Cowenprutttart

- 1. PHILIP A. COWAN AND CAROLYN PAPE COWAN University of California, Berkeley MARSHA KLINE PRUETT Smith College* KYLE PRUETT Yale University School of Medicine** JESSIE J. WONG University of California, Berkeley*** Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children: Preventive Interventions for Low-Income Families Few programs to enhance fathers’ engage- Participants in couples’ groups showed more ment with children have been systematically consistent, longer term positive effects than those evaluated, especially for low-income minority in fathers-only groups. Intervention effects were populations. In this study, 289 couples from similar across family structures, income levels, primarily low-income Mexican American and and ethnicities. Implications of the results for European American families were randomly current family policy debates are discussed. assigned to one of three conditions and followed for 18 months: 16-week groups for fathers, In the U.S. Deficit Reduction Act of 2006, 16-week groups for couples, or a 1-time infor- one third of the $150 million annual budget mational meeting. Compared with families in for family support was allocated to programs the low-dose comparison condition, interven- promoting fathers’ involvement with their tion families showed positive effects on fathers’ children. This unprecedented commitment on engagement with their children, couple relation- the part of government policy makers to ship quality, and children’s problem behaviors. providing father-focused services for families was justified by citations of literature from three sources (see the Administration for Children and Department of Psychology, 3210 Tolman Hall-1650, Families’ Promoting Responsible Fatherhood University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA website: http://fatherhood.hhs.gov/index.shtml). 94720-1650 (pcowan@berkeley.edu). First, some observers (e.g., Blankenhorn, 1995; *Smith College & School for Social Work, 310 Lilly Hall, Popenoe, 1996) describe an increase in fathers’ Northampton, MA 01063. absence and disengagement from the family **School of Medicine, Yale University, 40 Trumbull Road, as a consequence of increases in separations, Northampton, MA 01060. divorces, and single parenthood and conclude ***Department of Psychology, 3210 Tolman Hall-1650, that this has posed serious risks for children’s University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA development and well-being. Second, findings 94720-1650. from the 20-city Fragile Families study of births This article was edited by Ralph LaRossa. to primarily low-income unmarried mothers Key Words: experimental methods, father-child relations, (Carlson & McLanahan, 2002) showed that most Hispanic American, marriage and close relationships, biological fathers have an ongoing romantic parenting, prevention. relationship with the mother when their child Journal of Marriage and Family 71 (August 2009): 663 – 679 663

- 2. 664 Journal of Marriage and Family is born, but many faded from their child’s life conflict resolution, problem-solving styles, and over the next few years. emotion regulation; (d) the quality of the Third, over the past 3 decades, an expand- mother-child and father-child relationships; and ing body of literature concludes that fathers’ (e) the balance between life stressors and social engagement with their children is associated supports outside the immediate family. with positive cognitive, social, and emotional Not surprisingly, fathers are more likely to outcomes for children from infancy to adoles- be engaged in a positive way with their young cence (P. A. Cowan, Cowan, Cohen, Pruett, & children when they have few symptoms of poor Pruett, 2008; Lamb, Pleck, Charnov, & Levine, mental health, are securely attached to their 1985; K. D. Pruett, 2000; Tamis-LeMonda & own parents, communicate effectively with the Cabrera, 2002). Conversely, children of disen- child’s mother, are under less external life stress, gaged or negatively engaged fathers are at risk and have more social support. By contrast, neg- for a host of cognitive, social, and emotional ative events in each of these domains increase difficulties. Father engagement has been defined risks for abuse and neglect of children (Rosen- in many ways but measured primarily in terms berg & Wilcox, 2006). The family systems of quantity of time spent with children, yet stud- model suggests that interventions need to focus ies consistently show that the quality of fathers’ on reducing the multiple risks and enhancing the involvement rather than the sheer quantity of multiple protective factors associated with father contact is associated with positive outcomes for engagement. The present intervention study, children (e.g., Amato, 1998). designed to support fathers’ positive engage- Two quite different explanations have been ment with their young children, addressed all advanced to explain why some fathers are five family domains in the intervention curricula more involved in their children’s lives whereas and focused on changes in father-child rela- others are either less involved or absent. tionships, couple relationships, and children’s A widely accepted deficit model of father outcomes in the assessment protocols. involvement (Hawkins & Dollahite, 1997) assumes that the pervasive social problem of EXISTING FATHER ENGAGEMENT ‘‘fatherlessness’’ in America has resulted from a decline in ‘‘family values’’ and a lack of INTERVENTIONS motivation on the part of men to maintain Before planning the Supporting Father Involve- relationships with their spouse and child ment study, we searched the research literature (Blankenhorn, 1995; Popenoe, 1996). These on interventions to foster fathers’ engagement conclusions underlie interventions designed to (P. A. Cowan et al., 2008; Doherty et al., 1998; persuade men to become ‘‘more responsible.’’ Hawkins, Christiansen, Sargent, & Hill, 1995; By contrast, an ecological (Belsky, 1984; Mincy & Pouncy, 2002). We examined accounts Bronfenbrenner, 1979) or family systems risk- of programs from federal and state governments, protection-outcome model (C. P. Cowan & fatherhood organizations, and family agencies Cowan, 2000; M. K. Pruett, Insabella, & that produced materials providing information Gustafson, 2005) assumes that there are multiple about the importance of fatherhood and the systemic factors—a combination of barriers availability of support services for fathers (e.g., and resources within individuals, families, and http://www.fatherhood.org). More direct inter- environments—that shape both the quantity ventions in the form of single-event contact and quality of fathers’ engagement with their with fathers are described as fatherhood work- children. Our review of the literature suggests shops or mass motivational meetings attended that father engagement is associated with by men, often with an explicitly religious per- risks and protective factors in five aspects of spective (e.g., http://www.promisekeepers.org). family life (see also Doherty, Kouneski, & Other programs have a structure of ongoing con- Erickson, 1998): (a) individual family members’ tact between professional or paraprofessional mental health and psychological distress; (b) the staff and fathers, one by one or in groups. Some patterns of both couple and parent-child family agencies at the local level and national relationships transmitted across the generations Headstart and Early Headstart programs have from grandparents to parents to children; added components that reach out to fathers (c) the quality of the relationship between at home and at center-based programs (http:// the parents, including communication styles, fatherhood.hhs.gov/Parenting/hs.shtml). Home

- 3. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 665 visiting programs for parents of young children no-treatment condition. Outcome assessments have focused almost entirely on mothers, but a at 5 months postpartum revealed a positive few include fathers in their purview. impact on fathers’ warmth and emotional Other family agencies and fatherhood orga- support, intrusiveness, and dyadic synchrony nizations offer ongoing groups for men, led when fathers were observed with their babies. by men, usually meeting up to three or four Compared to fathers in the no-treatment group, times a month, although a few extend over fathers who participated in an ongoing group 3 months. Different programs extending over were more involved with the child on days when time have been addressed to fathers who are they worked outside the home. teens (Klinman, Sander, Rosen, & Longo, Systematic evaluations of father involvement 1986), low-income and single parents (Balti- programs are in a distinct minority, and most pro- more Responsible Fatherhood Project: http:// grams receive no systematic evaluation beyond www.cfuf.org/BRFP), and in married couples documentation of the number and characteris- (Fagan & Hawkins, 2001) and divorced cou- tics of clients served and surveys of consumer ples (Cookston, Braver, Griffin, De Luse, & satisfaction. Reports of these programs, usually Jonathan, 2007). The focus of the meetings on websites rather than in journal publications, varies widely, from addressing men’s individual balance positive testimony from staff and partic- physical and mental health, including substance ipants with sober reflection on the challenges and use and abuse, to parenting motivation, parenting obstacles involved in mounting the program. The skills, and job skills, to a few that attempt to teach few with pre- and postintervention evaluations men relationship skills to enhance collaboration gather data almost immediately after the group with the mothers. Very occasionally, individ- meetings end, so we do not know whether effects ual case management services are provided to are maintained over time. Most important, with supplement group meetings. the exception of several studies cited above, very A handful of university-based programs, few fatherhood intervention programs have been such as Dads for Life for divorced fathers evaluated using a research design with random- (Cookston et al., 2007), Marriage Moments ized assignment to treatment and control condi- (Hawkins, Lovejoy, Holmes, Blanchard, & tions. Without this procedure, it is not possible Fawcett, 2008), and Parenting Together for to determine whether observed changes in the new fathers (Doherty, Erickson, & LaRossa, intervention participants are more positive than 2006), created curricula based on the type of those in similar families without intervention. ecological family systems, risk-outcome model With the exception of the Marriage Moments we described above. Dads for Life groups for and Parenting Together programs that were divorced men, with a curriculum focused heavily designed for couples, almost all father engage- on a cognitive-behavioral approach to managing ment interventions involve men’s participation anger and reducing conflict, had positive effects in programs led by male speakers, counselors, or on fathers’ relationships with their children group leaders. The paradox here is that the single and ex-wives. The Marriage Moments program, most powerful predictor of fathers’ engagement in two middle-class samples, with videos and with their children is the quality of the men’s workbooks added to a monthly home visiting relationship with the child’s mother, regardless program at 3 months postpartum, produced of whether the couple is married, divorced, sep- relatively strong but marginally significant arated, or never married (P. A. Cowan et al., effects on mothers’ views of the men’s 2008, p. 54). In the present study we evaluated engagement in their children’s daily care. It did the relative impact of a father-focused and a not increase relationship satisfaction, the main couple-focused approach by randomly assign- target of the program. The authors speculated ing some participants to an ongoing fathers’ that a group format might have resulted in a group, some to an ongoing couples’ group, and greater direct impact on the marriage and a some to a one-time, low-dose intervention (the stronger indirect effect on father engagement. comparison group). The Parenting Together program conducted a Finally, many fatherhood programs target randomized assignment design with middle class low-income, often minority, participants, but we couples that included a second trimester home know of no systematic data that evaluate whether visit, four group meetings before the birth of a the same program is effective for both low- and first child and four meetings postpartum, or a middle-income participants or for participants of

- 4. 666 Journal of Marriage and Family different ethnic backgrounds. The current study Resource Centers in four California counties evaluated the effectiveness of interventions for (San Luis Obispo, Santa Cruz, Tulare, and fathers, mothers, and children in European Yuba) in primarily rural, agricultural, low- American and Mexican American families who income communities with a high proportion of range from poverty to middle income. Mexican American residents. Newly hired staff in each setting included a project director, two group leaders, two to three case managers, a data THE SUPPORTING FATHER INVOLVEMENT coordinator, and a county liaison who served as PREVENTIVE INTERVENTION a link between the project and the County Health The Supporting Father Involvement study and Human Services administration. followed a sample of predominantly low- At each site, project staff recruited some income families for 18 months in a randomized participants through direct referrals from clinical trial of two variations of a preventive within the Family Resource Centers and most intervention; two thirds were Mexican American participants from other county service agencies, and one third European American. The study talks at community organizational meetings, compared the impact of a 16-week group for ads in the local media, local family fun days, fathers, a 16-week group for couples, and a and information tables placed strategically at low-dose comparison condition in which both sports events, malls, and other community parents attend one 3-hour group session; all public events where fathers were in attendance. interventions were led by the same trained Because the project was conceptualized as mental health professionals who focused on preventive—to help families early in the family the importance of fathers to their children’s formation years before smaller problems become development and well-being. The one-time intractable—the project targeted expectant meeting and the 16-week curriculum for fathers parents and those with a youngest child from and couples’ groups were based on a family birth to age 7. risk model of the central factors that research A brief screening interview administered by has shown are associated with fathers’ positive a case manager assessed whether the parents involvement with their children. met four additional criteria: (a) both partners Because Supporting Father Involvement was agreed to participate; (b) the father and mother conceptualized as a preventive intervention, were biological parents of their youngest families with current open cases of family child and raising the child together, regardless violence were not included in the project. Thus, of whether they were married, cohabiting, we could not measure the interventions’ direct or living separately; and (c) neither parent impact on a reduction in documented child abuse suffered from a mental illness or drug or and neglect. Furthermore, we did not expect alcohol abuse problems that interfered with that a 16-week intervention for this high-risk their daily functioning at work or in caring sample would make substantial alterations in for their child(ren)—determined through a set mental health symptoms, participants’ views of of questions about whether there were mental their parents, and the stressors in their daily or emotional conditions that interfered with lives. On the basis of earlier intervention results the parent’s ability to look after children or using the couples’ group format (C. P. Cowan & work outside the home. If either parent reported Cowan, 2000; P. A. Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, serious problems of this kind, the family was 2005) we expected that the interventions would not offered one of the study interventions but affect three risk factors for child abuse—the referred for other appropriate services. Finally, quality of the father’s relationship with the child, (d) couples were not accepted into the study the quality of the couple relationship, and the if there was a current open child or spousal children’s behavior. protection case with Child Protective Services or an instance within the past year of spousal violence or child abuse. This last criterion METHOD was designed to exclude participants whose increased participation in daily family life might Procedures and Participants increase the risks for child abuse or neglect. The Supporting Father Involvement (SFI) Of 550 couples who were administered project and staff were located within Family a screening interview, 496 (90.2%) met the

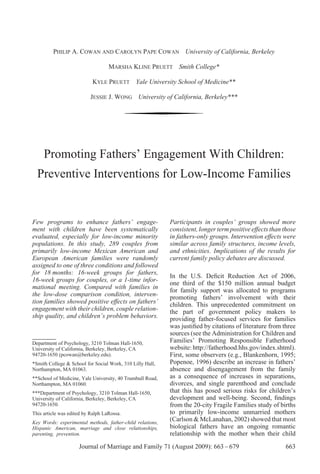

- 5. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 667 criteria for eligibility. (See Figure 1 for a flow the study intervention and in the assessments chart.) Each eligible couple was then scheduled prior to and after the intervention. Of the 496 for a joint 1.5-hour initial interview with the eligible couples, 405 (81.7%) completed the group leaders that covered topics in five initial interview. aspects of family life (individual, couple, parent- Until the interview, the couples were not child, three-generational, life stress, and social aware of the fact that they were about to be support). The interview acquainted couples offered a chance to participate in a randomized with the issues they would be discussing in clinical trial, nor were they aware of which FIGURE 1. RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION. Screening Interviews n = 550 550 couples Eligible n = 496 496 couples Completed Completed Completed Initial Interview Initial Interview Initial Interview Assigned to Assigned to Assigned to n = 405 Low Dose Comparison Fathers' Groups Fathers' Groups 132 couples 130 couples 143 couples Consented to Consented to Consented to Randomization Randomization Randomization n = 397 130 couples 128 couples 139 couples Completed Completed Completed Baseline Baseline Baseline n = 371 124 couples 118 couples 129 couples Completed Completed Completed Post 1 Post 1 Post 1 n = 286 Assessment Assessment Assessment 100 couples 93 couples 93 couples Completed Completed Completed Post 2 Post 2 Post 2 Assessment Assessment Assessment n = 289 98 couples 96 couples 95 couples

- 6. 668 Journal of Marriage and Family condition they would be offered. At the end (Post 1). A second assessment 11 months after of the initial interview, 397 of 405 couples the groups ended or 18 months after they entered agreed to accept random assignment to one the study (Post 2) was completed by 289 cou- of three conditions: a 16-week group for ples (78% of the baseline participants). Parents fathers or for couples or the informational were not paid for attending groups or meetings, one-time meeting (the low-dose comparison but each partner was paid $50 for completing condition described above). All parents were the baseline, $50 for the Post 1 assessment, and then scheduled for individually administered $100 for the Post 2 assessment (a total of $400 1.5- to 2.5-hour baseline assessments, consisting per family over 18 months). of questionnaires administered orally in English or Spanish by one of the site’s case managers. Only 26 of the 397 fathers and mothers failed Fathers’ Groups and Couples’ Groups to complete the baseline assessments. The most After baseline assessments were completed, the common reasons given to case managers for single meetings of the low-dose comparison not carrying through with the initial interview group parents and the 16-week fathers’ and or the baseline assessment were lack of time, couples’ groups began. All groups were led by changes in work schedule making attendance at male-female pairs of mental health professionals group meetings impossible, and lack of interest selected by project directors on the basis in participating. of clinical expertise, training, and experience Of the 371 couples who completed the with couples or groups or both, knowledge baseline assessments, just over two thirds of of family and child development, cultural the participants (67%) were Mexican American, fluency and sensitivity, and the ability to work 27% were European American, and 6% were collaboratively with other professionals and Asian American, African American, Native agencies. American, or mixed race. On entering the study, The groups for 6 to 12 fathers or five to nine 72% of the couples were married and living couples met for 2 hours each week for 16 weeks together, 22% were cohabiting, and 6% were and involved both a structured curriculum of living separately and raising a child together exercises, discussions, and short presentations (separated, divorced, or never-married, never- and an open-ended time in which participants cohabiting couples). Median household income were free to raise their real-life issues and was $29,700 per year, with more than two concerns for discussion and problem solving. thirds of the sample falling below twice the As the study proceeded, some sites conducted Federal poverty line ($40,000 yearly household the interventions with a greater number of income for a family of four). We did not screen participants in their groups and some used a participants for income; although the sample different number of sessions (from 11 to 14), but was heavily weighted toward low incomes, all preserved a total of 32 hours of face to face 2.5% had household incomes between $100,000 meetings between leaders and participants. In and $300,000 per year, which enabled us to total, there were 20 single-session meetings (the examine income level as a potential moderator comparison condition), 15 fathers’ groups, and of intervention effects. 18 couples’ groups. Child care was provided A large majority (79%) of the fathers and each week to allow parents to focus on their a minority (39%) of the mothers had worked family issues for the most part undisturbed. for pay during the week prior to their baseline In all, 21 of the low-dose comparison group assessment. About half of the participants had meetings, fathers’ groups, and couples’ groups completed high school or beyond. At baseline, were conducted in Spanish and 32 in English. the number of children in the household ranged The curriculum is detailed in a manual from 0 (mother was pregnant with a first child) followed by the group leaders. The manual to 7, with a mean of 2.34 children; the median was adapted by Marsha Kline Pruett and age of the youngest child was 2.25 years. Rachel Ebling from the original curricula used The assessments conducted by the case man- in the Cowans’ earlier intervention projects agers were repeated with partners in 286 couples (C. P. Cowan & Cowan, 2000; P. A. Cowan (77% of the baseline participants) 2 months after et al., 2005) in order to accommodate the cultural completion of the ongoing groups or 7 months and linguistic differences and the broader after the one-session informational meeting diversity of family forms represented in this

- 7. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 669 project. With only several modifications to adapt group responses. On a continuum of intervention the fathers’ group curriculum for the absence styles ranging from open-ended group therapy of partners in the room, the curricula for both (Yalom, 1995) to psychoeducational teaching fathers’ and couples’ groups were identical. of specific communication skills (Stanley, Some of the exercises in the couples’ group Blumberg, & Markman, 1999), our approach that involved direct interaction between partners occupies a middle ground. In the open-ended became ‘‘homework’’ for the fathers to try out check-ins and exercises, the leaders do not with their partners between group meetings. attempt to provide solutions to couple or After the first meeting, each subsequent parenting issues, but to draw participants out session involved an open-ended check-in to about their own goals and any impasses related discuss unresolved issues from the last group, to the issue and to encourage their attempts difficulties in completing any homework, and to make headway on them. The structure is positive or negative events occurring during provided by the leaders’ agendas, the selection the week that an individual or couple wanted of exercises and tasks, and active guiding of the to share. The structured part of each meeting group discussions from week to week. was focused on one of the five domains of Given the economic and social hardships our model. Leaders’ questions, exercises, and experienced by many of the participants in games allowed participants to discuss how they this study, we expected that group meetings were feeling about themselves and what they over a 4-month period would not be sufficient wanted to change (e.g., examining discrepancies to maintain families’ participation in the study between their actual and ideal self-descriptions and produce change in all five aspects of the on The Pie), parenting principles (e.g., defining participants’ lives. Thus, all couples in both the and role playing different parenting styles), group intervention and low-dose comparison couple communication exercises (e.g., a ‘‘How conditions received the services of a case well do you know your partner?’’ game), three manager, who was available to make appropriate generational family patterns (e.g., packing a referrals for assistance with individual, family, ‘‘bag’’ to include family rituals to be repeated medical, employment, or legal issues over the or avoided in their current family), and how 18 months of each family’s participation. The to find supports for dealing with life stresses case managers also served as a link to other (e.g., compiling a list of helpful personal and aspects of the study by following up with community resources). Of the 16 meetings, participants when they missed a group meeting 2 were devoted to individual issues, 4 to and maintaining contact with parents in between parenting, 4 to the couple relationship, 2 to the three individual assessments. three-generational issues, and 2 to stresses and supports outside the family. In both fathers’ and couples’ groups, two of the 16 meetings were Measures conducted separately for fathers and mothers Demographic information. Parents were asked (fathers met with the male coleader and focused to describe their age, household composition, on their relationship with their children; mothers number of children, ethnicity, marital status, met with the female coleader and focused on the employment status, income level, and education. process of engaging fathers and sharing family tasks with them). In addition, the mothers were Father-child relationship: Psychological and invited to the first meeting of the fathers’ groups behavioral engagement. The Pie (C. P. Cowan in order to increase the probability that their & Cowan, 1991) was developed to represent partners would participate. individuals’ psychological investment in various The combination of structure and flexibility aspects of their lives. Beside a circle 4 inches in allowed group leaders to maintain lesson plans diameter, they listed the main roles in their life that followed the general model and goals for the right then, and divided the circle (pie) so that groups while using their professional acumen in each section reflected the salience or importance implementation. For example, the leaders could of that aspect of self, not the amount of time choose from an exercise that requires moving spent in the role. A coding scheme from prior around the room and acting out scenarios to content analyses included family roles such as stimulate discussion of an issue or a similar parent and partner/lover; worker and student exercise that involved more storytelling and roles; leisure roles such as artist and gardener;

- 8. 670 Journal of Marriage and Family and ‘‘core’’ aspects of the self such as me or from girls diagnosed as inattentive but not myself alone. In this study, we focus on the size hyperactive (Hinshaw, 2002). (degrees of the circle) labeled father or parent in the pies filled out by the men. Couple relationship quality and stability. The Fathers’ involvement in the daily care of the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI; Norton, children was assessed by a Who Does What? 1983), a six-item questionnaire with one global questionnaire (P. A. Cowan & Cowan, 1990). estimate and five specific questions about marital Each parent rated a number of tasks representing satisfaction, was used to measure each partner’s the division of labor for care of the youngest satisfaction with the couple relationship (α = child (feeding, taking the child to the doctor) .93 for fathers and .94 for mothers). This single- using a 1 − 9 scale in which 1 = she does it all, factor scale has high overlap with longer, more 5 = we do it about equally, and 9 = he does it all. traditional measures of marital quality (Heyman, Item reliabilities at baseline were high (α = .80 Sayers, & Bellack, 1994). for fathers and .81 for mothers). Correlations between fathers’ and mothers’ descriptions at Conflict About Discipline. From the Couple the three assessment points ranged from .62 to Communication Questionnaire (C. Cowan & .74, suggesting that both partners described their Cowan, 1990) we selected one item that division of family labor similarly, though not describes the extent of disagreements between identically. partners about disciplining the child on a scale from 0 (no conflict) to 6 (a lot of conflict). Parenting stress. We measured each parent’s level of distress specifically related to parenting Children’s Behavior Problems. The Child the target child with a 38-item revised version Adaptive Behavior Inventory (P. A. Cowan, (Loyd & Abidin, 1985) of the original 150-item Cowan, & Heming, 1995), a 54-item adapta- Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Parents indicated tion of the 106-item Child Adaptive Behavior the extent of their agreement or disagreement Inventory, was filled out by each parent. This with statements describing themselves as instrument contains items selected from a 60- stressed, their child as difficult to manage, and item Adaptive Behavior Inventory (Schaefer a lack of fit between what they expected and & Hunter, 1983), the downward extension of the child they have (α = .91 for fathers and the Quay-Peterson Behavior Problem Checklist .92 for mothers). The scale has been validated (O’Donnel & Van Tuinen, 1979), and Achen- by comparing parents who do and do not have bach and Edelbrock’s (1983) Child Behavior known stressors in childrearing (children with Checklist (CBL). It contains both positive and developmental delay, oppositional defiance, or negative descriptors of cognitive and social com- difficult temperaments; Abidin, 1997). petence (e.g., ‘‘is smart for his/her age,’’ ‘‘has trouble concentrating on what he/she’s doing,’’ Parenting style attitudes. The Ideas About ‘‘is often sad,’’ ‘‘breaks or ruins things’’). Parenting questionnaire (Heming, Cowan, & Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging Cowan, 1991) combined items from scales by from 1 (not at all like this child) to 4 (very Baumrind (1971), Block (1971), and Cohler, much like this child). To reduce the item-based Grunebaum, Weiss, and Moran (1971). Fathers scales to a manageable number of aspects of and mothers indicated the extent of their own adaptation, we composited the scores into four agreement or disagreement with each item dimensions based on a previous factor analysis and what they believed were their partners’ of the scale (C. P. Cowan & Cowan, 1992): opinions. One of three factors, authoritarian (a) externalizing-aggression; (b) externalizing- parenting, was used in the present study to hyperactivity; (c) internalizing-shy withdrawn; describe punitive parenting with high structure and (d) internalizing anxiety, depression. In and demands for conformity. Although the previous studies (Gottman & Katz, 1989), conceptual consistency of the items was the interitem consistencies of these composite high, item reliability at baseline was modest dimensions filled out by teachers were very high (α = .60 for fathers and .63 for mothers). (alphas in the .80s and .90s) and those filled out The authoritarian parenting scale differentiated by parents were moderate (.60s and .70s). In the parenting in another study of families with girls present study, the alphas for parents’ descrip- with both attention and hyperactivity disorders tions ranged between .71 (hyperactivity) and .85

- 9. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 671 (externalizing-aggression) for both mothers and interactions. A statistically significant Baseline fathers; all of the reliabilities for parents’ ratings measure × Retention interaction, F (15, 299) were higher than those for the corresponding = 3.31, p < .001, was followed by univariate scales in a middle-class sample. Correlations of F tests for each measure. mothers’ and fathers’ descriptions on each of On 3 of the 10 dependent measures, the 82 the four dimensions were consistently moder- couples who completed the baseline but not ate to high at each assessment period; baseline the Post 2 assessment 18 months later were .35 − .45; Post 1 .35. − 54, Post 2, .35 − .53. in more distress at the beginning of the study than the 207 couples who completed the Post 2 follow-up 18 months later. The noncompleters RESULTS initially showed greater parenting stress on First, we present results pertaining to retention the PSI, F (1, 333) = 4.22, p < .05, lower of the participants from their first screening satisfaction with the couple relationship on for eligibility through the second posttest, the QMI, F (1, 333) = 21.20, p < .001, and 18 months after completing the preintervention more conflict about disciplining the child baseline assessments. Second, we examine the on the Couple Communication Questionnaire, impact of fathers’ groups, couples’ groups, F (1, 333) = 8.04, p < .01. There were no significant retention effects as a function and the one-time meeting by examining of fathers’ initial level of involvement in change in the parents and children over time. the daily tasks of child care, psychological Third, we describe our search for potential involvement as a parent as measured by The moderators of the intervention effects—whether Pie, authoritarian ideas about parenting, or either there were different findings depending on the parent’s description of their child on the Child demographic or psychological characteristics of Adaptive Behavior Inventory. Despite the fact the participants. that some of the more distressed participants dropped out, there was a full range of adaptation Factors Affecting Retention scores among the large majority who continued to the end of the study. Our first question was whether retention rates Attendance at the 16-week group meetings differed among those assigned to the single- was quite high. The median attendance in the meeting information condition, a fathers’ group, fathers’ groups was 67%. In terms of range of or a couples’ group. We found no differences in attendance, 9% of the fathers attended every participants in the three intervention conditions meeting (32 hours); 40% attended more than in terms of the proportion of participants 25 hours, 67% more than 19 hours, and 81% retained from condition assignment to baseline more than 13 hours. completion (χ 2 = 1.06, p < .60), from baseline In the couples’ groups, median attendance completion to the completion of Post 1 (χ 2 = was 75% for fathers and 80% for mothers. 1.45, p < .50), or from Post 1 to the completion For fathers, 11% had perfect attendance, 61% of Post 2 (χ 2 = 0.53, p < .80). Neither did attended more than 25 hours, 81% more than χ 2 tests reveal differences in retention rate 19 hours, and 95% more than 13 hours. For among the three conditions as a function of mothers, 18% had perfect attendance, 60% ethnic group membership (Mexican American attended more than 25 hours, 87% more than vs. European American), income (below or 19 hours, and 96% more than 13 hours. Once above federal poverty level), or family status a father or couple attended the first or second (married vs. cohabiting). meeting of the groups, the median attendance A mixed model GLM analysis (Gen- rate was close to 90%. der of parent × Baseline measures × Retention) that included all of the measures reported in The Impact of Participation in the Intervention this study examined whether there were differ- ences at baseline between those who completed Groups or failed to complete the Post 2 assessment. Tables 1 and 2 presents mean scores on the ques- We focus here only on the interaction terms of tionnaires as a function of time (baseline, Post 2), interest to the retention analysis. There were condition (low-dose comparison, fathers’ group, no significant Retention × Gender of parent couples’ group), and gender of parent. Data for

- 10. 672 Journal of Marriage and Family Table 1. Pretest Baseline Means, Standard Deviations, for Time × Condition × Gender Intervention Analyses (N = 289) Pretest Baseline Comparison Fathers’ Group Couples’ Group Father Mother M Father Mother M Father Mother M Parents’ adaptation Psychological involvement M 102 — 104 — 101 — SD 50 48 48 Who Does What? M 3.7 3.4 3.55 3.8 3.4 3.60 3.4 3.2 3.30 SD 0.9 1.1 1.1 1.2 1.0 1.0 Ideas about parenting M 67.7 68.4 68.05 68.4 66.8 67.60 69.0 65.2 67.10 SD 10.8 11.7 11.8 13.7 12.5 12.6 Parenting stress M 66.4 68.4 67.40 68.0 67.3 67.65 72.6 73.2 72.90 SD 17.9 18.4 14.8 18.7 16.3 18.1 Couple satisfaction M 38.2 36.2 37.20 37.0 35.7 36.35 36.7 35.3 36.00 SD 6.0 8.1 6.9 8.1 7.3 7.9 Conflict about discipline M 5.8 5.7 5.75 5.8 5.9 5.85 5.9 5.4 5.65 SD 1.5 1.6 1.6 1.5 1.4 1.7 Children’s adaptation Aggression M 1.74 1.71 1.73 1.68 1.69 1.69 1.78 1.78 1.78 SD 0.5 0.6 0.5 0.6 0.5 0.6 Hyperactivity M 2.04 2.03 2.04 2.02 1.94 1.98 2.11 2.04 2.08 SD 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.7 0.6 0.6 Shy or withdrawn M 0.82 1.00 0.91 1.42 1.23 1.33 1.69 1.08 1.39 SD 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 Anxiety or depression M 1.50 1.42 1.46 1.44 1.43 1.44 1.46 1.41 1.44 SD 0.4 0.4 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.5 the pretest baseline are in Table 1 and for the the interactions of Time × Condition that sig- Post 2 assessment 18 months later in Table 2. nify a significant intervention effect (listed in The data from Post 1 were included in the analy- Tables 1 and 2). In this sample of 572 individ- ses but were not included here, in part for reasons uals (286 couples), the power to detect a small of space and, in part, because all of the post hoc interaction effect size of .25 is .99. Four of the tests focused on longer-term effects from base- 10 measures showed a statistically significant line to Post 2; the Post 1 data are available from Time × Condition interaction, and one showed the first author. a Time × Condition × Gender interaction (see We conducted three-way analyses of vari- Tables 1 and 2). The intervention affected men’s ance (ANOVAs; Time × Condition × Gender) psychological involvement with their children to identify significant intervention effects on (The Pie) and both partners’ views of men’s father engagement, couple relationship quality, involvement in daily childcare tasks (Who Does and child outcomes. These analyses contained all What?), parenting stress (PSI), and satisfaction main effects and two-way and three-way inter- with the couple relationship (QMI). A statis- actions, but, to conserve space, we focus only on tically significant Time × Condition × Gender

- 11. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 673 Table 2. Post 2 Means, Standard Deviations, and F Tests for Time × Condition × Gender Intervention Analyses (N = 289) Post 2 Comparison Fathers’ Group Couples’ Group Father Mother M Father Mother M Father Mother M F T ×C Parents’ adaptation Psychological involvement M 109 — 125 — 115 — 2.48∗ SD 52 61 49 Who Does What? M 3.9 3.5 3.70 4.2 3.8 4.00 3.9 3.7 3.80 2.99∗ SD 1.1 1.1 1.2 1.4 1.1 1.2 Ideas about parenting M 67.8 69.3 68.55 66.8 65.7 67.25 68.0 64.4 66.20 SD 10.9 12.1 11.7 12.8 10.7 11.1 Parenting stress M 68.0 67.4 67.70 66.5 67.2 66.85 70.4 65.1 67.75 3.12∗ SD 17.3 15.8 16.2 17.0 19.4 17.1 Couple satisfaction M 34.0 33.1 33.55 35.0 33.3 34.15 34.9 35.6 35.25 2.78∗ SD 8.4 9.9 8.8 9.0 8.6 8.4 Conflict about discipline M 5.8 5.5 5.65 5.8 5.8 5.80 5.6 5.8 5.70 3.52∗∗ T×C ×G SD 1.4 1.5 1.3 1.2 1.5 1.3 Children’s adaptation Aggression M 1.84 1.82 1.83 1.73 1.75 1.74 1.84 1.82 1.83 SD 0.5 0.4 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 Hyperactivity M 2.17 2.19 2.18 2.06 2.02 2.04 2.13 2.04 2.09 SD 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 Shy or withdrawn M 1.58 2.21 1.90 2.62 1.51 2.07 2.00 1.21 1.61 SD 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.5 0.4 0.4 Anxiety or depression M 1.58 1.52 1.55 1.52 1.53 1.53 1.52 1.48 1.50 SD 0.4 0.4 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.4 ∗p = .05. ∗∗p = .01. interaction revealed that group participants overall change in each condition from baseline reported fewer parental conflicts about discipline to Post 2, because we were interested primarily as reflected in fathers’ but not mothers’ reports in whether any changes could be maintained (Couple Communication Questionnaire). for almost a year beyond the Post 1 follow-up Following these five interaction effects, we conducted shortly after the groups ended. conducted post hoc tests with a Bonferroni We also conducted exploratory post hoc tests, correction for multiple tests to determine the with Bonferroni corrections, on the parents’

- 12. 674 Journal of Marriage and Family descriptions of the child. We realize that the parents used the full range of items and viewed choice to perform post hoc tests when there was a few of the children as high in all problem no statistically significant interaction capitalizes areas. Because the variation in ratings was quite on chance findings, but in a first randomized low, small differences in means were statistically clinical trial of these interventions with low- significant. income families, we thought it important to Compared to the results for the low- identify trends to test in later research. Our dose comparison families over 18 months, choice was further justified by an examination of results were more positive for fathers’ group the mean changes over time across conditions, participants, but still slightly mixed. Gains from which showed a nonrandom pattern of higher baseline to Post 2 were evident in fathers’ increases in problem behavior on aggressive, engagement with children on psychological hyperactive, shy or withdrawn, and anxiety or measures (The Pie, t[87] = 3.78, p < .001); the depressive behaviors in children of the low-dose degrees of the circle labeled father increased controls (.10, .14, .99, .09) than in children from 104◦ to 125◦ of The Pie circle. On of fathers’ group participants (.05, .06, .74, behavioral measures of daily child-care tasks .09) and especially children of couples’ group (Who Does What?), fathers also increased from participants (.05, .01, .22, .06). We interpret 3.60 to 4.00, when a rating of 5 means that the these exploratory post hoc results with caution. tasks are equally shared by the parents, t(87) Because of the absence of gender differences = 3.01, p < .01. In contrast with the low-dose in the interaction tests (with one exception), we comparison participants who reported increases describe the means of fathers’ and mothers’ in children’s problem behavior, mothers and scores included in Tables 1 and 2 as a fathers from families assigned to the fathers’ function of time and condition. The overall groups reported no statistically significant result of couples participating in the low-dose changes in their children’s aggression, 1.69 comparison condition was clear. Despite the fact to 1.74, hyperactivity, 1.98 to 2.04, shy that most parents rated the 3-hour informational or withdrawn, 1.33 to 2.07, or anxiety or meeting as useful, the one-time discussion of depression, 1.44 to 1.53. On the negative side, the importance of fathers’ engagement with both parents from the fathers’ group condition children produced little in the way of benefits. mirrored the significant decline in relationship Comparisons between those parents’ baseline satisfaction over 18 months of mothers and and Post 2 scores revealed no change in fathers’ fathers in the comparison condition (QMI), psychological engagement (The Pie), with a 36.35 to 34.15, t(87) = 3.07, p < .01. nonsignificant increase from 102◦ to 109◦ of With couples’ group participants, as with the circle allocated to the father piece, and those from the fathers’ groups, fathers’ no significant change in the Who Does What? engagement with the children showed significant behavioral measure of involvement in child- increases over time on both psychological care tasks, with a small increase from 3.55 engagement, 101◦ to 115◦ of The Pie circle, to 3.70 on a 1−9 scale averaged across 11 t(76) = 1.99, p < .05, and behavioral measures, daily child-care tasks. Furthermore, baseline to 3.30 to 3.80 on the 9-point scale, t(92) Post 2 changes revealed statistically significant = 4.35, p < .001. As with fathers’ group negative changes in 4 of 10 measures for participants, parents’ descriptions of their the low-dose comparison participants. Couple children’s problem behavior remained relatively relationship satisfaction declined from 37.20 to stable over 18 months, aggression 1.78 to 1.83, 33.55, t(94) = 3.46, p< .001, and children’s hyperactivity 2.08 to 2.09, shy or withdrawn problem behavior increased as perceived by 1.39 to 1.61, and anxiety or depression 1.44 parents—aggression, 1.73 to 1.83 t(94) = 2.04, to 1.50. There were two additional noteworthy p < .05, hyperactivity 2.04 to 2.18, t(94) = benefits of participating in a couples’ group. 2.45, p < .01, shy or withdrawn, .91 to 1.90, For both mothers and fathers, parenting stress t(94) = 2.35, p < .05, and depression or anxiety declined significantly, t(91) = 3.79, p < .001, 1.46 to 1.55, t(94) = 2.34, p < .05. We should 72.90 to 67.75, and satisfaction with the couple note that on the average, the parents tended to relationship remained stable over 18 months, describe their children as low in problems—all 36.35 to 35.25. Given the high statistical power of the scales ranged from ratings of 1 (not at to detect differences, we believe that these are all like) to 4 (very much like). Nevertheless, reliable findings. One additional finding was

- 13. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 675 mixed for parents in the couples’ groups: At DISCUSSION Post 2, the fathers reported a significant decline Systematic evaluations of father involvement in conflict and disagreement with the mothers interventions are rare, randomized clinical trials over disciplining their child since baseline, 5.9 are scarce, especially in primarily low-income to 5.6 on a 1 – 7 scale, t(92) = 1.97, p < .05, and non-White populations, and the comparison whereas mothers reported a significant increase of interventions for fathers alone or for fathers in the couple’s conflict about discipline, t(92) and mothers together is unique to this study. The = 2.23, p < .05, 5.4 to 5.8. Perhaps the men Supporting Father Involvement interventions experienced less conflict, whereas the women produced positive results in terms of families’ experienced more disagreement as they engaged retention in the program and parents’ and in increased discussion of childrearing issues. children’s well-being, results that appear to be Some of the mean changes in measures generalizeable to families from several different reported above appear to be quite small, but backgrounds and income levels. of course they reflect only the average scores of participants in each condition. Some of the low-dose control participants made much larger Retention shifts in a negative direction, whereas some participants of the fathers’ and couples’ groups There were no selection effects in this study managed to make important changes in their based on the experimental conditions to which relationships as couples and with their children, participants were randomly assigned. Although significantly more participants with initially high or at least to stave off the normative declines that parenting stress, couple relationship dissatis- occur over time without intervention. Overall, faction, and disagreements about childrearing the significant t tests evaluating change from dropped out after completing the baseline assess- baseline to Post 2 ranged from 1.99 to 3.79. ments, there was a full range of scores among These results are based on effect sizes equivalent the large majority who continued to the end of to Cohen’s d statistics ranging between .40 and the study. The high retention rate from the base- .79, indicating moderate to large changes in line assessment over 18 months (76%) and high the intervention participants over an 18-month attendance over the 11 to 16 weeks of meetings period. is a testament to the attractiveness of the services to the participants, the skill of the group lead- Moderator Analyses ers, and the diligent work of the case managers in supporting participants’ continuation through In separate three-way ANOVAS (Moderator × regular contact and referrals to other services. Time × Condition) we examined whether the intervention effects were different for par- ticipants who were initially higher or lower Impact of the Interventions in income, married or cohabiting, Mexican Fathers’ groups and couples’ groups. A American or European American, and satisfied randomized clinical trial of a preventive or dissatisfied with their couple relationship. For intervention in the form of a 16-week group for the continuous variables (income, relationship fathers or for couples, led by the same trained satisfaction) dichotomous variables were cre- mental health professionals, showed significant ated from above- or below-median scores. In this gains for participants in both types of groups—in sample of 572 individual parents (286 couples), terms of fathers’ engagement in the care of their the power to detect a small interaction effect size young children and their growing sense of self of .25 is .98. None of the factors that we tested as fathers. in separate ANOVAs qualified as a moderator Participation in a fathers’ or couples’ of the intervention effects; the positive interven- group was associated with stable levels of tion results held across participants who were children’s problem behaviors as the parents low- and higher income, married and cohabiting, perceived them over 18 months compared with and Mexican American and European American, consistent increases in problem behaviors in suggesting that the intervention is quite robust children of parents in the low-dose comparison and generalizeable within the parameters of our condition. We have stated that these results study. were derived from post hoc analyses, despite

- 14. 676 Journal of Marriage and Family the fact that the Time × Condition interactions a representative sample of families in the four were not statistically significant. The fact California counties. The participants were men that this pattern was observed in all four and women willing to consider taking part in measures of child behavior argues against an intervention to enhance fathers’ involvement the interpretation that the findings were in family life. Second, the measures reported random. In the absence of intervention effects here rely on parent reports. We have obtained on parenting ideas and without measures videotaped interactions between mother and of observed parenting behavior, we cannot child and father and child at the follow-up conclude that intervention-induced changes in 11 months after the intervention ended. We more effective parenting were responsible for are now in the process of developing coding the child behavior outcomes. Possibly, the systems relevant to both Mexican American parents’ experience of the groups themselves, and European American families with children the discussions of children’s development, and of varying ages. Third, we have examined the relatively greater couple satisfaction and intervention effects only in Mexican American couple communication combined to protect and European American families. It remains the children against the rise in aggression, to be seen whether Latino families in other hyperactivity, depression, and shy or withdrawn locales and members of other ethnic groups behaviors reported by parents in the low-dose will benefit from these interventions. We have a comparison condition. trial underway at a fifth site in a predominantly Although the curricula for both fathers’ African American community, and adaptations and couples’ groups contain almost identical for other populations are currently under units that focus on the couple relationship, consideration. Fourth, our intervention approach the participants in the couples’ groups were was intended to provide a safe environment the only ones to maintain satisfaction with for fathers and couples to explore how they their relationships as couples over the period want to strengthen their relationships as parents of the study—a finding that runs counter to and partners, rather than to learn specific well-established normative downward trends skills that suggest ‘‘right’’ answers to deal in satisfaction for parents with children from with complex family issues. This approach birth through adolescence (Twenge, Campbell, left room for cultural variations within and & Foster, 2003). Given the similarity of the between intervention sites, one that could curricula, we conclude that the format in which provide a culturally sensitive framework for both partners were present had a specific impact intervention in other ethnic groups. Whether on the couple domain. Although this was not other intervention approaches could produce psychotherapy per se, the therapeutic effects of even better results remains to be tested having both key players and their dynamics in empirically. the room provided a more salient opportunity for Like many randomized clinical trials, ours reinforcing change between as well as within the involved multiple variables in the contrast partners. This is consistent with the fact that the between a low-dose comparison and more parents from the couples’ groups, but not those intensive intervention conditions. From our from the fathers’ groups, also showed significant own observations and the testimony of the declines in parenting stress. In light of the parents, we infer that the group format had a context of this study as an effort to prevent child powerful, normalizing, and supportive effect on abuse, this is a particularly welcome finding, the participants (see Hawkins et al., 2008, who because parents’ stress, irritability, and feelings failed to find a couple relationship effect in a of being ineffective as parents and children’s program administered to individual couples at problem behaviors are key risk factors for child home). maltreatment (Haskett, Ahern, Ward, & Allaire, The interventions did not affect parenting 2006). attitudes as we assessed them. It is possible that the null findings reflect the modest reliability of the items. Before concluding that the Limitations and Next Steps intervention did not affect parenting behavior, There are a number of limitations to the present we must complete our analysis of videotaped study. First, like any intervention study, we father-child and mother-child interactions from recruited a sample of convenience rather than the final follow-up.

- 15. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 677 Finally, because this study has been funded or with couples but, in either approach, how to by the Office of Child Abuse Prevention as a involve both parents in the intervention program. prevention project, open cases of abuse and The most salient policy questions, pending neglect were referred out. This makes it a further positive outcomes from additional challenge to demonstrate that the interventions studies, is whether this type of intervention are effective in preventing child abuse, at could feasibly be brought to scale in a climate least in the short run. What we do know, of decreasing government resources or whether consistent with our risk model, is that the positive the intensity and staffing levels could be reduced effects of the fathers’ groups and couples’ to make it less costly without sacrificing its groups involved improvements in family risk effectiveness. To address the practical issues and protective factors (father engagement, of whether fewer resources could produce the parenting stress, couple relationship quality, and same effects, studies must vary features of the children’s problem behavior) that are known intervention systematically—risk status of the to be associated with problematic outcomes for participants, leader qualifications, number of children such as emotional distress, child abuse, contact hours, the contribution of case managers, and neglect (Cicchetti, Toth, & Maughan, 2000). compensation to participants, and the provision of food and child care during group meetings. Given the complexity of the issues raised in Policy Implications our bimonthly telephone consultations with the staff, we doubt that leaders with less experience The results of this randomized clinical trial are could handle the individual and couple distress relevant to discussions of current attempts at the that often spills over into the group process federal and state level to foster positive father as effectively as our experienced clinicians engagement and healthy family relationships. did. Could the program be administered in Given the caveats listed above—that this is a fewer sessions? We know that one meeting single study of two ethnic groups—we have was not sufficient to produce positive results. shown that our intensive preventive intervention We know that 11 to 16 meetings with a total constitutes an evidence-based practice that can of 32 hours were effective. We do not have increase fathers’ engagement with their children systematic information about the time point at and buffer the normatively expected decline which additional hours stop producing positive in couple relationship satisfaction. Despite gains. We were not able to examine self-selected the caveats, we should not underestimate the dosage effects because there was very little importance of the finding that the interventions variability in attendance at the low end of the were equally successful in both ethnic groups continuum; participants who came to very few and for cohabiting and married couples at lower sessions tended to be the ones who dropped and higher income levels. out of the study, so we could not analyze their The findings from this study further suggest baseline-to-postintervention changes. that interventions involving a single meeting We believe that a program like Supporting with participants are unlikely to have a positive Father Involvement could be mounted on a larger effect. Of course, this remains to be tested with scale if it could be embedded within existing other single-meeting formats and curriculum service delivery systems—Family Resource content. The results also suggest that a curricu- Centers, hospitals, mental health centers, lum that focuses on the risk and protective factors schools, other community agencies such as in multiple aspects of family life was successful the YMCA, or faith-based organizations—with in producing positive changes in the quality of trained family service providers. In the absence both father-child relationships and, when moth- of new funds for additional staff, existing staff ers participated fully as part of the couples’ might be convinced to take on such a program if groups, in maintaining both partners’ relation- they believed that this evidence-based practice ship satisfaction. In addition, we learned that could substitute for parenting classes or family engaging fathers in a fathers’ group was facili- programs that they offer now. The argument tated when the mothers came to the first meeting would be more compelling if we could show with the fathers and attended two additional that the program was able to prevent future meetings with the other mothers. That is, the family distress with its associated increase in question is not whether to intervene with fathers programmatic costs. Plans are underway for

- 16. 678 Journal of Marriage and Family a formal cost-benefit analysis of the current Cohler, B. J., Grunebaum, H. U., Weiss, J. L., & study to determine whether this argument can be Moran, D. L. (1971). The childcare attitudes of two supported empirically. generations of mothers. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 17, 3 – 17. Cookston, J. T., Braver, S. L., Griffin, W. A., De Luse, S., R., & Jonathan, M. (2007). Effects of the Dads NOTE for Life intervention on interparental conflict and This study has been funded by a contract with the coparenting in the two years after divorce. Family California Department of Social Services, Office of Child Process, 46, 123 – 137. Abuse Prevention (OCAP), Teresa Contras, Bureau Chief. Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1990). Couple The authors thank Linda Hockman from OCAP for her Communication Questionnaire. Berkeley: Institute initial shepherding of the project and Latifu Munirah for of Human Development, University of California. her guidance. Thanks also to Mitra Rahnema for her Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1991). The Pie. In 2 years of data management, Peter Gillette for his analysis contributions, the dedicated staff at the four intervention M. S. J. Touliatos, B. F. Perlmutter, & M. A. sites, and the families who gave so generously of their time Straus (Eds.), Handbook of family measurement and effort over the project period. Finally, we thank the techniques (pp. 278 – 279). Newbury Park, CA: loyal undergraduate students at UC Berkeley who worked Sage. diligently to enter these data. Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1992). When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. New York: Basic Books. Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2000). When partners REFERENCES become parents: The big life change for couples. Abidin, R. R. (1997). Parenting Stress Index: A Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. measure of the parent-child system. In C. Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (1990). Who Zalaquett & R. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating stress: does what? In J. F. Touliatos, B. F. Perlmutter, & a book of resources (pp. 277 – 291). Lanham, MD: M. a. Straus (Eds.), Handbook of family measure- Scarecrow Press. ment techniques (pp. 447 – 448). Thousand Oaks, Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual CA: Sage. for the Child Behavior Checklist. Burlington, VT: Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Cohen, N., Pruett, Queen City. M. K., & Pruett, K. (2008). Supporting fathers’ Amato, P. R. (1998). More than money? Men’s engagement with their kids. In J. D. Berrick & N. contributions to their children’s lives. In A. Booth Gilbert (Eds.), Raising children: Emerging needs, & A. C. Crouter (Eds.), Men in families: When do modern risks, and social responses (pp. 44 – 80). they get involved? What difference does it make? New York: Oxford University Press. (pp. 241 – 278). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., & Heming, G. (1995). Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental Manual for the Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory authority. Developmental Psychology Mono- (CABI). Unpublished manuscript, University of graphs, 4, 1 – 103. California, Berkeley. Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., & Heming, G. (2005). process model. Child Development, 55, 83 – 96. Two variations of a preventive intervention for Blankenhorn, D. (1995). Fatherless America: Con- couples: Effects on parents and children during fronting our most urgent social problem. New the transition to elementary school. In P. A. York: Basic Books. Cowan, C. P. Cowan, J. Ablow, V. K. Johnson, & Block, J. (1971). Lives through time. Berkeley, CA: Bancroft Books. J. Measelle (Eds.), The family context of parenting Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human in children’s adaptation to elementary school. development: Experiments by nature and design. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Doherty, W. J., Erickson, M. F., & LaRossa, R. (2006). Carlson, M., & McLanahan, S. S. (2002). Father An intervention to increase father involvement involvement, fragile families, and public policy. In and skills with infants during the transition to C. Tamis-LeMonda & N. Cabrera (Eds.), Hand- parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, book of father involvement: Multidisciplinary per- 438 – 447. spectives (pp. 461 – 488). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Doherty, W. J., Kouneski, E. F., & Erickson, M. F. Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. L., & Maughan, A. (1998). Responsible fathering: An overview and (2000). An ecological-transactional model of child conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and maltreatment. In A. J. Sameroff, M. Lewis, & the Family, 60, 277 – 292. S. M. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of developmental Fagan, J., & Hawkins, A. J. (Eds.). (2001). Clin- psychopathology (2nd ed., pp. 689 – 722). New ical and educational interventions with fathers. York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Clinical Practice Press.

- 17. Promoting Fathers’ Engagement With Children 679 Gottman, J. M., & Katz, L. F. (1989). Effects of marital Mincy, R., & Pouncy, H. (2002). The responsi- discord on young children’s peer interaction and ble fatherhood field: Evolution and goals. In health. Developmental Psychology, 25, 373 – 381. C. S. Tamis-LeMonda & N. J. Cabrera (Eds.), Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., & Allaire, Handbook of father involvement: Multidisci- J. C. (2006). Factor structure and validity of the plinary perspectives (pp. 555 – 597). Mahwah, NJ: Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. Journal of Erlbaum. Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A 302 – 312. critical look at the dependent variable. Journal Hawkins, A. J., Christiansen, S. L., Sargent, K. P., & of Marriage and the Family, 45, 141 – 151. Hill, E. J. (1995). Rethinking fathers’ involvement O’Donnel, J. P., & Van Tuinen, M. V. (1979). Behav- in child care: A developmental perspective. In ior problems of preschool children: Dimensions W. Marsiglio (Ed.), Fatherhood: Contemporary and congenital correlates. Journal of Abnormal theory, research, and social policy (pp. 41 – 56). Child Psychology, 7, 61 – 75. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Popenoe, D. (1996). Life without father: Compelling Hawkins, A. J., & Dollahite, D. C. (1997). Generative new evidence that fatherhood and marriage are fathering: Beyond deficit perspectives. Thousand indispensable for the good of children and society. Oaks, CA: Sage. New York: Martin Kessler Books. Hawkins, A. J., Lovejoy, K. R., Holmes, E. K., Pruett, K. D. (2000). Fatherneed: Why father care is Blanchard, V. L., & Fawcett, E. (2008). Increasing as essential as mother care for your child. New fathers’ involvement in child care with a couple- York: Free Press. focused intervention during the transition to Pruett, M. K., Insabella, G. M., & Gustafson, K. parenthood. Family Relations, 57, 49 – 59. (2005). The Collaborative Divorce Project: A Heming, G., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (1991). court-based intervention for separating parents Ideas about parenting. In M. S. J. Touliatos, B. with young children. Family Court Review, 43, F. Perlmutter, & M. A. Straus (Eds.), Handbook 38 – 51. of family measurement techniques (pp. 362 – 363). Rosenberg, J., & Wilcox, W. B. (2006). The Newbury Park, CA: Sage. importance of fathers in the healthy development Heyman, R. E., Sayers, S. L., & Bellack, A. S. of children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of (1994). Global marital satisfaction versus marital Health and Human Services, Administration for adjustment: An empirical comparison of three Children and Families. measures. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, Schaefer, E. S., & Hunter, W. M. (1983, April). 432 – 446. Mother-infant interaction and maternal psychoso- Hinshaw, S. P. (2002). Preadolescent girls with cial predictors of kindergarten adaptation. Paper attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Back- presented at the Society for Research in Child ground characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and Development, Detroit, MI. social functioning, and parenting practices. Jour- Stanley, S. M., Blumberg, S. L., & Markman, H. J. nal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, (1999). Helping couples fight for their marriages: 1086 – 1098. The PREP approach. In R. Berger & M. T. Hannah Klinman, D. G., Sander, J. H., Rosen, J. L., & Longo, (Eds.), Preventive approaches in couples therapy K. R. (1986). The Teen Father Collaboration: (pp. 279 – 303). Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel. A demonstration and research model. In A. B. Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Cabrera, N. (Eds.). (2002). Elster & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Adolescent fatherhood Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary (pp. 155 – 170). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Lamb, M. E., Pleck, J. H., Charnov, E. L., & Levine, J. Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. A. (1985). Paternal behavior in humans. American (2003). Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A Zoologist, 25, 883 – 894. meta-analytic review. Journal of Marriage and Loyd, B. H., & Abidin, R. R. (1985). Revision of Family, 65, 574 – 583. the Parenting Stress Index. Journal of Pediatric Yalom, I. D. (1995). The theory and practice of group Psychology, 10, 169 – 177. psychotherapy (4th ed.). New York: Basic Books.