prisonstock

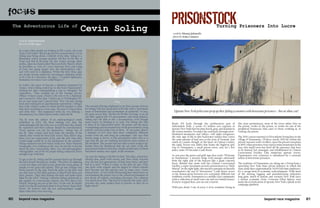

- 1. 60 beyond race magazine focus beyond race magazine 61 Route 374 leads through the northeastern part of Adirondack Park, a scenic 6.1 million acre expanse in upstate New York that becomes harsh, gray, and desolate in the winter months. For miles the road leads through snow- blanketed mountains and valleys—tall spiky evergreens, the only sign of life in this backwater tundra that covers the same amount of land area as the state of Vermont. Just south of Canada, though, in the heart of Clinton County, the rigid, frozen tree limbs that frame the highway give way to Dannemora, a small prison town, and, for a few miles, route 374 becomes Cook Street. As you pass the green and gold sign that reads “Welcome to Dannemora,” a massive beige wall emerges ominously from the right side of the horizon like a giant concrete beast. Behind that stone wall lies Clinton Correctional Facility, a super-maximum security prison known as “little Siberia”. In the right light, this massive panopticon literally overshadows the rest of “downtown.” Cook Street serves as the demarcation between two extremely different but symbiotic worlds. Dannemora is a middle class community with a collection of small-tract one and two family houses. If you’ve stopped here, you are not a tourist. With just about 3 out of every 4 of its residents living in this state penitentiary, most of the town either lives in the prison, works in the prison, or works for one of the peripheral businesses that cater to those working at, or visiting, the prison. The 2000 census reported 4,129 residents living here in the village of Dannemora. Of these, nearly 2900 lie within the prison’s massive walls. In effect, since the prison’s inception in 1845, when prisoners were used to mine mountains in the area, this small town has lived off the prisoners that have to be housed, fed, managed, and rehabilitated in Clinton Correctional Facility. Like numerous upstate towns, Dannemora’s very existence is subsidized by a constant influx of downstate prisoners. The residents of Dannemora are eking out a living from a sprawling New York State prison industry in which the state alone hires approximately 31,000 full time employees. It’s a savage form of economic redevelopment. With most of the mining, logging and manufacturing industries long gone, much of upstate and western New York faces a serious economic crisis. Governor Elliot Spitzer even made the revitalization of upstate New York a plank in his campaign platform. Upstate New York politicians prop up their failing economies with downstate prisoners—but at what cost? In a time when people are looking to fill a niche, the term “Jack of all trades” doesn’t get thrown around much. Cevin Soling may bring about a rebirth of the title. Soling is a filmmaker whose resume includes The War On The War on Drugs and Hole In The Head. He also writes strange short stories, plays in a band called The Love Kills Theory, which he describes as “sort of a cross between Devo and Gang of Four, but going deeper into the philosophical side,” and will soon be a diplomat. While the first three gigs are clearly artistic endeavors, becoming a diplomat seems to be a bit of a diversion. He jokes, “I wanted diplomatic immunity ever since I saw Lethal Weapon 2.” In reality, the quest to become a diplomat happened by chance, when Soling ended up on the State Department’s mailing list after contemplating a trip to Mongolia. He remembers, “They notified me of the Foreign Service Officer written exam, which is the test to be a diplomat, and I passed it. After that, I had to go to Washington DC for an oral exam and I passed that. Now I’m just sitting back and waiting for an appointment somewhere.” Soling’s lone wish, when it comes to where he’ll be headed, is, that they don’t send him to a war zone, “because I’ve been there and done that.” This happened when he was filming a documentary on a little known tribe called the Ik. The Ik were the subject of an anthropological study published in 1972; the final finding was that the anthropologist felt the tribe was so awful that they should be separated and their culture should be exterminated. “Every person was out for themselves,” Soling says of the Ik, “they would steal food from the mouths of the elderly, they would let their kids starve, they didn’t sing, there were no expressions of joy, and the only time they would laugh would be at the misfortune of one another.” Soling wanted to see how bad it really was. Since National Geographic was working in the area, he put the word out about his idea. Fortunately, there was one photographer/ videographer, out of the 40 people Soling contacted, brave enough to go with him. To get to the Ik, Soling and his partner had to go through the LRA (Lord’s Resistance Army): “The LRA was fighting a civil war there and they’re just about the worst group of people to ever grace this planet. They go into villages and shoot parents in the legs, hand the guns to the kids and say they have to kill their parents or they’ll kill them and their parents. Then they kidnap the kids and make them fight for the LRA.” During a mission Soling undertook to get supplies to a missionary outpost, the LRA shot at his vehicle, blasting out one of the tires. In the end, he finally made it to the Ik and found them to be in better shape than before. He believes that the last anthropologist caught them when they were starving. The concept of being a diplomat is one that screams of irony for Soling, who has spent most of his life with a “persistent sense of frustration and resentment of authority.” In fact, his most recent film, The War On The War On Drugs, is an all out blitz against the US government’s anti-drug policies. Soling says the film is not a documentary, even though many insist on labeling it as such. For Soling, the film is more of an educational satire. He points out the many wrongdoings and inconsistencies of the government’s drug policies and then pokes fun at them. At one point, there’s a mention of two stats that show completely different results from the anti-drug ad campaigns. One says that heroin usage is down, so the government takes this as a sign that the ads are working and throws more money at the situation. The second stat says that ecstasy usage is up. Rather than the likelihood that the ads don’t work, the government believes that they simply needed more of them and throw money, once again, at the situation. Up next for Soling is The War On Kids. This film, which he’s already shot, deals with society and “how badly screwed over the last few generations of kids have been, and how bad it is now.” When it comes to the plot, he says “This one deals with schools and the degree to which schools have become run like prisons and, in some cases, worse than prisons….It was really distressing how much nicer an environment the prison was to the school environment in just about all regards, including education…The cafeteria was much nicer also. The food is ironically the same. ARA provides the same quality food to prisons as they do to high school.” words by Adam Bernard photos by Kelly Segre The Adventurous Life of Cevin Soling Soling PRISONSTOCKTurning Prisoners Into Lucre words by Manny Jalonschi photos by Irma Cannavo

- 2. 62 beyond race magazine beyond race magazine 63 Although upstate New York produces less than a quarter of the state’s prison population, it holds over 90 percent of that population in its system. The $2.7 billion prison economy is often seen as a salve for the economic woes of these areas, and local politicians scramble to have their town be the next location of a prison expansion. A Georgia Pacific paper plant and Bombardier factory are the only other big employers in the region and they are nowhere near Dannemora. From a satellite photo, one would get a clearer impression of the real transaction that drives this city. There’s a big concrete pen. Those inside the pen represent the livelihoods of those outside the pen. The state is currently holding approximately 63,500 prisoners in its 69 state prisons. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, over 43,000 of those prisoners are residents of New York City and yet are incarcerated in an upstate prison, just about two out of every three prisoners. Conveniently enough, for funding and census purposes, prisoners are considered residents of the town they are imprisoned in. This alone is pretty good incentive to house a prison in an upstate region that needs as much government aid as possible. But besides the fact that this means that upstate districts get disproportionately high federal and state funds for residents that don’t actually live there, it also means that their upstate districts have a disproportionate amount of weight relative to the amount of residents actually living there. In effect, it takes less actual voters to fill up a legislative district. In upstate New York, this translates to 7 state senate districts that are more than 5 percent short of their required population, which, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, is a direct violation of a Supreme Court ruling on the subject. All 7 of those districts are represented by rural Republicans on the State Senate—all 7 of those Republicans advocate for stricter laws and lengthier sentences. Since 1984, of the 38 prisons that have been built to accommodate the inmate population, all 38 of them have been located in upstate New York. State legislators have one major reward in mind when they lobby for the building of a prison in their district: the revitalization of their economies. A prison offers the promise of hundreds of middle class-enabling prison jobs, most starting at over $30,000 a year, plus benefits. Some upstate politicians are better than others at getting a slice of the prison pie, and quite a few of them depend on the industry as an economic scaffold for their policies. State Senator Elizabeth O’C. Little (Rep.-Adirondacks) has over 5,000 corrections officers living in her district. There are 12 prisons and prison camps in her district, including Clinton Correctional Facility. State Senator Dale Volker, a former small-town policeman, has represented the heavily gerrymandered 59th Senate District with virtually unchallenged ease since 1975. FIve major prisons, Attica, Wyoming, Buffalo, Collins, and Wende, sit in his district generating thousands of jobs and padding up his already secure powerbase. He chairs the State Senate Committee on Codes from where he can protect his key moneymaker. Volker and fellow Republican State Senator Mike Nozzolio represent the two districts that house nearly one-quarter of the state’s prison population. Senator Nozzolio, whose district is home to four major prisons (Butler, Five Points, Auburn Correctional Facilities, and the Willard Drug Treatment Center) may very well be the master of getting prison industry money. With Five Points prison alone generating over $25 million in payroll annually, he has long fought for the best possible positions from which he can ensure a steady stream of “customers” for his district’s penitentiaries. After years of politicking his way up the state ranks, Nozziolio is Chairman of the Senate Crime Victims, Crime and Correction Committee (to which Senator Volker also belongs). Nozzolio also sits on the Finance committee and the Judiciary Committee (as does Volker). Through the Crime Victims, Crime and Corrections Committee, Nozzolio controls when and where new prisons will be built in the state. From the Finance Committee, he can now ensure the money is there for any prison development he may need in the future. From the Judiciary Committee, he controls which state judges do or do not get appointed, thus ensuring that stricter judges will eventually preside over New York State courtrooms (i.e. judges who will increase the inmate population). Nozzolio is an avid champion for “victims’ rights.” He has often used this as a catch phrase to push for laws requiring longer sentences. Nozzolio and Volker in fact have been among the staunchest opponents of a bill that would repeal the Rockefeller Drug Laws (which pack New York State prisons with non-violent drug offenders). But there is serious collateral damage in exchange for this Kafka-esque economic development strategy. While upstate communities benefit in jobs and additional traffic, downstate communities are hurt by the fracture of prisoners’ families. The New York State prison system, which ships three quarters of its prisoners from New York Citytoupstateandwesterntowns,essentiallyensuressuch a fracture. A drive from New York City up to Dannemora, for example, takes anywhere between 6 and 8 hours. From New York City, there are nearly $40 dollars of tolls along the way. In a compact car, it takes about $80 worth of gas to get you all the way north and back. Various “prison ride” bus companies have emerged to cater to families looking to visit members in distant upstate pens. In Brooklyn, they line up around 8 and 9pm, mostly mothers and girlfriends, in a shivering pecking order. Those who know the bus driver usually get the first pick of the seats. Then a blue Bic pen follows the names on the list and the bus fills towards the back. Sometimes there isn’t enough room, so those at the bottom of the list, or those who didn’t sign up, are left behind. The bus ride from Brooklyn, after dozens of winding stops to pick up other passengers, can take up to 14 hours, and cost anywhere from 40 to 60 dollars. The upside is you don’t pay for gas and tolls. The downside is up to 30 hours on the road. For New York City families, these trips are a Herculean effort to reunite with their loved ones. But much more goes on then just conversations. During these family visits, ties are maintained, built and strengthened with members of the family as well as the community. These ties have been shown in numerous studies to be key in successful reentry into society. When an inmate leaves prison, he or she relies heavily on these connections to find housing and employment (the other two key elements in successful reentry). Without these connections, prisoners face a very challenging road back alone. Jerry, now in his late 50’s, with a wrinkled bulldog face, remembers his 24 years in Comstock (another upstate prison) with loneliness and dread. Serving time for an assault in the Bronx in the late ’70s, Jerry always thought he’d get out before his term was up. “They gave me all this extra time—they were ‘getting tough’ on crime back then,” says Jerry wryly over a cup of coffee at his ex-inmate support group. His mother, the only family he’s ever had, never owned a car and could never find a ride to visit him while he was imprisoned. They wrote back and forth, though, and when the letters suddenly stopped, Jerry lost his only contact with the outside world. It would take him nearly a year to find out that his elderly mother had suffered a heart attack and died alone in a Coney Island hospital. “When you come out, that’s when you remember how much time has passed you by, how much you don’t know and how much you need people.” Jerry had no contacts in the outside world. Without a job, family, or an apartment, Jerry had nothing to start over with. “They’re not gonna hire you with a criminal record, everyone knows that.

- 3. 64 beyond race magazine beyond race magazine 65 They’re not gonna hire you without an address, everyone knows that. So you tell me, how the fuck am I supposed to get my life together?” The truth is that the recidivism rate in the United States is abnormally high. Two in three released prisoners are re-incarcerated within three years. Drug offenders are not rehabilitated, merely punished. This ensures they will violate again. Additionally, there is little to no effort made to create bridges between convicts and the communities from which they come; ties that would ensure a lower crime-rate for the state and a return to normalcy for the former prisoner. The state spends little if any money on programs that seek to train prisoners in a relevant work skills, thus ensuring they will be unemployed when they exit. Jerry for example, took two and a half years of small motor repair, and says, “I don’t see any lawnmowers in my section of the Bronx.” Despite the fact that any of these prison alternatives cost a small fraction of what it cost to house and feed a prisoner, upstate politicians have fought repeatedly for tougher laws instead. Tougher laws and less prisoner support equals more prisoners. More prisoners equals more prison money. From the profit end, it’s a pretty simple equation. The result downstate is a criminality cycle, where inmates (especially inmate parents) upon release are more likely to re-offend because of a lack of any connection to family and community; and their family and community is more likely to become criminalized due to separation from a member of that family or community. More simply put, upstate politicians push for stricter laws and longer sentences because it maintains a large enough prison population to keep up their local prison economies. They have everything to gain, both in funds and legislative weight, and very little to lose (there are no mansions lining Cook Street in Dannemora anyway, per se). And there is little hope that this will ever change. In 2007, New York Governor Elliot Spitzer announced that, since the prison population has been declining, some prisons will eventually have to be closed. State Senators Volker, O’C. Little and Nozzolio all immediately and uniformly opposed the move. If they hadn’t, they’d probably lose their jobs. The New York State Correctional Officers and Police Benevolent Association has spent nearly $2 million in recent years on campaigns to ensure tougher laws with longer sentences. And so it continues, a sick game of exploitation where state politicians actively pursue an increase in the prison system. It’s a Rockwell reality on methamphetamines. Middle-class towns surviving mostly on the subjugation of lower-class, downstate urban towns. Although upstate New York produces less than a quarter of the state’s prison population, it holds over 90 percent of that population in its system. And so for decades now, and probably for decades still, families have been built around the suppression and processing of fellow humans. After all, here on Cook Street, it’s quite obvious. Little but snow is produced in Dannemora. Whatever youth there is quickly escapes to nearby Plattsburgh in search of life. There is nothing here…just a big brick jail and a town of jailers. “They’re not gonna hire you with a criminal record, everyone knows that. They’re not gonna hire you without an address, everyone knows that. So you tell me, how the fuck am I supposed to get my life together?”