Spotlight_Uganda_0215

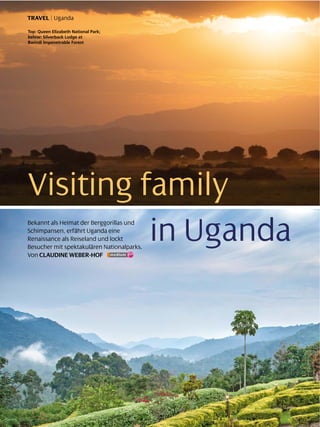

- 1. Spotlight 2|1514 TRAVEL | Uganda Visiting family in UgandaBekannt als Heimat der Berggorillas und Schimpansen, erfährt Uganda eine Renaissance als Reiseland und lockt Besucher mit spektakulären Nationalparks. Von CLAUDINE WEBER-HOF Top: Queen Elizabeth National Park; below: Silverback Lodge at Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

- 2. 2|15 Spotlight 15 Topi antelope; a fish eagle; a baby gorilla in Bwindi

- 3. Spotlight 2|1516 TRAVEL | Uganda The chimps of Kibale It’s 8 a.m. in the self-proclaimed primate capital of the world. Ranger Jeffrey Ta- zenya counts the great apes before him: five Canadians, two Germans, three Ital- ians, one South African, a Brit and an American. We completely fill the small visitor centre in Kibale National Park in western Uganda. Our goal is to track other great apes — some of our closest cousins, the chimpanzees. People visit Kibale to see its large pop- ulation of chimps: more than 1,400 of them live here. Rangers of the Uganda Wildlife Authority practically guarantee that we will see the animals, but as we start to walk through the tropical forest, I’m sceptical. Uganda is where the savannah of East Africa meets the jungle at Africa’s heart. Stepping over ferns and fallen trees, it’s clear we’ve left the open grassland; above us, tall palms block the sky. With all this vegetation, how can anyone see the chimps? Ranger Tazenya leads us further into the jun- gle, stopping to listen for chimp chatter. Of the 11 chimpanzee communities in Kibale, he says, five are habituated — that is, five of the groups are somewhat used to seeing people. Roughly 120 chimps get regular visits from tourists, while another 200 of them are being studied by Kampala’s Makerere University. It takes a full five years to habituate a community, which can split into smaller groups of five, ten or twenty chimps at any time. “Females can cross into any group, and they will be welcomed,” Tazenya explains, sot- to voce. “But a male cannot cross. If he makes that mistake, he will be killed.” Even females with male young must be careful; adult males see the babies as a threat. “But within the same community,” Tazenya says, “the chim- panzees are peaceful.” The ranger’s radio comes to life, and we hurry deeper into the jungle. I trip over plants and struggle through mud. Tazenya gives me a hand, pulling me across a stream. Just then, chimp chatter echoes through the air. We rush towards the sound. Minutes later, we meet the Cana- dian group. Above them, high up in a tree, is a large chimp eating leaves. Near- by, small monkeys jump about, making the forest canopy sway. The big chimp’s name is Totti — after Francesco Totti, the Italian footballer. Tazen- ya explains that males typically live to be- come up to 55 years of age, females to 45. Males are fully mature at six, while females mature at 13, which is when they can con- ceive. Over her lifetime, a female chimp will have between four and six offspring. canopy [(kÄnEpi] Baumkronendach chatter [(tSÄtE] Geplapper, Geschnatter chimp [tSImp] ifml. Schimpanse conceive [kEn(si:v] empfangen fern [f§:n] Farn great ape [)greIt (eIp] Menschenaffe habituated [hE(bItSueItId] gewöhnt mature [mE(tSUE] erwachsen, ausgewachsen offspring [(QfsprIN] Junge, Nachwuchs self-proclaimed [)self prEU(kleImd] selbst ernannt sotto voce [)sQtEU (vEUtSi] mit gedämpftem Ton sway [sweI] schwanken, hin- und herbewegen Ready for adventure: a ranger with visitors to Kibale National Park Follow me: park ranger Jeffrey Tazenya The chimp named Totti: the next alpha male? AlleFotos:DavidJohnWeber

- 4. 2|15 Spotlight 17 The focus of any chimp group, however, is the alpha male. He has to be able to command his chimps and attack outsiders to expand his terri- tory. But his main function is to keep the peace. Once he’s too old for the job, he can remain with his orig- inal clan, as long as he respects the new boss. Tazenya says that Totti is about 26 years old and may become the next alpha male. All the while, Totti has been lis- tening to us and considering his next move. He decides to climb down the tree. “Che bello, bellissimo,” says one of the Italians in our group. Totti’s face is gentle, his expression open and relaxed. He picks leaves from a bush, then walks away on all fours. We follow, watching him eat. Every move he makes is photographed, and discussed in multiple languages. After 40 minutes, Totti disap- pears up another tree. “We’ve had quite a bit of time with him,” our ranger says, looking pleased. “Let’s call it a day.” Lions under pressure Kibale National Park is connected by a wildlife corridor to Queen Eliza- beth National Park, our next desti- nation. As we drive there, I photo- graph the corn and matoke bananas growing near wood-shack villages. “People here are poor, but they have food,” guide Eric Ndorere explains. It’s late afternoon when we reach the well-known park. From the jeep, I see the golden savannah and areas of green that are island-like, each with a single euphorbia tree. In the distance, the wall of the Albertine Rift, the great, biodiverse valley in which we find ourselves, rises to meet the sky. Ndorere identifies some of the birds: red-billed fire finch and African wattled lapwing. Long before he became Britain’s prime minister, Winston Churchill visited Uganda in his role as the under-secretary of state for the colonies. Of his travels there in 1907, he wrote: “The kingdom of Uganda is a fairy-tale … a wonderful new world. The scenery is different, the vegetation is different, the climate is different, and, most of all, the people are different from anything elsewhere to be seen in the whole range of Africa ... I say: ‘Concentrate on Uganda.’ For magnificence, for variety of form and colour, for profusion of brilliant life — bird, insect, reptile, beast — for vast scale, Uganda is truly the pearl of Africa.” This pearl, a British protectorate from 1894 to 1962, is now being rediscovered. Travellers go there for the same reason that researchers Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey fell in love with neighbouring Tanzania and Rwanda respectively: the primates. Along with its many chimpan- zees and monkeys, Uganda’s jungle contains half the world’s remaining population of rare mountain gorillas. There’s more, though: the country is located in the African Great Lakes region of the East African Rift. Lake Victoria, close to the capital of Kampala, is the world’s largest tropical lake and one of the sources of the Nile. Uganda has an average altitude of 1,100 metres above sea level, giving the country a comfortable climate, especially during the dry seasons (June to August/September and December to February). English is taught in the schools and is one of the official languages of Uganda. WHY VISIT UGANDA? King of the savannah: an endangered lion rests in the grass Kob antelope in Queen Elizabeth National Park altitude [(ÄltItju:d] Höhe fairy tale [(feEri teI&l] Märchen jungle [(dZVNg&l] Dschungel, Urwald let’s call it a day [lets )kO:l It E (deI] machen wir Schluss für heute magnificence [mÄg(nIfIsEns] Pracht, Herrlichkeit pearl [p§:l] Perle profusion [prE(fju:Z&n] Überfluss, Überfülle red-billed fire finch [)red bIld (faIE fIntS] Roter Amarant respectively [ri(spektIvli] jeweils source [sO:s] Quelle, Quellsee wattled lapwing [)wQt&ld (lÄpwIN] Lappenkiebitz wood-shack [(wUd SÄk] Bretterbuden-

- 5. Spotlight 2|1518 TRAVEL | Uganda A kilometre on, Ugandan kob are doing battle. A lone female antelope sits with what looks like a smile on her face, watching the men lock horns. Ndorere explains that female kob choose the males with which they have young — not, as with many other antelope, the other way round. Driving on, we see lions waiting for dark and the hunt. Two of them roll in the grass as the sun makes a rose-coloured exit behind the tall Rwenzori Mountains. Morning brings out the beauty of Mweya Safari Lodge, where we’ve stayed the night. High-ceilinged and grand, its lobby evokes British colonials in starched khaki and pith helmets. The hotel sits on a peninsula above the Kazinga Channel, which connects Lake George to Lake Edward. Lake Edward, the smallest of the African Great Lakes, was named in 1888 after Britain’s Prince Albert Edward by Henry Morton Stanley, the Welsh journalist and explorer who had found fame in Tanzania several years before: on 10 November 1871, Stanley is said to have greeted a long-lost Scottish missionary with the well- known words, “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” At the lodge, I shake hands with Dr Ludwig Siefert and James Kalyewa of the Uganda Carnivore Program. The researchers are working with California’s Oakland Zoo to develop an education and community programme in the park. Their goal is to decrease the pressure that the locals are putting on the wildlife. Siefert explains that there are 30,000 people living in Queen Elizabeth and another 70,000 just outside it. Many of them keep live- stock — easy meals for lions, leopards and hyenas. When livestock are killed, people react by poisoning the preda- tors. But to do so is to eliminate the top attraction in Uganda’s most popular national park. As we drive into the park, Siefert tells me more. With so many sources of stress — including conflicts with lo- cals and tourists driving too close to the animals — al- most no female lions are being born. What’s more, some of the animals leave, crossing from Queen Elizabeth into Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Kalyewa extends an antenna out of the jeep. He gets a signal, then takes us off the dirt track into the bush. Within minutes, we’re witnessing a waterbuck kill: a female lion, with two of her children, is feeding on the large antelope. Siefert smiles. “This is one of our older females,” he says. “She’s very protective of her cubs.” Next, Kalyewa finds a coalition of three young males. “See that one there,” Siefert says of a lion with a dark mane. “He was once on the cover of National Geographic.” When Queen Elizabeth National Park was created in the 1950s, it had huge numbers of large mammals. Dur- ing the Uganda-Tanzania War of 1978–79, Siefert says, they were decimated by rebel groups and people desperate to eat. Others say that the biggest losses occurred before then, during the rule of dictator Idi Amin (1971–79). To- day, Queen Elizabeth is home to 95 mammal species and 500 species of bird. Populations of hippopotamus and elephant are making a strong comeback. cub [kVb] Junges evoke [i(vEUk] heraufbeschwören high-ceilinged [)haI (si:lINd] mit hoher Zimmerdecke hyena [haI(i:nE] Hyäne kob [kQb] Grasantilope leopard [(lepEd] Leopard livestock [(laIvstQk] Vieh lobby [(lQbi] Foyer, Eingangshalle lock horns [lQk (hO:nz] seine Kräfte mit jmdm. messen lodge [lQdZ] Hütte; hier: Hotel mammal [(mÄm&l] Säugetier mane [meIn] Mähne peninsula [pE(nInsjUlE] Halbinsel pith helmet [ (pIT helmIt] Tropenhelm predator [(predEtE] Raubtier presume [pri(zju:m] vermuten, annehmen starched [stA:tSt] gestärkt waterbuck [(wO:tEbVk] Wasserbock witness [(wItnEs] Zeuge sein, erleben James Kalyewa of the Uganda Carnivore Program

- 6. 2|15 Spotlight 19 To keep all of the animals from harm, Siefert says, lo- cal people need to see the wildlife not as food, but as the attraction bringing in visitors who will buy their artworks and take “cultural tours” of the villages. Only then will the illegal killing stop. “They feel left out of the tourism market,” Siefert explains. “But once you have the com- munity on your side, you have a win-win.” Birds on the Kazinga Channel Four o’clock may be when some people start to long for afternoon tea, but for us, the hour means boating on the Kazinga Channel. The waterway is a paradise for birds — and birders. Our boat crosses the channel, and a colo- ny of pied kingfishers comes into view. Fish eagles hunt, and spoonbills fish, while nearby, several Nile crocodiles sleep in the sun. Monitor lizards watch from trees as hip- pos bathe in the mud. Elephants, a column of them, march off into the distance, just having finished their af- ternoon ablutions. The day is still hot, and an “old boys’ club” of Cape buffalo — senior males long since driven from the herd — lounge on the shore so that oxpeckers can eat ticks from their faces. Ibis, grey with a green shine on their wings, surprise us with their loud cries. An egret lifts off, its white feathers a brilliant contrast to the deep green of the trees. Most of these birds live in the Maramagambo Forest, a chimpanzee-rich area of Queen Elizabeth ablution [E(blu:S&n] Waschung bathe [beID] baden birder [(b§:dE] N. Am. ifml. Vogelbeobachter(in) egret [(i:grEt] Reiher fish eagle [(fIS )i:g&l] Fischadler herd [h§:d] Herde kingfisher [(kIN)fISE] Eisvogel monitor lizard [(mQnItE )lIzEd] Waran oxpecker [(Qks)pekE] Madenhacker pied [paId] bunt, gescheckt shore [SO:] Ufer, Strand spoonbill [(spu:nbIl] Löffler tick [tIk] Zecke An egret takes flight; a Kazinga Channel fisherman Kazinga Channel: a paradise for birds; left, Cape buffalo

- 7. Spotlight 2|1520 TRAVEL | Uganda National Park. But exotic visitors fly in, too: flamingos arrive in the park’s salt lakes every October, an event that draws international attention. Several big Vs appear in the sky. Cormorants are flying in. As they pass, our boat reaches the channel fishing community. The village gets support from Mweya Lodge — money that has helped to rebuild the school. The lo- cals also sell 250 tilapia to the hotel kitchen each week. We watch as men prepare their nets and paddle their ca- noes to Lake Edward, where they will fish for most of the night. Following them, we reach the channel’s end. Lake Edward opens before us like the sea. Friday with gorillas In the Ishasha Sector of Queen Elizabeth National Park, travellers use the word “Congo” to mean a wilderness they might never see. Other than a few nature reserves that are open to tourists, its political instability makes the DRC a tough place to visit. On the Ugandan side of the border, though, the greatest danger may be the tree-climbing lions. Their legs hang down from the big fig trees where they are asleep at midday. We stop the jeep to take a look. Our guide explains that it’s cool up in the trees, and from there, the lions can watch for Topi antelope. Later in the day, we drive past guide Eric Ndorere’s home town of Kihihi. Workers queue outside tea factories right next to the bright green tea plantations that blanket the land. The farming stops where Bwindi Impenetrable Forest begins. Mountain gorillas are its main attraction; more than 400 of them live here. I have a perfect view of their habitat when we arrive at Silverback Lodge. Rising above the hotel gardens, the jungle hills seem inviting. With tall mahogany trees and a thick carpet of plants, they exude a feeling of safety — of a home in the wild. It’s a place utterly familiar to Medad Tumugabiiewe, or Medi, as he asks us to call him. The ranger has been at Bwindi since part of the forest opened as a national park in 1991. The gorilla trek he’ll be leading can take up to eight hours. The paths, made by the Batwa pygmies who once lived in the jungle, are steep. We will be tracking the 17-member Rushegura family of gorillas. Its dominant silverback — so called because of the grey fur seen on senior males — has recently died. Now a new leader is in charge. Certain gorilla families have been habituated to hu- mans: about half the gorillas in this park. American re- searcher Dian Fossey, who worked with the mountain gorillas of Rwanda, described them as gentle. “After more than 2,000 hours of direct observation,” she wrote in Na- tional Geographic in 1970, she’d seen “less than five min- utes of what might be called ‘aggressive’ behaviour. And even this really amounted to protective action or bluff.” Medi’s advice to us is to keep a distance of seven metres from the gorillas when we see them. in charge: be ~ [In (tSA:dZ] das Sagen haben exude [Ig(zju:d] ausstrahlen, verströmen fig tree [(fIg tri:] Feigenbaum pygmy [(pIgmi] Pygmäe, Pygmäin tilapia [tI(lÄpiE] Buntbarsch utterly [(VtEli] absolut, gänzlich The new silverback: boss of the Rushegura gorilla family Taking a break: a lion in the Ishasha Sector

- 8. 2|15 Spotlight 21 We hike uphill through a tunnel of banana trees. Each of us has a walking stick, which helps immensely with rocky areas, and many of us have hired local porters to carry our packs. After an hour, we take a break. When the trek continues, Medi shows us the trails used by gorillas to go deeper into the bush. “Gorillas make nests on the ground,” he says, “and an individual makes a nest every night.” After two hours, we’ve hiked up to 1,700 metres, the top of the mountain. The trackers, who had gone out an hour ahead of us to locate the gorillas, rest at the side of the path. We pass by them, expressing our thanks, and follow Medi to an area where we can hear the gorillas moving in the trees. Soon they appear: young males and adult females with babies, all looking for leaves to eat. None of them seem at all concerned about our presence. Being this close to gorillas creates the strong need to anthropomorphize: they seem so very human. As I watch, a mother gathers her baby to her chest, allowing her tiny boy to nurse. Two teenagers sit together and groom each other. It looks as though they are waiting for someone else to appear. Just then, the big silverback walks out of the bush. The junior members of the group watch him to see what to do next. Are we humans really so different? After nearly an hour, the gorillas have had enough of us and disappear into the jungle. Fossey wrote that we “human trespassers” were pushing too far into the limited areas where mountain gorillas can still live in the wild. Turning to leave, I wonder if careful tourism like this will create the balance necessary to keep local communities happy and the population of gorillas growing. Who knows? It may just work. IF YOU GO Getting there Fly with Ethiopian Airlines to Entebbe International Airport (EBB) in Uganda via Ethiopia’s Bole International Airport (ADD) in Addis Ababa. For more information, see www.ethiopianairlines.com Purchase your visa for US $50 upon arrival in Entebbe. Be sure to have exactly the right cash on hand. Getting around Premier Safaris specializes in tours of East Africa and has a top-class programme in Uganda. Services include assistance with visas upon arrival, connecting flights, bookings at lodges, gorilla-trekking permits, guides who specialize in photography (such as well-known photographer Albie Venter) and much more. As part of the well-established Marasa Africa group, its hotels include beautiful places in national parks, such as Mweya Safari Lodge in Queen Elizabeth National Park and Silverback Lodge at Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. See www.premiersafaris.com Money At many hotels, you can pay in Ugandan shillings, US dollars or sometimes in euros. Visa is often the only credit card accepted, but do not rely on credit cards alone. Trip preparation See a doctor who specializes in travel medicine before visiting this tropical country. A vaccination for yellow fever is required to enter Uganda and is available only at certain locations (Gelbfieberimpfstelle; Tropeninstitut). Other vaccinations may be necessary, too, as well as malaria tablets. Ask about strong insect repellents to guard against mosquito bites, as well as protective clothing for trekking. (The UK company Craghoppers makes a special line of anti- mosquito shirts, for example.) More information See www.visituganda.com anthropomorphize [)ÄnTrEpEU(mO:faIz] menschliche Eigenschaften zus- chreiben groom [gru:m] sich pflegen, sich putzen hike [haIk] wandern porter [(pO:tE] Träger(in) tracker [(trÄkE] Fährtenleser(in) trespasser [(trespEsE] Unbefugte(r), Eindringling vaccination [)vÄksI(neIS&n] Impfung Views of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest from the Silverback Lodge