Blavatnik

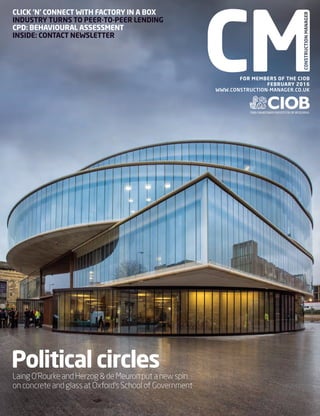

- 1. Political circlesLaingO’RourkeandHerzog&deMeuronputanewspin on concrete and glass at Oxford’s School of Government CLICK ‘N’ CONNECT WITH FACTORY IN A BOX INDUSTRY TURNS TO PEER-TO-PEER LENDING CPD: BEHAVIOURAL ASSESSMENT INSIDE: CONTACT NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS OF THE CIOB FEBRUARY 2016 WWW.CONSTRUCTION-MANAGER.CO.UK BLAVATNIKSCHOOLOFGOVERNMENTCONSTRUCTIONMANAGER|FEBRUARY2016|WWW.CONSTRUCTION-MANAGER.CO.UK 01_CM.Feb16_COVERfinal.indd 1 18/01/2016 15:07

- 2. 30 | FEBRUARY 2016 | CONSTRUCTION MANAGER TechnicalEnvelope Herzog & de Meuron’s Blavatnik School of Government presented huge strategic challenges, but Laing O’Rourke applied offsite techniques on a unique landmark with an innovative glazed facade. Tom Ravenscroft reports POLITICAL CORRECTNESS 30_34.CM.FEB16.Blavatnik.indd 30 18/01/2016 16:32

- 3. CONSTRUCTION MANAGER | FEBRUARY 2016 | 31 TechnicalEnvelope Opposite and above: The building’s form is expressed as a series of stacked discs, with a D-shape breaking out at first-floor level “This is not your typical LaingO’Rourke approach” MikeMorris, LaingO’Rourke market, the school’s lofty ambition is to train the world’s future leaders. Given this aim, it is not surprising that the university desired a piece of statement architecture. Following the US academic funding model, a wealthy donor – in this case controversial international businessman and investor Leonard Blavatnik, the UK’s richest man – was enticed to pay for the building and Swiss architect Herzog & de Meuron commissioned to design it. The practice has designed a distinctive and impressive building. The Blavatnik’s new six-storey home piles unevenly stacked discs that diminish in size and recede from the main road. Transparency is an important concept for the school, which is fully glazed, with each of the discs wrapped in a double-layered glazed skin (see box, p33). Internally, the heart of the 8,000 sq m building is an extremely generous full-height atrium, or forum space, from which it derives its form. The building’s unique geometry, with several cantilevers and no two floorplates alike, as well as plentiful exposed concrete completed to the extremely high level of finish demanded by both architect and client, meant this was a daunting commission. To deliver this high-profile building, the University of Oxford entrusted its long-term collaborator Laing O’Rourke. Over the course of the past 15 years the contractor has completed 11 buildings for the client, including both the £11m student accommodation block for Somerville College that stands next to the new school of government and the £70m Mathematical Institute behind it. This was a relationship that Mike Morris, Laing O’Rourke’s project director, was keen to continue by demonstrating the contractor’s skills on the challenges of the Blavatnik School, although initially his boss did not agree. “When I told Ray [O’Rourke, the group executive chairman] that we wanted to bid for this project with its in-situ frame, he was obviously surprised, as this is not your typical Laing O’Rourke approach,” says Morris. Over the past decade the contractor’s well-publicised focus, backed by substantial investment, has been its offsite construction capability, aka its Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) methodology. Many of its recently completed high-profile schemes, including the Crick Institute and the Leadenhall Building in London, make extensive use of prefabricated elements, as does the Department of Earth Sciences completed for the University of Oxford in 2010. However, at the Blavatnik the use of offsite manufacturing was limited by the building’s unique shape. The school had been a point of controversy long before Laing O’Rourke got involved, with questions asked over the suitability of the sponsor and the scale of the building. Although the modern design was deemed by some to be unsympathetic to the area and the neoclassical Oxford University Press building opposite, the main bone of contention was the building’s height. In central Oxford, buildings within 1.2km of St Martin’s Tower, popularly called the Carfax Tower, are prevented from exceeding 18.2m, while the school of government is 22m high. However, there have been previous exceptions – most notably the 29.6m copper-clad stepped spire of the Saïd Business School, funded by Saudi-Syrian billionaire Wafic Saïd. TAKING ON A BESPOKE starchitect-designed building with a complex geometry that in effect rules out the large-scale use of off-site manufacturing goes directly against Laing O’Rourke’s established company culture. Yet, in Oxford, the contractor has pulled off just that in constructing a landmark £30m building with an in-situ fair-faced concrete frame for the newly established Blavatnik School of Government. One of a new breed of buildings designed to assist the university to compete in the global higher education > Section Section showing floor functions 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Library 5. Teaching 2. Library 6. Entrance/café 3. Academic 7. Teaching 4. Academic 8. Plant LAINGO’ROURKE JOHNCAIRNSHERZOG&DEMEURON 30_34.CM.FEB16.Blavatnik.indd 31 18/01/2016 16:32

- 4. 32 | FEBRUARY 2016 | CONSTRUCTION MANAGER TechnicalEnvelope “In verified views we demonstrated that the quality of the building would improve the views across Oxford” DavidOakey,UniversityofOxford According to David Oakey, the client’s in-house project manager, the university argued that here too the rule should be broken because of the building’s quality: “In verified views we demonstrated that the quality of the building would improve the views across Oxford. Of course having the Herzog & de Meuron name helped with this.” On a more practical note, the university pointed out to planners that for many years buildings in central Oxford have been rising taller than the Carfax height, which only restricts occupied floor height, by placing plant on their roofs. At the school the majority of plant was placed in on a design and build contract and the first time that the architect had been novated,” he explains. “Their concern was that we would dumb down the design, so there was tension at the early stages. But once a price was agreed, which took six months, and confidence levels were established that we were going to deliver a quality project, all went well.” The component the architect was most concerned with was the fair-faced concrete walls, columns, soffits and staircases that could have no obvious joints or surface mounting of services. This concrete would be visible throughout the building, and the project’s success depended on its quality. Herzog & de Meuron requested light- coloured concrete that they had seen in London, however, due to variance in aggregate available locally, this would have cost five times as much in Oxford. As a solution, ground granulated blast- furnace slag (GGBS) was used in the concrete mix to achieve a lighter colour, though it took longer to gain structural strength. To achieve a lightness and colour consistency that satisfied the architect, client and contractor, numerous test pours were carried out, the largest of which was a one-to-one scale section of the building that was the size of a house. “The very high specification of the concrete for the frame, along with the integration of the M&E, made this an extremely challenging pour,” says Steve Holland, the contractor’s project leader. “We invested cost in going through a thorough process to de-risk the pour as much as possible. There was no room for error – we had to get it right the first time.” Laing O’Rourke’s specialist concrete division Expanded Structures has certainly achieved an extremely high quality of finish, of which Holland is rightfully proud. “How do you like our concrete?” he asks as we tour the building. “The in-situ frame goes against our company culture,” he explains, “but we looked at everything and the project couldn’t be built using offsite Above and right: A generous full- height atrium space, displaying the light- coloured concrete specified by Herzog & de Meuron, gives the building its form > the basement so that the space above ground could be fully exploited, and the roof left uncluttered. With planning secured, the university was keen to get the building complete as quick as possible. “Strategically, from the university’s point of view we were a year behind where we wanted to be, so there was a real drive to get the building open for 2015/16,” says Oakey. According to Morris, Laing O’Rourke won the two-stage tender to build the project because of its approach to delivery and, perhaps more importantly, its interface with the design team: “This is the first time that Herzog & de Meuron had worked JOHNCAIRNS 30_34.CM.FEB16.Blavatnik.indd 32 18/01/2016 16:32

- 5. CONSTRUCTION MANAGER | FEBRUARY 2016 | 33 TechnicalEnvelope A breath of fresh air: ventilation and visibility Innovative double-skin glazing opens up the building practically and metaphorically According to architect Herzog & de Meuron, the principles of openness, communication and transparency were central to the challenge of building a school of government. Along with the building’s central forum, the continuous glazed facades are the main architectural gesture that promotes these ideals. Each of the building’s floors is expressed as an individual disc of concrete and glass, with the first floor forming a D-shape. Above the ground floor, each of the discs is wrapped in a double skin that consists of two glazed facades separated by a 750mm gap. The double-glazed inner skin, which was manufactured by Austrian specialist manufacture due to its complex geometry. What we tried to do was approach in-situ with a DfMA culture.” Although the frame itself could not be constructed offsite, Laing O’Rourke was determined to use offsite techniques where possible, so did the next best thing. All of the formwork for the concrete was digitally modelled and manufactured in a controlled environment offsite before being assembled onsite. “Using CAD/CAM to cut the joinery by robot gives us absolute control over the geometry and allows us to create complex forms very accurately,” says Holland. Above and right: The outer layer of broken glazing allows fresh air to circulate around the inner facade facade contractor Waagner-Biro, acts as the primary facade, making the building watertight and providing its thermal envelope. This was manufactured offsite as a panelised system. The permeable outer skin is formed from 600mm wide panes of single glazing separated by 30mm air gaps that allow fresh air to circulate within the void. These panes are supported between prefabricated moulded limestone aggregate concrete sills and heads manufactured by Laing O’Rourke’s DfMA company Explore Manufacturing. These concrete units, which had their fixing system integrated at the production facility, are hung from the building’s frame, with each sill and head supporting four glazed panes. The initial design required around 40 different-sized lintels to be constructed. However, Laing O’Rourke rationalised the design so the 458 concrete sections were built in just nine predominant unit sizes with five specials. The double facade plays an important part in the environmental strategy of the building, which is set to achieve a BREEAM excellent rating. It creates a micro-climate between the skins that assists the natural cooling and heating, and provides extra solar gain and acoustic protection. The fact that the outer glazed facade is permeable to the elements also plays a major role in environmental control, especially for the > cellular offices that occupy the majority of the perimeter spaces on the upper floors. Each office is naturally ventilated with full-height openable panels set within the inner glazing system: the presence of the outer layer removes any risk of accidental falls. Floor to ceiling vents cool the room in summer more efficiently than a high- level opening vent, as the office’s entire temperature gradient is impacted. The window openings can be operated manually or by the Building Management System (BMS), which also controls the intelligent blinds that ensure the building does not overheat. These fabric blinds are on the exterior of the inner glazing, protected by the outer skin. To ensure that there was no confusion on site, the contractor decided not to differentiate between concrete sections that would or would not be visible. “We made the decision to treat all the concrete on the project as fair-faced; this reduced risk, but increased cost,” says Holland. This choice meant that the entire lower basement level, which will never be seen by students or staff, was built with fair- faced concrete, effectively acting as a full- scale final test pour. Constructing areas of the building that were not intended to be on show to the same high standard also has the benefit of increasing flexibility, These concrete units, which had their fixing system integrated at the production facility, are hung from the building’s frame, with each sill and head supporting four glazed panes. The initial design required around 40 different-sized lintels to be constructed. However, Laing O’Rourke rationalised the design so the 458 concrete sections were built in just nine predominant unit sizes with five specials. The double facade plays an important part in the environmental strategy of the building, which is set to achieve a BREEAM excellent rating. It creates a micro-climate between the skins that assists the natural cooling and heating, and provides extra solar gain and acoustic The fact that the outer glazed facade is permeable to the elements also plays a major role in environmental control, especially for the does not overheat. These fabric blinds are on the exterior of the inner glazing, protected by the outer skin. 1 2 3 4 1. Prefabricated concrete head 2. Double-glazed inner skin 3. Glazed outer skin 4. Prefabricated concrete sill JOHNCAIRNS LAINGO’ROURKE 30_34.CM.FEB16.Blavatnik.indd 33 18/01/2016 16:32

- 6. 34 | FEBRUARY 2016 | CONSTRUCTION MANAGER TechnicalEnvelope as spaces can be repurposed without the university having to add any retrospective finishes. A much-trafficked print cupboard that we passed, for example, was originally intended to be storage. The only element that was not poured in-situ was the rear spiral staircase. Although this was originally planned to be in-situ, the complexity of the pour meant Laing O’Rourke had to revert to plan B and insert three precast sections. M&E provision further complicated the concrete pour as the majority of the wiring containment needed to be cast into the structure. To achieve the accuracy needed first time, Laing O’Rourke’s in-house M&E engineer, Crown House Technologies, digitally modelled the containment using GPS coordinates for all junction locations. Access to this M&E had to be through the floor, as all internal ceilings were unbroken concrete, which caused issues between designer and contractor. Herzog & de Meuron initially wanted solid oak flooring throughout the building. An agreement was reached that in the offices, which are more susceptible to change, carpet tiles would be specified. However, the major primary services run below the corridors where oak flooring was used, and this required access panels. “It would have been an absolute nightmare if there had been timber flooring everywhere, due to all the services being under the floor – having carpets in the offices was the sensible thing to do,” says Laing O’Rourke’s Morris. “We originally estimated 600 access panels in the common areas. We got this down to 300, which the architect accepted.” The contractor tried to use DfMA elements wherever possible. Around the concrete frame the building is wrapped in a glazed double skin, with concrete sills and lintels. These elements were manufactured offsite at Laing O’Rourke’s Explore Industrial Park in Steetley, Nottinghamshire. Modules for the major M&E equipment, including gas-fired boilers, pump sets and multi- service risers, were also manufactured offsite at Crown House Technologies’ facility in Oldbury in the West Midlands. As Oxford University boasts 26 British prime ministers and at least 30 international leaders among its graduates, the school of government is well warranted. Many people, however, might have preferred the institution to bear the name of one of these, possibly Attlee or Peel – or Gandhi or Clinton, if the aim is to attract international students. But Oxford is by no means the only university to sell naming rights to its buildings: the Alliance Manchester Business School takes its name from benefactor Lord Alliance, while Imperial College has the Brevan Howard Centre for Financial Analysis, funded by a hedge fund set up by Alan Howard. And if you have millions of pounds to spare, Cambridge University’s website lists its central library as available as the “ultimate commemorative naming opportunity”. Blavatnik’s donation has allowed the university to commission one of the world’s best architects to design an extremely generous building. At £30m and 8,000 sq m, it’s also undoubtedly a lavish building for the school’s 120 students – as demonstrated by a quick comparison with the £70m, 16,200 sq m maths building that serves 900 students next door. But the budget has been put to good use, with Laing O’Rourke delivering a polished landmark that will certainly put the new school firmly on the international map. CM “We made the decision to treat all the concrete on the project as fair-faced; this reduced risk but increased cost” SteveHolland, LaingO’Rourke Opposite and below: The high-quality fair-faced concrete visible throughout the interior provided the contractor’s greatest technical challenge > LAINGO’ROURKE JOHNCAIRNS 30_34.CM.FEB16.Blavatnik.indd 34 18/01/2016 16:33