from retailers will be one of the effective measures, as it provides opportunity for manufacturer to improve the product quality or avoid future error or improve sales based upon feedbacks of returned items. The flexibility, which measures the efficiency of SCC with upstream members (suppliers), can be measured through timely delivery of raw material, availability of material at the time of production on urgent orders, and service rate. 3.2 Metrics to measure “enhancers” It is generally agreed that collaboration among supply chain members is built encompassing their business objectives. When the top management support more collaboration the company will establish collaboration with more partners and may invest more on SCC. Hence, degree of involvement is the first enhancer of SCC. Degree to which supply chain partners involve in collaboration is captured through investment on collaboration and sharing decision making. A great deal of business is based on the information sharing and proper use of data. Accelerated information sharing among all supply chain will increase the reliability of the order generation (VICS, 2002). Improved forecast accuracy is another motivating factor of SCC. Achieving forecasting accuracy is mainly through information sharing among members of SCC. Quality of information adds more value to the process of forecasting and hence it needs to be measured periodically. Improved forecasting accuracy will be an indicator of effective information exchange. If technology is used for exchanging information, its efficiency can be measured through accessibility of information by supply chain members. Based on this, any business can make decisions on investment on technology. Incentive sharing is another important enhancer of SCC, which attracts more members in collaboration and hence incentive sharing agreement needs periodic revision. Regular contacts among members of SCC and feedback on performance of supply chain will help to revive incentive sharing agreement. Responsiveness, which measures the efficiency of SCC with changing demand in downstream (retailers), could be measured through product availability. 3.3 Conceptual framework for the whole SCC Every company taking part in SCC needs to decide on the performance metrics on functional drivers and/or enhancers to track its success. The conceptual model developed based on the above discussions is shown in Figure 2. The desired metrics essential for measuring SCC is listed out in Figure 2 under categories functional

- 8. Supply chain Functional Drivers performance Processes Plan, Forecast, Produce, Business objectives Metrics to measure the performance of SCC metrics Financial & Operational Replenish and Return Measuring Functional drivers - Front end agreements (mutual agreements) - Business strategy (Profit and loss) Initiate Collaboration (Initial stage) - Processes (production, forecast accuracy, replenishment and handling of returned products) 863 - Capacity utilization (production efficiency) - Adherence to plan (plan vs. actual) - Availability of material (resource planning efficiency) Manufacturer - Inventory (Stock outs /Excess) (Evaluator) - Service rate (Product lead time measure) Strategic - Feedback Supplier Retailer Measuring Enhancers Tactical - Decision making sharing (involvement of partners, Operational involvement in information exchange and forecasting) - Investment on communication technologies (support and financial measure) - Use of technology (communication, information exchange & forecasting) Support Collaboration (advanced stage) - Information sharing &communication (Frequency and access) Degree of Information sharing, forecasting - Information quality (accuracy) Incentive - Forecasting involvement and technology - Product availability - Feedback Enhancers Overall effectiveness of SCC Responsiveness + Flexibility + Technical excellence Figure 2. Proposed metrics for SCC framework drivers and enhancers. In addition, measures on responsiveness, flexibility and technical excellence can help the company to assess the overall effectiveness of SCC. Based on this assessment, further changes to the collaboration can be incorporated if needed. 4. SCC in practice – case study observations Collaboration and its suitability with the retail sector have been rigorously examined by numerous researchers (Smaros, 2007; Holweg et al., 2005; Rowat, 2006). In the recent literature, design for SCC is suggested by Simatupang and Sridharan (2008). But, research on performance metrics suitable to manufacturing companies is still in its infancy. This paper studies the performance metrics used in a packaging firm at their initial (pilot) stages of collaboration. Case of textile company has been used to analyze the use of metrics in advanced stage of collaboration. The choice of a case is important as it explores the research question (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994) namely the metrics to measure performance of SCC. In this research, case studies aim to understand SCC and performance metrics used at various stages of collaboration. Case 1 is a packaging firm has been involved in SCC with their downstream members for the past 18 months to control inventory and to avoid obsolescence. Case 2 is a textile company initiated collaboration before four years and has well established SCC with their buyers mainly for promotional sales and forecasting. Although, both these companies are in SCC, the level of collaboration is different and hence their practice on performance measurement is also different.

- 9. BIJ We have conducted case studies in two stages. The first stage has been intended to 18,6 study existing SCC and assess its reliability. The second stage of case study is mainly for the purpose of understanding the metrics used in SCC. Interviews and frequent visits are the methods adapted to perform the above case studies. Interviews have been conducted with dependable officers responsible for collaborative relationship among partners, information exchange, forecasting, and operations. A few interviews have 864 also been conducted with decision makers. The first author has visited the company several times in the span of two years in order to observe the changes in current collaborative arrangement in comparison with the sales and order data. Initially, Nvivo tool has been used to analyse the interview transcripts. Brief description of the case companies will help readers to understand the SCC in practice. 4.1 Description of case 1 Company background. The packaging company (Case 1) considered for this case was established in 1966. In its early years, Case 1 produced waterproof packaging materials and gradually expanded its production base to produce flexible intermediate bulk containers (FIBC). In the local market, Case 1 is the first manufacturer introducing FIBC and has nearly 50 percent market share. After 1996, the company has started to export its products to many international companies in petrochemical industry, mineral industry, dyes industry, and selected products in pharmaceutical industry. Case 1 has maintained quality and durability of the packaging material by treating it with ultra violet (UV) radiation. The company’s global operation requires them to have partnership with their supply chain partners to survive in the competitive international business. Supply chain at Case 1 before collaboration. Raw material suppliers to packaging industry are available in plenty and hence competition to become a partner in supply chain is very fierce. Though many raw material suppliers are available, the company prefers to have collaboration with a few local markets. In this case, supplier-manufacturer collaboration is simple and straight forward. As the company has been maintaining a good relationship with their clients, supply chain members exchanged information related to inventory and demand. The company builds their demand forecast based on those information from SC members and resulted in poor forecast accuracy. This has promoted the company to focus on information accuracy and related problems. Owing to lack of formal agreement among SC members, the information accuracy has always been uncertain. Without clear vision on incentive of SCC, no supply chain member has been committed for success of supply chain performance. As a consequence, forecasted demand from downstream member is 25-30 percent higher than the actual orders. The company essentially produces to order, though it also produces a limited amount to stock. About 50 percent of the basic common production process used to be completed based on initial forecast made through available information. As a result, the company has been facing a problem of excess inventory of finished and unfinished products. Recently, Case 1 has realized the importance of collaborative agreement to improve the information quality and accuracy. New government environmental regulation has forced the company to make use of raw materials and UV treatment of bags. This has necessitated the company to upgrade their products or to sell their product quickly before implementation of new sales regulation. Ultimately the company has incurred a loss at the end of 2006.

- 10. As-is scenario. In the beginning of the year 2007, the top management of the Supply chain company engaged in formal supply collaboration to revive its performance. The performance company has adopted vertical collaboration with suppliers and customers as part of their external collaboration and also has maintained internal collaboration among metrics various departments. The company has adopted a transparent profit sharing policy for SCC and also assured timely delivery for their clients. These two features of SCC have helped them to get committed involvement of other members. Decision on profit 865 sharing has been bound to the duration of collaboration and proportion of share in SC activities. Front-end agreement among SC partners has clearly mentioned the role of each member in SCC. The company has incorporated 40 percent of their clients in collaboration in its pilot stage of SCC. Partners with similar business objectives and with further interest in future collaboration have worked together. At the same time, the company has not invested much on information technology in its pilot stage of SCC. Most of Case 1’s communication with their customers has been carried out through iMail Server (iMail is one of the advanced recent communication technology that works well even in the presence of other servers such as e-mail server, SMTP, POP3, and IMAP). The company has used information from other partners to make their demand forecast. This has been fundamental in minimizing forecast errors. Periodically, the company has measured performance of collaboration through simple measures such as cost, profit, timely delivery of goods to customers, inventory level, and forecast accuracy. The above given information on various performance metrics of SCC in Case 1 and their purposes are further detailed in Table II. At the end of the next 12 months (end of 2007), the company has achieved 20 percent inventory reduction and 10 percent overall cost reduction. Improved forecast accuracy has helped the company on production plan and expansion. Case 1 has reduced their safety stock level to 10 percent of expected demand as against its earlier 30 percent. 4.2 Description of case 2 Company background. Case 2 is a leading textile manufacturing and exporting firm located in the main lands of Asia. Case 2 exports to various countries across the globe. Customized products are embroidered dress materials with exclusive design, and made-to-measure finished cushions, pillows, and curtains. Standard products are embroidered material with multiple repeated designs and curtain materials. The company generally follows make-to-order strategy for its exports and local business of customized products. A small part of the business (standard products to local markets) follows make-to-stock strategy with very limited stock that minimizes inventory and obsolescence cost. Like Case 1, Case 2 also has a strong uninterrupted supplier base for raw materials. In order to compete with ever growing challenges, the company has been involved in SCC with other downstream members. Supply chain at Case 2 at initial stage of collaboration. Like any other company, Case 2 has intended to improve inventory and reduce obsolescence and hence it has involved in SCC with their suppliers and buyers. Its collaboration with suppliers signifies a confirmation of availability of material/resources at the time of production. Initial collaboration with buyers has been very successful to the company in terms of profit. Case 2 measures their performance every month and analyzes the area of improvement. Accordingly, at the end of every year (for the first two years) the company revives their front-end agreement with customers. Except the measure of handling product returns,

- 11. BIJ Metrics in use 18,6 Purpose Desired metrics Case 1 Case 2 Initial stage Initiate and maintain collaboration Front-end agreements x x Business objective (financial) Business strategy (profit or cost) x x 866 Supply chain process and business Processes processes On time production – x Forecast accuracy x x Timely replenishment x x Handling product returns – – Production process Capacity utilization – x Planning execution Adherence to plan – x Supplier collaboration Availability of material on time – x Inventory control Inventory (stock outs/excess) x x Production/replenishment Service rate – x Improvement of SCC Feedback – x Advanced stage Investment decision in Technology Use of technology – Future involvement in Decision making sharing collaboration x Investment in the state-of-the-art Investment on technologies (IT and technologies communication) x Improve SC processes and Information sharing No collaboration collaboration x Improve forecast accuracy and SC Information quality (accuracy) processes – Table II. Improve forecast accuracy Forecasting x Purpose of desired Improve inventory position Product availability x metrics in SCC for case Improvement of SCC Feedback x companies Efficient use of SCC Managing change of whole SCC x all the other measures suggested in our conceptual framework have been measured by the company during their initial period of SCC. On success of initial SCC, the company intends – to involve in further collaboration with long-term agreements and to engage in advanced collaboration. As-is scenario of Case 2. In the advanced collaboration, the company involves all SCC members into information sharing and collaborative forecasting. Transparent and timely information has helped them to arrive at a single forecast figure which improved the forecast accuracy. As production and resource planning are directly linked to this single forecast figure, the company has reported improved product availability and adherence to production plan. Case 2’s investment on information technology and communication devises has helped them to secure exclusive network for receiving and sending information on sales, inventory and production processes. This has effected in considerable reduction of logistics difficulties during the time of replenishment. The company expects to be benefited more from SCC and related metrics. The measures of performance of SCC in Case 2 and their purposes are given in Table II.

- 12. 4.3 Possible scenario with advanced SCC and related metrics Supply chain Although Case 1 was successful in terms of controlling inventory and related cost, the performance top management was not sure on further benefits of CPFR as performance metrics were not clear to them. In its pilot stage of collaboration, Case 1 aimed to improve their metrics inventory to avoid loss. In this stage, the company must check their efficiency in SCC through the list of metrics given under “measures of functional drivers”. But Case 1 used only four performance metrics, namely forecast accuracy, inventory level, timely 867 replenishment, and cost, during their pilot stage of SCC. We have suggested our proposed conceptual framework of performance metrics to identify the performance of SCC. The first result after implementing the suggested framework for performance metrics, the company has reported that they could identify their strength and weakness in SCC under evaluation of each metrics. After calculation, Case 1 officials have confirmed that they are in a good position after SCC and hence intended to continue further collaboration with most of the existing partners. They have also considered revising front-end agreement with some of the SCC members. The company has also showed their interest in adopting our proposed metrics for SCC framework as their standard measure. When the company moves to the advanced stage of collaboration, they need to measure the effectiveness of enhancers. Collective consideration of functional drivers and enhancers will help the company to identify its areas of improvement. This exercise should be repeated periodically to review the front-end agreement on collaboration. The cost-benefit analysis of both the companies at the end of 2007 has encouraged them to invest more on SCC. Hence, in the next stage of collaboration, Case 1 has decided to invest more on technology to gain access to their clients’ data on real time basis. They have believed that this could improve quality and visibility of information. So the company has decided to have set of metrics as given in Table II to measure performance of SCC at its second stage. However, Case 2 had a well established basic collaboration and now they are in an advanced stage of collaboration. Substantial benefit of SCC has encouraged Case 2 to involve in further collaboration at its next stage. They have also shown interest in exploring the suggested performance metrics in the advanced stage of collaboration. The company has measured almost all the measures suggested in our framework. “Product returns” have not been included in the inventory and hence product has not been realigned. In the advanced stage “use of technology” and “quality of information” have not been measured. But later during our discussion, the company has understood the importance of these two measures in their decision making. The performance of overall SCC through responsiveness, flexibility and technical excellence for managing changes is another metric that has been viewed important by the case company to improve their SCC. Table II represents the list of measures currently being used by the companies for measuring their performance in SCC. This table also lists the desired set of metrics at pilot and advanced stages of collaboration. By comparing these two columns of desired metrics and metrics in use in the Table II, it is clear that the company (Case 2) that aims to have advance collaboration use more number of metrics than Case 1 that practices pilot stage of collaboration. However, before establishing further collaboration, Case 1 has been advised to measure all the desired metrics to evaluate their SCC performance. This approach can be used as basic guidelines by any firm that is interested in SCC

- 13. BIJ to measure its performance. Based on the level of collaboration, the top management can 18,6 choose the metrics to evaluate its benefits of SCC. 5. Conclusion and scope for future research In this paper, we have identified several performance metrics from the existing literature and through two case studies. We have proposed a set of metrics to measure SCC at its 868 initial (pilot stage) and advanced stages. We have suggested including flexibility, responsiveness and use of technology as important measures in comprehensive view of performance metrics of SCC. While, flexibility measures the ability of adapting to the changes effectively with available resources, responsiveness can measure the response of the supply chain for any unexpected changes in demand. Evaluating the collaboration at the time of initiation is suggested through measurement of functional drivers. Tracking the benefits of collaborative arrangement by measuring enhancers would be ideal for decision makers to revisit their agreement on SCC. While analysing the case of packaging firm, we have identified that the technology is not necessarily a key obstacle but effective communication is vital. Proper uses of technology, flexibility, and responsiveness have been considered as important criteria for successful SCC by the case companies. Measures of evaluating these three SCC criteria are termed as overall performance metrics in the conceptual framework. Another important observation from the case analysis is that ample availability of raw material supply or suppliers will engage manufacturers in simple collaboration with their suppliers mainly for on time material availability. Meanwhile they try to establish strong collaboration with their buyers in order to improve the product sale, inventory control, etc. Incentive alignment in collaboration will be beneficial to all partners involved. One of the observations about utility of production facilities reveals that the support from suppliers helps to provide raw material on time to make use of the production capacity to its maximum. Meanwhile, relationship with buyers does have an indirect impact on production capacity utilization and planning as job allocation is based on demand. Both the case companies did not have close relationship with its suppliers compared to buyers. Further research is indeed necessary to identify the impact of closer partnership with suppliers. Manufacturers with high degree of collaboration may or may not perform well. But consistent intervention and necessary changes as required by the system will aid to improve the performance. In case of no improvement in the performance, the collaboration can be withdrawn or revamped with new set up. This case study reveals that the manufacture-to-order type of business requires more support from their buyers than their suppliers to exchange information, to improve forecasting accuracy, to avoid inventory and also to achieve overall performance in the supply chain. The same kind of research can be extended to manufacture-to-stock business or assemble-to-order type of businesses. Detailed survey-based analysis is also essential to validate the above framework in future and to standardise for various sectors other than manufacturing. The case study did not consider number of suppliers as an important factor due to the availability of sufficient suppliers and their readiness to serve. The main reason for such attitude is products from packaging industry have got more life and have more opportunity to sell in the other market’s before their value got eroded. But collaborative relationship with suppliers will help to reduce excess raw material inventory. By the way of allotting incentive, manufacturer can involve supplier in SCC.

- 14. Incentive can be considered as the indirect motivating factor for involvement of supply Supply chain chain members in collaboration in order to get overall performance lift in the supply performance chain process. Further research in this line will help to identify some more metrics related to performance measurement of collaborative supply chain. metrics References 869 Akkermans, H., Bogerd, P. and Vos, B. (1999), “Virtuous and vicious cycles on the road towards international supply chain management”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 19 Nos 5/6, pp. 565-81. Angerhofer, B.J. and Angelides, M.C. (2006), “A model and a performance measurement system for collaborative supply chains”, Decision Support Systems, Vol. 42, pp. 283-301. Aviv, Y. (2007), “On the benefits of collaborative forecasting partnerships between retailers and manufacturers”, Management Science, Vol. 53 No. 5, pp. 777-94. Barratt, M. and Oliveira, A. (2001), “Exploring the experiences of collaborative planning initiatives”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 31 No. 4, pp. 266-89. Barratt, M. (2004), “Understanding the meaning of collaboration in the supply chain”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 30-41. Beamon, B.M. (1999), “Measuring supply chain performance”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 19 Nos 3/4, pp. 275-92. Cachon, G. (2001), “Exact evaluation of batch-ordering policies in two-echelon supply chains with periodic review”, Operations Research, Vol. 49 No. 1, pp. 79-98. Cachon, G.P. and Fisher, M. (2000), “Supply chain inventory management and the value of shared information”, Management Science, Vol. 46 No. 8, pp. 1032-48. Cassivi, L. (2006), “Collaboration planning in a supply chain”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 249-58. Chang, T., Fu, H., Lee, W., Lin, Y. and Hsueh, H. (2007), “A study of an augmented CPFR model for the 3C retail industry”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 12, pp. 200-9. Chen, I.J. and Paulraj, A. (2004), “Towards a theory of supply chain management: the constructs and measurements”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 22, pp. 119-50. Chen, M., Yang, T. and Li, H. (2007), “Evaluating the supply chain performance of IT-based inter-enterprise collaboration”, Information & Management, Vol. 44, pp. 524-34. Danese, P. (2007), “Designing CPFR collaborations: insights from seven case studies”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 181-204. Dong, M. and Chen, F.F. (2005), “Performance modeling and analysis of integrated logistic chains: an analytic framework”, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 162, pp. 83-98. Dong, Y. and Xu, K. (2002), “A supply chain model of vendor managed inventory”, Transporation Research Part E, Vol. 38, pp. 75-95. ECR Europe (2002), European CPFR Insights, ECR European facilitated by Accenture, Brussels. Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989), “Building theory from case study research”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 532-50. Emmet, S. and Crocker, B. (2006), The Relationship – Driven Supply Chain, Gower, Aldershot.

- 15. BIJ Ettl, M., Feigin, G.E., Lin, G.Y. and Yao, D.D. (2000), “A supply network model with base-stock control and service requirements”, Operations Research, Vol. 48 No. 2, pp. 216-32. 18,6 Fliedner, G. (2003), “CPFR: an emerging supply chain tool”, Industrial Management þ Data Systems, Vol. 103 Nos 1/2, pp. 14-21. Forme, F.G.L., Genoulaz, V.B. and Campagne, J.P. (2007), “A framework to analyse collaborative performance”, Computers in Industry, Vol. 58, pp. 687-97. 870 Forslund, H. and Jonsson, P. (2007), “The impact of forecast information quality on supply chain performance”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 27, p. 90. Gunasekaran, A., Patel, C. and McGaughey, R.E. (2004), “A framework for supply chain performance measurement”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 87 No. 3, pp. 333-47. Gunasekaran, A., Patel, C. and Tirtiroglu, E. (2001), “Performance measures and metrics in a supply chain environment”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 21 Nos 1/2, pp. 71-87. ¨ ˚ Holweg, M., Disney, S., Holmstrom, J. and Smaros, J. (2005), “Supply chain collaboration: making sense of the strategy continuum”, European Management Journal, Vol. 23 No. 2, pp. 170-81. Ireland, R.K. and Crum, C. (2005), “Supply chain collaboration: how to implement CPFR and other best collaborative practices”, J. Ross Publishing, Fort Lauderdale, FL. Kim, B. and Oh, H. (2005), “The impact of decision-making sharing between supplier and manufacturer on their collaboration performance”, Supply Chain Management, Vol. 10 Nos 3/4, pp. 223-36. Lambert, D.M. and Cooper, M.C. (2000), “Issues in supply chain management”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 65-83. Lambert, D.M. and Pohlen, T.L. (2001), “Supply chain metrics”, International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 12 No. 1, pp. 1-19. Larsen, T.S., Thenoe, C. and Andresen, C. (2003), “Supply chain collaboration: theoretical perspectives and empirical evidence”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 33 No. 6, pp. 531-49. Lee, H.L. (2002), “Aligning supply chain strategies with product uncertainties”, California Management Review, Vol. 44, pp. 105-19. Lee, H.L., So, K.C. and Tang, C.S. (2000), “The value of information sharing in a two-level supply chain”, Management Science, Vol. 46 No. 5, pp. 626-43. McCarthy, T.M. and Golicic, S.L. (2002), “Implementing collaborative forecasting to improve supply chain performance”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 32 No. 6, pp. 431-54. McIvor, R., Humphreys, P. and McCurry, L. (2003), “Electronic commerce: supporting collaboration in the supply chain?”, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Vol. 139, pp. 147-52. Matchette, J. and Seikel, A. (2004), “How to win friends and influence supply chain partners”, Logistics Today, Vol. 45 No. 12, pp. 40-2. Raghunathan, S. (2001), “Information sharing in a supply chain: a note on its value when demand is non stationary”, Management Science, Vol. 47 No. 4, pp. 605-10. Rowat, C. (2006), “Collaboration for improved product availability”, Logistics and Transport Focus, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 18-20.

- 16. SCC (2001), Supply-Chain Operations Reference-Model V5.0, Supply-Chain Council, Atlanta, GA. Supply chain Simchi-Levi, D. and Zhao, Y. (2005), “Safety stock positioning in supply chains with stochastic performance lead times”, Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, Vol. 7, pp. 295-318. Seifert, D. (2003), Collaborative Planning, Forecasting and Replenishment: How to Create a Supply metrics Chain Advantage, AMACOM, Saranac Lake, NY. Simatupang, T.M. and Sridharan, R. (2004a), “A benchmarking scheme for supply chain collaboration”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 9-29. 871 Simatupang, T.M. and Sridharan, R. (2004b), “Benchmarking supply chain collaboration: an empirical study”, Benchmarking: An international Journal, Vol. 11 No. 5, pp. 484-503. Simatupang, T.M. and Sridharan, R. (2005), “The collaboration index: a measure for supply chain collaboration”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 35 No. 1, pp. 44-62. Simatupang, T.M. and Sridharan, R. (2008), “Design for supply chain collaboration”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 401-18. Smaros, J. (2007), “Forecasting collaboration in the European grocery sector: observations from a case study”, Journal of Operations Management., Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 702-16. Stank, T.P., Keller, S.B. and Daugherty, P.J. (2001), “Supply chain collaboration and logistical service performance”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 29-48. VICS (2002), CPFR Guidelines, Voluntary Inter-industry Commerce Standards, available at: www.cpfr.org (accessed January 2007) Yin, R.K. (1994), Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Applied Social Research Methods Series, 2nd ed., Vol. 5, Sage, London. About the authors Dr Usha Ramanathan is a Senior Lecturer in Logistics and Supply Chain Management in Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, UK. Her research interest includes supply chain collaboration, collaborative planning forecasting and replenishment (CPFR), value of information sharing and forecasting, structural equation modeling, simulation, AHP and SERVQUAL. She has published in leading journals such as International Journal of Production Economics, Expert Systems with Applications and Omega: The International Journal of Management Science. Dr Angappa Gunasekaran is a Professor in, and the Chairperson of, the Department of Decision and Information Sciences at the Charlton College of Business, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. He teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in operations management and management science. He has over 190 articles published in 40 different peer-reviewed journals, has presented about 50 papers and published over 50 articles in conferences, and has given a number of invited talks in about 20 countries. Dr Gunasekaran is on the editorial board of over 20 journals. He is the editor of several journals in the field of operations management and information systems. Dr Gunasekaran is currently interested in researching information technology/systems evaluation, performance measures and metrics in new economy, technology management, logistics and supply chain management. He actively serves on several university committees. He is also the Director of the Business Innovation Research Center (BIRC). Dr Nachiappan Subramanian is an Associate Professor at Thiagarajar College of Engineering, Madurai, India. Nachiappan (Nachi) has published over 75 refereed papers which include journal articles and international conference papers. Currently, he is on the editorial board of the International Journal of Integrated Supply Management and International Journal of Applied Industrial Engineering. He also serves as a reviewer for many leading operations

- 17. BIJ and supply chain management journals. In September 2011 he is joining as an associate professor in operations management at the University of Nottingham Ningbo, China. Previously, 18,6 Nachi conducted his post-doctoral research at University of Nottingham, UK, under BOYSCAST fellowship program and received the Australian Endeavour Research Fellowship Award to conduct research on complexity, risks and low-cost country sourcing (with special reference to India). His research interests are supply chain operations, modeling and analysis of manufacturing systems, sustainable supplier selection, low-cost country sourcing, supply chain 872 complexity and resilience and reverse logistics. Nachiappan Subramanian is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: spnmech@tce.edu To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints