A Wasted Decade - Syria

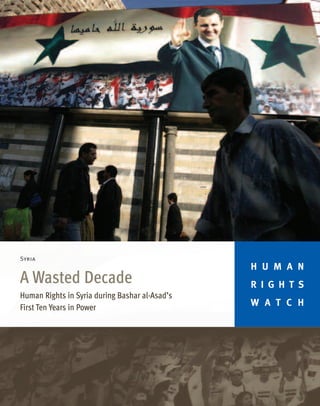

- 1. Syria H U M A N A Wasted Decade R I G H T S Human Rights in Syria during Bashar al-Asad’s First Ten Years in Power W A T C H

- 2. A Wasted Decade Human Rights in Syria during Bashar al-Asad’s First Ten Years in Power

- 3. Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-663-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 hrwnyc@hrw.org Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 berlin@hrw.org Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 hrwbe@hrw.org 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 hrwgva@hrw.org 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 hrwuk@hrw.org 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 paris@hrw.org 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 hrwdc@hrw.org Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org

- 4. July 2010 1-56432-663-2 A Wasted Decade Human Rights in Syria during Bashar al-Asad’s First Ten Years in Power Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 I. Repression of Political and Human Rights Activism .......................................................... 5 II. Restrictions on Freedom of Expression .......................................................................... 11 III. Torture, Ill-Treatment, and Enforced Disappearances ................................................... 18 IV. Repression of Kurds .................................................................................................... 23 V. Legacy of Enforced Disappearances .............................................................................. 26 VI. Annex: List of Political and Human Rights Activists Detained during Bashar al-Asad’s First Decade in Power ....................................................................................................... 29

- 5. Executive Summary After Bashar al-Asad succeeded his father as president in July 2000, many people in Syria hoped that the human rights situation would improve. In his first inaugural speech on July 17, al-Asad spoke of the need for “creative thinking,” “the desperate need for constructive criticism,” “transparency,” and “democracy.”1 A human rights lawyer summed up his initial feelings on the succession, reflecting the mood and aspirations of many others in the country: “Bashar’s inaugural speech provided a space for hope following the totalitarian years of President [Hafez] Asad. It was as if a nightmare was removed.”2 Ten years later, these initial hopes remain unfulfilled, and al-Asad’s words have not translated into any kind of government action to promote criticism, transparency, or democracy. This report reviews Syria’s human rights situation in five key areas and proposes concrete recommendations to the Syrian President that are essential to improving Syria’s human rights record. The Damascus Spring that followed al-Asad’s ascent to power, during which a number of informal groups began meeting in private homes to discuss political reform, was a short- lived experiment; its highpoint was the shutting down of Mazzeh prison in November 2000 and the release of hundreds of political prisoners shortly thereafter. It came to an abrupt end in August 2001; Syria’s prisons are filled again with political prisoners, journalists, and human rights activists (Annex 1 lists 92 political and human rights activists detained since al-Asad’s ascent to power). Syria’s opaque decision-making process and the lack of public information on policy debates within the regime make it very difficult to know the real reasons that drove Bashar al-Asad to loosen some of the existing restrictions early on, only to clamp down a few months later and to maintain a tight grip ever since. Was al-Asad a true reformer who did not have the capacity early in his reign to take on an entrenched “old guard” that refused any political opening? If so, why has he not implemented these reforms in the ensuing years after he had consolidated his power base and named his own people to key positions? Or was al-Asad’s talk of reform a mere opportunistic act to gain popularity and legitimacy that he never intended to translate into real changes? 1 Translation of President Bashar al-Asad's July 17, 2001 inauguration speech provided by the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA), via http://www.al-bab.com/arab/countries/syria/bashar00a.htm. 2 Human Rights Watch interview with Syrian human rights activist (name withheld), Damascus, November 14, 2006. 1 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 6. There is not enough publicly available information to answer these questions definitively. However, it is clear that after a decade in power, Bashar al-Asad has not taken the steps necessary to truly improve his country’s human rights record. He has focused his efforts on opening up the economy without broadening public freedoms or establishing public institutions that are accountable for their actions. So while visitors to Damascus are likely to stay in smart boutique hotels and dine in shiny new restaurants, ordinary Syrians continue to risk jail merely for criticizing their president, starting a blog, or protesting government policies. The state of emergency, enacted in 1963, remains in place, and the government continues to rule by emergency powers. Syria’s security agencies, the feared mukhabarat, continue to detain people without arrest warrants, frequently refuse to disclose their whereabouts for weeks and sometimes months, and regularly engage in torture. Special courts set up under Syria’s emergency laws, such as the Supreme State Security Court (SSSC), sentence people following unfair trials. Syria is still a de facto single-party state with only the Ba`ath Party holding effective power. Bashar al-Asad has permitted Syrians to access the internet but his security services detain bloggers and censor popular websites such as Facebook, YouTube, and Blogger (Google’s blogging engine). On September 22, 2001, one year after al-Asad assumed power, the Syrian government adopted a new Press Law (Decree No. 50/2001), which provided the government with sweeping controls over newspapers, magazines, and other periodicals, as well as virtually anything else printed in Syria, from books to pamphlets and posters. Despite statements by First Lady Asma al-Asad in January 2010 that the government “wanted to open more space for civil society to work,” Syria’s security services continue to deny registration requests for independent non-governmental organizations and none of Syria’s human rights groups are licensed.3 The Kurdish minority, estimated to be 10 percent of the population, is denied basic group rights, including the right to learn Kurdish in schools or celebrate Kurdish festivals, such as Nowruz (Kurdish New Year). Official repression of Kurds increased further after Syrian Kurds held large-scale demonstrations, some violent, throughout northern Syria in March 2004 in order to voice long-simmering grievances. Since then, security forces have dispersed Kurdish political and cultural gatherings, sometimes with lethal force, and have detained a 3 Cited in Rami Khouri, “Signals of Change from Syria,” Agence Global, January 27, 2010, http://www.agenceglobal.com/article.asp?id=2244 (accessed June 10, 2010). A Wasted Decade 2

- 7. number of leading Kurdish political activists, who they have referred to military courts or the SSSC for prosecution under charges of “inciting strife,” or “weakening national sentiment.” Despite repeated promises by al-Asad, an estimated 300,000 stateless Kurds are still waiting for the Syrian government to solve their predicament by granting them citizenship. Most of these had their Syrian citizenship stripped by the Syrian government after an exceptional census in 1962 or are their descendants. Promises by al-Asad for new laws that would broaden political and civil society participation have not materialized. In March 2005 he promised while speaking to Spanish journalists that “the coming period will be one of freedom for political parties in Syria.”4 In June 2005 the Ba`ath Party Congress recommended the establishment of a new political party law that would allow the creation of new non-ethnic and non-religious political parties.5 To date, no new draft law has been officially introduced. Repression in Syria today may be less severe than during Syria’s darks years in the early 1980s, when security forces carried out large-scale disappearances and extrajudicial killings. But that is hardly an achievement or measure of improvement given the different circumstances. As a prominent dissident told Human Rights Watch recently, “In the 1980s, we went to jail without trial. Now, we get a trial, but we still go to jail.”6 In public interviews and speeches, al-Asad has justified the lack of political reforms by either arguing that his priority is economic reform, or by stating that regional circumstances have interfered with his reform agenda. In his second inaugural speech in July 2007, following an endorsement for a second term with 97.6 percent of the vote, al-Asad noted that: Numerous circumstances hindered some of the political developments which we wanted to achieve. Our supreme objective, amidst the chaos certain parties have been exporting to our region—and which surrounds us now— was to preserve the safety and security of our citizens and maintain the stability our people enjoys.7 4 Sami Moubayed, “Syria's Ba`athists Loosen the Reins,” Asia Times, April 26, 2005, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/GD26Ak04.html (accessed May 12, 2010). 5 Rhonda Roumani,“In Syria, Democrats Chomp at Bit,” Christian Science Monitor, September 23, 2005, http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0923/p06s03-wome.html (accessed May 12, 2010). 6 Human Rights Watch interview with Syrian political activist, Beirut, April 5, 2010. 7 Bashar al-Asad’s Second Inaugural Address on July 18, 2007, available at http://www.mideastweb.org/bashar_assad_inauguration_2007.htm (accessed on June 10, 2010). 3 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 8. While there is no doubt that Syria has faced numerous foreign policy challenges in the last decade, from the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 to Syria’s forced withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005 and its subsequent isolation by Western powers, these do not explain, let alone justify, the Syrian government’s repressive behavior toward its own citizens. A review of Syria’s record shows a consistent policy of repressing dissent regardless of international or regional developments. Al-Asad’s crackdown on dissidents began in August 2001, before the United States invaded Iraq, and continued throughout the decade, irrespective of the state of Syria’s relations with the international community. Syria’s emergence from its Western-imposed isolation since 2007 has not improved the situation for Syria’s political and human rights activists. In March 2007, the European Union reopened its dialogue with Damascus, after it had suspended talks on an EU association agreement in 2005 following the murder of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri. The US followed suit, with House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi meeting al-Asad in Damascus in April 2007, followed by a visit to Syria in May 2007 by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Yet, in May 2007, Syrian courts sentenced leading dissident Kamal Labwani and prominent political writer Michel Kilo to long jail terms for their peaceful activities, only weeks after jailing human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni. More recently, Europe’s, and particularly France’s, extensive engagement with Syria following al-Asad’s visit to Paris in July 2008 has not eased Syria’s repression of human rights activism. On July 28, 2009, the government detained Muhanad al-Hasani, a human rights lawyer and the foremost monitor of the State Security Court. Three months later, on October 14, 2009, it detained Haytham al-Maleh, 78, a human rights lawyer who criticized the regime’s policies on an opposition TV station. Writing ten years ago in June 2000, Riad al-Turk, a prominent Syrian opposition leader and the former secretary general of the Syrian Communist Party (Political Bureau), asked in an article whether Syria will remain a “Kingdom of Silence”—a country where criticism of government policies is banned. His question still resonates today. Without reform in the five areas outlined in this report, al-Asad’s legacy will merely extend that of his father: government by repression. A Wasted Decade 4

- 9. I. Repression of Political and Human Rights Activism In the early months of his rule, Bashar al-Asad emphasized the principle of openness. Sensing a possible opportunity, many political and human rights activists began to raise their voices to demand the introduction of greater freedoms and political reforms in Syria. A number of informal groups began meeting in private homes to discuss human rights and reform efforts. The authorities allowed these forums to take place, leading to a period of relative openness often referred to as the “Damascus Spring.” By early 2001, 21 such informal groups functioned across Syria. 8 However, al-Asad’s brief promotion of tolerance came to an abrupt end. On January 29, 2001, Syrian Information Minister Adnan `Omran declared that civil society is an “American term” that had recently been given “additional meanings” by “groups that seek to become (political) parties.”9 A month later, al-Asad repeated the warnings to the civil society movement: When the consequences of an action affect the stability of the homeland, there are two possibilities: either the perpetrator is a foreign agent acting on behalf of an outside power, or else he is a simple person acting unintentionally. But in both cases a service is being done to the country’s enemies, and consequently both are dealt with in a similar fashion, irrespective of their intentions or motives.10 The crackdown began in August 2001. On August 9 the security services detained Ma’mun al-Homsi, a deputy in the People’s Assembly known for his criticism of the regime. Subsequent arrests of prominent political and rights activists soon followed, and within a month, Syrian authorities had arrested 10 opposition leaders, including two members of parliament, and cracked down on civil society advocacy groups. The two lawmakers, al- Homsi and Seif, were convicted of “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means” and “inciting racial and sectarian strife,” and sentenced by the Damascus Criminal Court to five years in jail. The other eight activists, Riad al-Turk, `Aref Dalilah, Walid al-Bunni, Kamal 8 To read more about the mood in Syria at the time of Bashar al-Asad's accession to power, see Alan George, Syria: Neither Bread nor Freedom (London: Zed Books, 2003), pp. 30-33; Eyal Zisser, Commanding Syria: Bashar al-Asad and the First Years in Power (London: I.B. Taurus, 2007), pp. 77-81. 9 “The Emergency Law is Present but Frozen,” Al-Dustour (Amman, Jordan), January 30, 2001. 10 “Interview with Bashar al-Asad,” Asharq al-Awsat, February 8, 2001, http://www.al- bab.com/arab/countries/syria/bashar0102b.htm (accessed June 10, 2010). 5 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 10. al-Labwani, Habib Salih, Hasan Sa`dun, Habib `Isa, and Fawwaz Tello, were referred to the Supreme State Security Court, which issued prison sentences of between two to ten years.11 There is virtually no information from Syria to explain why al-Asad initially promised an expansion of freedom only to subsequently reverse his policy. Al-Asad may have feared that what he had planned as a controlled and superficial opening would gain momentum and translate into a wider challenge to his regime. Some analysts argued that by demanding free elections, opposition members and civil society activists had directly challenged a yet- untested al-Asad which forced him to clamp down. 12 Other analysts focused on the role of the “old guard” that surrounded al-Asad, who never looked kindly on any political opening that could challenge their authority. In the words of Eyal Zisser, author of multiple books on Syria, “the old guard forced him [al-Asad] to reverse gears” and pushed him into “leading a counterattack against the supporters of reform.”13 Regardless of the underlying reasons, the crackdown on the Damascus Spring in the absence of any real threat to the regime seems to indicate that al-Asad was not truly committed to political reforms. Since then, the Syrian authorities have regularly detained political and human rights activists. Human Rights Watch has documented the arrest of at least 92 political and human rights activists since al-Asad came to power (See Annex 1). However, the actual number is likely much higher, given that it is hard to obtain information about the detention of less prominent political activists, especially Kurds and Islamists. In detaining and prosecuting activists, Syrian authorities rely on the emergency law, which gives the security services broad powers of arrest, as well as broadly worded “security” provisions in Syria’s Penal Code, such as “issuing calls that weaken national sentiment or awaken racial or sectarian tensions while Syria is at war or is expecting a war” (Article 285 of Syrian Penal Code), “spreading false or exaggerated information that weakens national sentiment while Syria is at war or is expecting a war” (Article 286 of Syrian Penal Code), or undertaking “acts, writings or speech that incite sectarian, racial, or religious strife” (Article 307 of Syrian Penal Code). 11 For more information regarding the crackdown on the Damascus Spring movement, see Amnesty International, “Syria Smothering Freedom of Expression: the Detention of Peaceful Critics,” AI Index: MDE 24/007/2002, June 6, 2002, http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGMDE240072002 (accessed May 20, 2010); and George, Syria: neither Bread nor Freedom, pp. 47-63. 12 See, for example, Joshua Landis, “The United States and Reform in Syria,” March 2004, http://www.ou.edu/ssa/US_Syrian_Reform.htm (accessed July 5, 2010) arguing that “[o]pposition members immediately demanded free elections and regime change, forcing Bashar to crack down on them.” 13 Eyal Zisser, “Does Bashar al-Assad Rule Syria?,” Middle East Quarterly, Winter 2003, http://www.meforum.org/517/does- bashar-al-assad-rule-syria (accessed July 5, 2010), para. 3.5. A Wasted Decade 6

- 11. Dr. Kamal Labwani: Sentenced to 12 Years in Jail for Demanding Reform Dr. Kamal al-Labwani, a physician and founder of the Democratic Liberal Gathering, was sentenced in May 2007 to 12 years in prison for “communicating with a foreign country and inciting it to initiate aggression against Syria” after he visited the United States and Europe in the fall of 2005, where he met with government officials, journalists and human rights organizations. During his trip, he appeared on the pan-Arab Al-Mustaqilla and Al-Hurra television networks, where he called on the Syrian government to respect fundamental freedoms and human rights. The 12-year sentence is the harshest sentence against a political activist since al-Asad took power. Labwani received an additional three- year sentence on April 28, 2008, for “insulting the authorities” while in detention.14 In March 2009 the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the body mandated with investigating complaints of arbitrary deprivation of liberty, stated that Labwani’s imprisonment since November 2005 constituted arbitrary detention. The Working Group concluded that Labwani “had been condemned for the peaceful expression of his political views and for having carried out political activities” that are protected under international law. It also deemed that his trial was unfair.15 The Democratic Liberal Gathering is an unregistered group of Syrian intellectuals and activists who advocate for peaceful change in Syria based on democratic reforms, liberalism, secularism and respect for human rights. Arrests and trials are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Syria’s harassment of dissidents. Syrian security services routinely prohibit or interrupt meetings and press conferences by political activists, civil society, and human rights groups.16 The Syrian Bar Association has also harassed human rights lawyers by initiating disciplinary measures to disbar lawyers who criticize the government or the president’s policies. On November 10, 2009, the bar association’s disciplinary tribunal issued a decision to permanently disbar Muhanad al-Hasani, President of the Syrian Human Rights Organization (Swasiah), because he “headed an unlicensed human rights organization without obtaining 14 “Syria: Rights Activist Detained After Travel Abroad,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 17, 2005, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2005/11/17/syria-rights-activist-detained-after-travel-abroad.; “Syria: Peaceful Activist Gets 12 Years With Hard Labor,” Human Rights Watch news release, May 10, 2007, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2007/05/10/syria- peaceful-activist-gets-12-years-hard-labor. 15 “Syria: UN Rules Dissident’s Detention Illegal,” Human Rights Watch joint news release, April 29, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/04/29/syria-un-rules-dissident-s-detention-illegal. 16 For more information on disrupting meetings and gatherings of human rights defenders see Human Rights Watch, No Room to Breathe: State Repression of Human Rights Activism in Syria, vol. 19, no. 6(E), October 2007, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2007/10/16/no-room-breathe-0, Part V. 7 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 12. the prior approval of the bar association” and “attended sessions of the State Security Court to monitor its proceedings without being appointed as a defense lawyer by the accused.”17 Syrian authorities also use travel bans as punishment for activists and dissidents. The use of such bans has expanded dramatically since 2006. The Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, an unlicensed non-governmental organization (NGO), issued a report in February 2009 listing 417 political and human rights activists banned from traveling. In some cases, the ban extended to the families of the activists.18 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Syria ratified in 1969, requires all states to ensure that everyone has the right to leave any country, including their own. The only permissible restrictions are those “provided by law” and that “are necessary to protect national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Covenant” (including the right to freedom of expression and association).19 In this case, the bans imposed on these activists are tied simply to their political expression, and not based on any defined security interests. Syrian authorities deny all requests by human rights groups to register, and accordingly none are officially authorized to exist. The main impediments to their registration is the 1958 Law on Associations and Private Societies (Law No. 93), which governs the establishment of any type of association or organization in Syria and authorizes the security services to refuse the registration request of these groups.20 The systematic denial of registration of human rights groups has direct negative implications on their activities, allowing the government to arrest members for participation in an “illegal organization,” and to ban meetings or events. A human rights lawyer told Human Rights Watch that the “lack of registration is like a sword over our necks. The mukhabarat [secret services] can act on it whenever they want.”21 In 2005 the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor, the ministry officially responsible for administering Law No. 93, said that it would review the law with an eye toward liberalizing 17 “Syria: Restore Jailed Lawyer’s Credentials,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 13, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/11/13/syria-restore-jailed-lawyer-s-credentials. 18 Syrian Center for Media & Freedom of Expression, Problematic of the Travel Ban in Syria, http://www.scm- sy.org/?page=category&category_id=22&lang=en (accessed June 14, 2010). See also “Syria: Civil Society Activists Barred from Traveling,” Human Rights Watch news release, July 11, 2006, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2006/07/11/syria-civil- society-activists-barred-traveling. 19 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No.16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, article 12. 20 For a detailed analysis of the legal framework for registration, see Human Rights Watch, No Room to Breathe, Part IV. 21 Human Rights Watch interview with human rights lawyer (name withheld), Damascus, November 17, 2006. A Wasted Decade 8

- 13. its provisions.22 However, the drive to reform the existing law came to a complete stop shortly thereafter, without any explanation. Were the Syrian authorities responding to outside pressure to open up, or were there elements inside the government pushing for reforms? Syria’s opaque politics and lack of public debate about policy choices make it impossible to really know what drove these decisions. Five years later, First Lady Asma al-Asad opened a conference in Damascus in January 2010 by declaring that the state “wanted to open more space for civil society to work, develop and partner with the government and implement development-oriented policies.” She said, “We will learn from our mistakes and a law will be passed soon—after consultation with civil society—to provide non-governmental organizations (NGOs) the safeguards they need to operate effectively.”23 However, no draft law has been made public, and it is not clear whether the Syrian authorities will allow independent and human rights NGOs to officially register or whether they will limit any easing of the law to NGOs that assist the government in its “development-oriented policies.” The combination of these laws and practices has kept Syria’s human rights activists in constant fear of being detained. As one human rights lawyer told Human Rights Watch recently, “I cannot go on like this. I keep getting called in for interrogation. Every time I go, I don’t know if I will be detained or not.”24 Political activists in Syria are also still awaiting a new law for political parties following al- Asad’s March 2005 declaration to a group of Spanish journalists that “the coming period will be one of freedom for political parties” in Syria.”25 In June 2005, the Ba`ath Party Congress recommended the passing of a new political party law that would allow the creation of non- ethnic and non-religious political parties.26 However, to date, there is still no new draft law for the creation of political parties. 22 For more details about the attempts to reform the law, see Human Rights Watch, No Room to Breathe, Part IV. 23 Cited in Rami Khouri, “Signals of Change from Syria,” Agence Global, January 27, 2010, http://www.agenceglobal.com/article.asp?id=2244 (accessed June 10, 2010). While there is growing recognition in Syria of the role of NGOs in development, these NGOs are closely tied to the authorities and they are being introduced to fill the gap left by the weakness of the state bureaucracy and local administration. The First Lady, Asma al-Asad plays a key role in that respect with a series of government-allied NGOs that are grouped under an entity called Syria Trust. However, these recent initiatives so far appear more as an effort by the regime to gain legitimacy and to further the objectives of the state, as opposed to efforts to foster an independent civil society. 24 Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Syrian human rights activist (name withheld), May 23, 2010. 25 Sami Moubayed, “Syria's Ba`athists Loosen the Reins,” Asia Times, April 26, 2005, http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/GD26Ak04.html (accessed May 12, 2010). 26 Rhonda Roumani, “In Syria, democrats chomp at bit,” Christian Science Monitor, September 23, 2005, http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0923/p06s03-wome.html (accessed May 12, 2010). 9 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 14. Accordingly, we urge President al-Asad to: • Lift the state of emergency and repeal Syria’s Emergency Law. The continued application of the Emergency Law since 1963 violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Syria is a party. The Syrian government has failed to show that the state of emergency is strictly necessary for its security. Release all individuals currently deprived of their liberty for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression, association, or assembly. • Order the security services to cease detaining activists and banning them from traveling abroad merely for exercising their legitimate right to freedom of expression and association. • Enact a political parties law in compliance with international human rights norms, and establish an independent electoral commission to register new political parties. • Amend the 1958 Law on Associations and Private Societies (Law No. 93) to ensure that groups formed for any legal purpose are allowed to acquire legal personality by making registration of associations automatic once these associations fulfill the formal requirements and by abolishing penalties for participation in unregistered associations if such associations are not otherwise breaking the law. A Wasted Decade 10

- 15. II. Restrictions on Freedom of Expression The Ba`ath party banned all independent publications after it came to power in 1963, and for the following 40 years only three newspapers existed in Syria, all of which were affiliated with the party: al-Ba`ath (the party’s official mouthpiece since 1947), al-Thawra (a 1963 Ba`ath daily meaning “revolution”), and Tishreen (a 1973 Ba`ath daily).27 After Bashar al-Asad assumed power, he removed the outright ban on independent publications, but introduced a new Press Law (Decree No. 50/2001), promulgated on September 22, 2001, which provided the government with sweeping control over newspapers, magazines, and other periodicals, as well as virtually anything else printed in Syria, from books to pamphlets and posters. Provisions apply to publishers, editors, journalists, authors, printers, distributors, and bookstore owners, and subject them to imprisonment and steep fines for violations of the law.28 Initially, the authorities mostly granted licenses to economic and cultural publications, or to political newspapers issued by individuals or parties close to the Ba`ath party, such as the Communist Party which received a license to publish a weekly entitled Sawt al-Shaab (Voice of the People) in February 2001.29 The most promising development was the granting that same month of a license to Addomari (the Lamp Lighter), a satirical publication published by renowned Syrian cartoonist Ali Farzat. The newspaper was an instant success as it was the first Syrian newspaper in 40 years that printed something different from the views of the Ba`ath party or those of its close allies. With a circulation of 75,000, it sold many times more than the three “official” dailies, but the government closed it down in 2003 after officials 27 Teshreen and al-Thawra are published by the Unity Institution for the Press, Publication and Printing (Mu’assasat al-wihda lil-sahafa wa al-tiba`at wa al-nashar) whose board is appointed by the Prime Minister. See, for example, the decision by Prime Minister `Otari to appoint the board on April 11, 2007: “Al-Jarrad is President of the Administrative Board for the Unity Institution for the Press, Publication, Printing, and Distribution,” SANA News Agency, April 11, 2007, http://furat.alwehda.gov.sy/_archive.asp?FileName=47329122220070410233947 (accessed July 5, 2010). 28 A fuller analysis of the 2001 Press Law is available in Human Rights Watch, Memorandum to the Syrian Government, Decree No. 51/2001: Human Rights Concerns, January 31, 2002. 29 Sawt al-Shaab had been outlawed since 1958. In contrast to the decision to grant a license to republish Sawt al-Shaab, the Syrian government turned down in 2001 two applications to re-launch popular independent newspapers that existed prior to the Ba`ath’s arrival to power in 1963: al-Qabas (The Firebrand) and al-Ayyam (The Times). For more information on developments affecting the press in Syria in 2001, see Sami Moubayed, “Independent Journalism Slowly Returning to Syria,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, July 2001, http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:34rNEM_7W7MJ:www.wrmea.com/archives/july01/0107036.html+ ba`ath+in+syria+independent+newspaper&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=lb (accessed June 10, 2010). 11 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 16. told its founder, Ali Farzat, that he “went too far.”30 His publication had criticized Saddam Hussein by showing him and his generals stuffing the Iraqi people as cannon fodder in the face of the impending US invasion, at a time when the Syrian government’s policy was to oppose the invasion of Iraq.31 Censorship remains widespread. The Arab Establishment for Distribution of Printed Products, which is affiliated with the Ministry of Information, vets all newspapers prior to distribution. Syria’s two private daily newspapers covering political topics that have succeeded in staying open are owned by businessmen closely tied to the regime: al-Watan, launched in November 2006, is a daily political newspaper widely reported to be published by President al-Asad’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf; Baladna, a social affairs newspaper, is published by Majd Suleiman, son of security chief General Bahjat Suleiman.32 On July 13, 2005, Nizar Mayhoob, a spokesman for the Syrian Ministry of Information, told Human Rights Watch that Syria would issue a new media law, “which will enhance the [press] law issued in 2001 by overcoming its inadequacies.” Al-Asad himself, in his second inaugural speech on July 18, 2007, noted that: On the media law, the subject has been raised many times. There is a recent proposal by the Ministry of Information on the need to amend the media law. I heard many complaints from journalists and others that they are not happy with the existing law. There could be proposals from the Ministry of Information in this regard which could be studied by the People’s Assembly, and the law could be passed. 33 As of July 6, 2010, no new law had been introduced and there is still no independent press in Syria. 30 For more information about Addomari, including interviews with its founder Ali Farzat, check Dan Isaacs, “Hoping for Media Freedom in Syria,” BBC News Online, March 25, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/4381739.stm (accessed June 10, 2010). 31 David Hirst, “Saddam No Longer a Joke for Syrian Satirist,” The Guardian, August 21, 2003, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2003/aug/21/syria.davidhirst (accessed June 10, 2010). 32 For Makhlouf’s role in publishing al-Watan, see for example, International Research and Exchanges Board, Media Sustainability Index (MSI) - Middle East & North Africa (MENA), Syria, 2008, http://www.irex.org/programs/MSI_MENA/2008/MSIMENA_syria.asp (accessed July 4, 2010). Baladna is published by United Group for Publishing, Advertising and Marketing, which is chaired by Majd Suleiman, see company website: http://www.ug.com.sy/chairman-letter.html (accessed on July 4, 2010). 33 Bashar al-Asad’s Second Inaugural Address on July 18, 2007, available at http://www.mideastweb.org/bashar_assad_inauguration_2007.htm (accessed on June 10, 2010). A Wasted Decade 12

- 17. Instead, the government has extended restrictions it imposes on print media to online outlets, reversing early hopes that al-Asad’s role as chairman of the Syrian Computer Society (SCS) prior to his appointment as president would make him more receptive to freedom of expression online. OpenNet Initiative, a partnership of four leading universities in the US, Canada, and the UK, which monitors government filtration and surveillance of the internet, says that filtering of political websites in Syria is “pervasive.” Internet censorship extends to popular websites such as Blogger (Google’s blogging engine), Facebook, and YouTube.34 The authorities have also prosecuted journalists, bloggers, and citizens who dare criticize the authorities or the president. The vast majority of journalists and bloggers have been tried before the State Security Court (SSSC), an exceptional court with almost no procedural guarantees. In 2009, the Committee to Protect Journalists named Syria number three on a list of the ten worst countries in which to be a blogger based on the arrests, harassments, and restrictions that online writers in Syria have faced.35 Human Rights Watch found that between January 2007 and June 2008, the SSSC sentenced at least 10 writers and bloggers who had criticized the authorities, and that overall the court convicted 153 defendants on the basis of overbroad security provisions (described in Section 1 above) that violate basic rights to freedom of expression. In one case, the SSSC sentenced Muhamad Walid al- Husseini, 67, to three years in prison because a member of the security services overheard him insult the Syrian president and criticize the country’s corruption while sitting at a popular café in Syria.36 34 OpenNet Initiative, Syria, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/syria (accessed June 15, 2010); Khaled Yacoub Oweis, “Syria blocks Facebook in Internet crackdown,” Reuters, November, 23, 2007, http://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUSOWE37285020071123. 35 Committee to Protect Journalists, “10 Worst Countries to be a Blogger,” April 30, 2009, http://www.cpj.org/reports/2009/04/10-worst-countries-to-be-a-blogger.php (accessed June 10, 2010). 36 For more information see Human Rights Watch, Far From Justice: Syria’s Supreme State Security Court, 1-56432-434-6, February 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2009/02/23/far-justice, p. 35. 13 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 18. Table 1. Known Journalists and Bloggers Detained During Bashar al-Asad’s First Decade in Power37 Name Date of Arrest and Context Charges/Sentence/Outcome Ibrahim Detained on December 23, 2002, Charged with “publishing unfounded news,” a Hamidi, after publishing article reporting that violation of Article 51 of the 2001 Publication journalist at al- Syria was preparing to receive one Law. He was released on bail on May 25, Hayat million Iraqi refugees in the event of a 2003. SSSC finally ruled on April 10, 2005, war in Iraq. that it did not have sufficient evidence to proceed with the case. Two sisters Detained in 2002. Charged with “obtaining information that `Aziza and should be kept confidential for the integrity of Shireen al- the state.” Aziza Sabini was also charged with Sabini, who “promoting news that may weaken the morale both worked of the nation.” The SSSC later sentenced them for al-Muharir to one year in prison. al-`Arabi newspaper `Abdel Rahman Detained on February 23, 2003. SSSC sentenced him to two and a half years in al-Shaghouri, prison on June 20, 2004 for “disseminating online false information” via the internet. He was journalist for released on August 31, 2005. the opposition website Levant News Muhannad and Detained in September 2002 for SSSC sentenced them in July 25, 2004, for Haytham sending e-mails to a UAE based “receiving secret information on behalf of a Qutaysh, and newspaper about the reported death foreign state that threatens the security of Yahya al-Aws of two construction workers in Syria,” using the internet to publish “false Damascus. news outside of Syria” under the Press Law, and “encouraging the transfer of secret information.” The court further found Haytham Qutaish guilty of “writing that threatens the security of Syria and her relations with foreign states.” The sentences ranged from two to four years in prison. 37 The table is based on multiple sources of information, including interviews with journalists, Syrian human rights activists, as well as a review of press releases by Syrian and other international human rights groups. For more information on arrest of bloggers, see Human Rights Watch, False Freedom: Online Censorship in the Middle East and North Africa (New York: Human Rights Watch, 1995), http://www.hrw.org/en/node/11563/section/7, section 7. A Wasted Decade 14

- 19. Name Date of Arrest and Context Charges/Sentence/Outcome Mas`ud Hamed Detained on July 24, 2003, after he The SSSC sentenced him on October 10, posted online photographs of police 2004, to three years in prison, after finding violently dispersing a demonstration him guilty of “membership in a secret of Syrian Kurdish children in front of organization” and “attempting to annex part UNICEF’s offices in Damascus. of Syrian territory to another country.” Ali Zein al- Detained on October 9, 2005, after he The SSSC sentenced him on September 23, `Abideen posted comments online attacking 2007, to two years in prison for “undertaking Mej`an Saudi Arabia. actions or writing or making speeches unauthorized by the government ... that spoil its ties with a foreign state.” Omar al- Detained between January and March The SSSC sentenced the group to sentences Abdullah, 2006 after developing a youth varying from five to seven years in jail for Tarek Ghorani, discussion group and publishing “taking action or making a written statement Maher Ibrahim certain articles online that were that could endanger the State or harm its Asper, Ayham critical of Syrian authorities. relationship with a foreign country.” Saqr, `Ulam Fakhour, Diab Siriya, and Husam Melhem Muhammad Arrested on March 31, 2006, A military court found him guilty of insulting Ghanem, reportedly for articles he had written the president, undermining the state’s online advocating political and cultural dignity, and inciting sectarian divisions; it journalist and rights for Syria’s Kurdish minority and sentenced him to six months in jail. editor of the for criticizing the Ba`ath Party’s news website handling of domestic issues. Ghanem Surion. was previously arrested and detained for 15 days by military intelligence in March 2004. Firas Sa`ad, Detained on July 30, 2006, after he On April 7, 2008, the SSSC sentenced him to writer and poet published articles on the website four years in jail for “weakening national www.ahewar.org, in which he sentiment.” defended a call for improved relations between Lebanon and Syria and criticized the Syrian army’s role in the July 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah. 15 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 20. Name Date of Arrest and Context Charges/Sentence/Outcome Ali Sayed al- Detained on August 10, 2006, Released pursuant to amnesty on January 9, Shihabi, following a number of articles he 2007, before his trial concluded. English teacher published on the website and writer www.rezgar.com, including one in which he called for the creation of a new political party called “Syria for all.” Muhanad Both were arrested in September Charged with Art. 287 (spreading false Abdel-Rahman 2006 while conducting an information) before a military court. Charge and `Ala’ al- investigation of the state of labor eventually set aside as part of General Deen unions in Syria. Amnesty No. 56 of September 2007. Both Hamdoun, were released in September 2007. journalists Karim `Arbaji Detained in June 2007 for moderating The SSSC sentenced him to three years in a popular online youth forum, prison on September 13, 2009, for “spreading akhawia.net, that included criticisms false information that can weaken national of the government. sentiment.” Tariq Biasi, Arrested in July 2007after he posted The SSSC sentenced him to three years blogger and critical comments about the security imprisonment on May 11, 2008, on charges of son of former services on a website “weakening national sentiment” and political “spreading false news”. prisoner Mazen Arrested on January 12, 2008, for A military court sentenced him on June 23, Darwish, reporting on violent clashes in the 2008, to five days in jail. journalist and Damascus suburb of `Adra. president of the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression Abdullah Ali Detained on July 30, 2008, for 13 No charges brought. Suleiman, days after authorities shut down his publisher of website. the website Nazaha.com A Wasted Decade 16

- 21. Accordingly, we urge President Bashar al-Asad to: • Immediately and unconditionally release all those imprisoned or detained solely for exercising their right to free expression, online or otherwise. • Stop blocking websites for their content. • Introduce a new media law that would remove all prison penalties for defamation and libel; stop government censorship of local and foreign publications; and remove government control over newspapers and other publications. • Amend or abolish the vague provisions of the Syrian Penal Code that permit the authorities to arbitrarily suppress and punish individuals for peaceful expression, in breach of its international legal obligations, on grounds that “national security” is being endangered, including the following provisions: Article 278 (undertaking “acts, writings, or speech unauthorized by the government that expose Syria to the danger of belligerent acts or that disrupt Syria’s ties to foreign states”), Article 285 (“issuing calls that weaken national sentiment or awaken racial or sectarian tensions while Syria is at war or is expecting a war”), Article 286 (spreading “false or exaggerated information that weaken national sentiment while Syria is at war or is expecting a war”), Article 307 (undertaking “acts, writings or speech that incite sectarian, racial or religious strife”), and Article 376 (which imposes a sentence from one to three years on anyone who insults the president). 17 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 22. III. Torture, Ill-Treatment, and Enforced Disappearances Bashar al-Asad raised hopes for change with respect to the treatment of detainees when he took two significant steps: closing the Mazzeh prison in November 2000, which held numerous political prisoners, and transferring approximately 500 political detainees during July-August 2001 from the notorious Tadmor prison, in Syria’s eastern desert, to Sednaya prison, north of Damascus, which was considered to offer better facilities. Al-Asad never explained his decision to transfer political prisoners out of Tadmor, but Syrian activists saw the move as a hopeful sign given Tadmor’s association with government repression of the 1980s. Human Rights Watch has documented extensive human rights abuse, torture, and summary executions in Tadmor prison, a facility used to detain thousands of political prisoners in the 1980s; it was also the scene in June 1980 of the extrajudicial killings of an estimated 1,000 prisoners by commando units loyal to Rif`at al- Asad, Hafez al-Asad’s brother (see more on Tadmor prison massacre in Section 5).38 Faraj Beraqdar, a Syrian poet and five-year inmate in Tadmor, described the prison as “the kingdom of death and madness.”39 But while closing Tadmor prison was a promising sign of detention reform, it has not led to other positive improvements. Bashar al-Asad has done nothing to get rid of the practices of incommunicado detention, ill-treatment, and torture during interrogation, which remain common in Syria’s detention facilities. Syria’s security services regularly hold detainees incommunicado—cut off from all contact with family, a lawyer, or any other link with the outside world— for days, months, and in some cases, years. For example, in August 2008, Syrian security forces detained a group of 13 young men from the northeastern district of Deir al-Zor suspected of having ties to Islamists. To this day, the authorities have not disclosed where they are holding at least 10 of the men, why they arrested them, or whether they will charge them and put them on trial. Prison officials returned the body of one of those detained in Deir al-Zor, Muhammad Amin al-Shawa, 43, to his family on January 10, 2009, but they allowed them to see only his face 38 See Middle East Watch (now Human Rights Watch/MENA), Syria Unmasked: The Suppression of Human Rights by the Asad Regime (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. 54-78; Human Rights Watch, Syria's Tadmor Prison: Dissent Still Hostage To a Legacy of Terror, vol. 8, no. 2(E), April 1996, http://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Syria2.htm. 39 Beraqdar used this term in a lengthy defense memorandum that he submitted to the state security court during his trial. The court sentenced him to a fifteen-year prison term in October 1993. A Wasted Decade 18

- 23. before burying him. Three Syrian human rights activists told Human Rights Watch that they believe that al-Shawa died due to torture.40 Human Rights Watch and other human rights groups have also documented a frequent pattern of torture and other ill‐treatment by Syria’s security services of political and human rights detainees as well as criminal suspects.41 Out of 30 former Kurdish detainees held after 2004 and interviewed by Human Rights Watch following their release, 12 said that security forces tortured them.42 Human Rights Watch has also documented the torture of bloggers and beatings of prominent political activists by government security agents. For example, eight of the twelve detainees from the Damascus Declaration for Democratic Change, an umbrella group of opposition and pro-democracy groups, detained in December 2007, told their investigative judge that state security agents had beaten them during detention. 43 The UN Committee against Torture, which is tasked with monitoring compliance with the Convention against Torture, said in May 2010 that it was “deeply concerned about numerous, ongoing and consistent allegations concerning the routine use of torture by law enforcement and investigative officials…”44 An official Canadian Commission of Inquiry into the 2002 US deportation to Syria of Maher Arar, a Syrian-born Canadian, concluded that “the SMI [Syrian Military Intelligence] tortured Mr. Arar while interrogating him during the period he was held incommunicado at the SMI’s Palestine Branch facility.”45 In an encouraging step in detainee practices, Bashar al-Asad’s government ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment on July 1, 2004. However, it has not followed the ratification with concrete measures to end 40 For more background, see “Syria: Reveal Fate of 17 Held Incommunicado,” Human Rights Watch news release, April 15, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/04/15/syria-reveal-fate-17-held-incommunicado; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with relative of one of the Deir al-Zor detainees, June 10, 2010. 41 See, for example, Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies, Alternative Report to the Syrian Government’s Initial Report on Measures Taken to Fulfill its Commitments under the Convention against Torture, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cat/docs/ngos/DCHRS.pdf (accessed June 15, 2010), p.3.; Amnesty International, Briefing to the Committee against Torture, AI Index: MDE 24/008/2010, April 20, 2010, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/MDE24/008/2010/en (accessed June 15, 2010); Al-Karama, Syria: Permanent State of Emergency – A Breeding Ground for Torture, April 9, 2010, http://en.alkarama.org/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_details&gid=169&Itemid=80 (accessed June 15, 2010). 42 For more details, see Human Rights Watch, Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria, 1- 56432-560-1, November 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2009/11/24/group-denial, pp. 45-49. 43 “Syria: Opposition Activists Tell of Beatings in Interrogation,” Human Rights Watch news release, February 4, 2008, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/02/04/syria-opposition-activists-tell-beatings-interrogation; 44 UN Committee against Torture, Concluding Observations of the Committee against Torture, CAT/C/SYR/CO/1 (adopted on May 3-4, 2010), http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cat/docs/CAT.C.SYR.CO.1.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010), para. 7. 45 Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in Relation to Maher Arar, Report of the Events Relating to Maher Arar, 2006, http://www.sirc-csars.gc.ca/pdfs/cm_arar_rec-eng.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010), p. 187. 19 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 24. the practice of torture, such as investigations of allegations of torture or permission for independent observers to visit Syria’s prisons and detention facilities. According to the Syrian submission to the Committee Against Torture (CAT), the Syrian Minister for Internal Affairs issued Circular No. 10 dated December 16, 2004, requesting members of the police to hold meetings to “familiarize themselves with the prohibitions on the use of violence against persons on remand and prisoners and to receive instructions on performing their duties in a responsible manner. Successful investigators can arrive at the desired result using proper scientific and technical methods to establish the facts of a case without needing to resort to illegal methods.”46 In their submission, the Syrian delegation mentioned six cases where police were held liable for torturing people.47 However, such cases remain exceptions; they are limited to the police force and not the security services, which benefit from extensive legal immunity for acts of torture. Legislative Decree No. 14, of January 15, 1969, which established the General Intelligence Division (Idarat al-Mukhabaraat al-`Ama), one of Syria’s largest security apparatuses, provides that “no legal action may be taken against any employee of General Intelligence for crimes committed while carrying out their designated duties … except by an order issued by the Director.” To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, the director of General Intelligence has issued no such order to date. On September 30, 2008, al-Asad issued Legislative Decree 69, which extended this immunity to members of other security forces, by requiring a decree from the General Command of the Army and Armed Forces to prosecute any member of the internal security forces, Political Security, and customs police.48 Syria’s courts continue to accept confessions obtained under torture. For example, Human Rights Watch’s review of trials in the SSSC in 2007 and 2008 revealed that 33 defendants alleged before the judge that they had been tortured and that the security services had extracted confessions from them by force, but in no case did the SSSC take any measure to open an investigation into these claims.49 When human rights lawyers allege that their clients have been tortured, they risk being prosecuted for “spreading false information,” a criminal charge. For example, on April 24, 46 Syrian Arab Republic, Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties under Article 19 of the Convention, CAT/C/SYR/1, July 20, 2009, para. 79. 47 Syrian Arab Republic, Initial Submission to CAT, Paras. 82-83. 48 For further in depth analysis of these provisions, see Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies, Alternative Report, pp. 6- 8. 49 Human Rights Watch, Far From Justice, pp. 27-32. A Wasted Decade 20

- 25. 2007, a Damascus criminal court sentenced human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni to five years in prison for alleging that a man had died in a Syrian jail because of its inhumane conditions.50 More recently, on June 30, 2010, a Damascus criminal court sentenced another prominent human rights lawyer, Muhanad al-Hasani, to three years in prison because he publicly denounced the alleged death of a detainee under torture and criticized the SSSC.51 Syria’s prison facilities are still off-limits to independent observers, and Syrian authorities continue to impose a blackout on information concerning the deadly shooting of as many as 25 inmates by military police in Sednaya prison on July 5, 2008. Deadly Shooting in Sednaya Prison Prison authorities and military police used firearms to quell a riot that began on July 5, 2008, at Sednaya prison, about 30 kilometers north of Damascus. The prison holds at least 1,500 inmates and possibly as many as 2,500. Human Rights Watch obtained the names of nine inmates who are believed to have been killed in a standoff between the prisoners and authorities that reportedly lasted for many days. Syrian human rights organizations have reported that the number of inmates who were killed may be as high as 25. One member of the military police was also confirmed to have been killed. The government imposed a total blackout on the events and has not released any information about the action its forces took against the prisoners, or any investigation it may have carried out regarding the violence at the prison. In July 2009 the authorities finally allowed some families to visit relatives in the prison but have maintained a ban on visits by others and on information about other detainees. In December 2009 Human Rights Watch released a partial list of 42 Sednaya detainees whose families have not been able to get any information about them.52 To date, they still have not received any information. 50 “Syria: Harsh Sentence for Prominent Rights Lawyer,” Human Rights Watch news release, April 24, 2007, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2007/04/24/syria-harsh-sentence-prominent-rights-lawyer. In a previous incident in November 2002, Judge al-Nuri, the head of SSSC, ejected lawyer Anwar al-Bunni from the courtroom after he insisted on an investigation into claims that the security apparatus had tortured his client, Aref Dalila, during his detention. 51 “Syria: Detained Lawyer Receives Martin Ennals Award,” Human Rights Watch news release, May 7, 2010, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2010/05/07/syria-detained-lawyer-receives-martin-ennals-award. 52 “Syria: Investigate Sednaya Prison Deaths,” Human Rights Watch news release, July 21, 2008, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/07/21/syria-investigate-sednaya-prison-deaths; “Syria: Lift Blackout on Prisoners’ Fate,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 10, 2009, http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2009/12/10/syria-lift-blackout- prisoners-fate. 21 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 26. Aerial view of Sednaya prison. Accordingly, we urge President Bashar al-Asad to: • Order an independent investigation into torture allegations and make public the results of the investigation. Discipline or prosecute, as appropriate, officials responsible for the mistreatment of detainees, including those who gave orders or were otherwise complicit, and make public the results of the punishment. • Adopt effective measures to ensure that all detainees have prompt access to a lawyer and an independent medical examination. • Allow independent outside observers access to prisons and detention facilities. • Order an independent investigation into the deadly shooting of inmates by military police at Sednaya prison and make the findings public. • Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT), and invite its Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture to visit and inspect Syria’s places of detention. A Wasted Decade 22

- 27. IV. Repression of Kurds Kurds are the largest non-Arab ethnic minority in Syria; estimated at approximately 1.7 million, they make up roughly 10 percent of Syria’s population. Since the 1950s, successive Syrian governments have pursued a policy of repressing Kurdish identity because they perceived it to be a threat to the unity of an Arab Syria. Under Bashar al-Asad, Syrian authorities have continued to suppress the political and cultural rights of the Kurdish minority, including banning the teaching of Kurdish in schools and regularly disrupting gatherings to celebrate Kurdish festivals such as Nowruz (the Kurdish New Year). Harassment of Syrian Kurds increased further after they held large-scale demonstrations, some violent, throughout northern Syria in March 2004 to voice long-simmering grievances. Syrian authorities reacted to the protests with lethal force, killing at least 36 people, injuring over 160, and detaining more than 2,000, amidst widespread reports of torture and ill- treatment of detainees. Most detainees were eventually released, including 312 who were freed under an amnesty announced by al-Asad on March 30, 2005. However, since then, the Syrian government has maintained a policy of banning Kurdish political and cultural gatherings. Human Rights Watch has documented the repression of at least 14 Kurdish political and cultural gatherings since 2005. The security forces also have detained a number of leading Kurdish political activists and referred them to military courts or the SSSC for prosecution under charges of “inciting strife” or “weakening national sentiment.”53 In addition, large numbers of Kurds are stateless and consequently face a range of difficulties, from getting jobs and registering weddings to obtaining state services. In 1962, an exceptional census stripped some 120,000 Syrian Kurds—20 percent of the Syrian Kurdish population—of their Syrian citizenship. By many accounts, the special census was carried out in an arbitrary manner. Brothers from the same family, born in the same Syrian village, were classified differently. Fathers became foreigners while their sons remained citizens. The number of stateless Kurds grew with time as descendants of those who lost citizenship in 1962 multiplied; as a result, their number is now estimated at 300,000.54 53 For more details on the repression of Kurdish activism following the 2004 riots, see Human Rights Watch, Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria. 54 For a review of the stateless Kurds’ situation, see Human Rights Watch, Syria: The Silenced Kurds, vol. 8, no. 4(E), October 1996, http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/1996/10/01/syria-silenced-kurds; Maureen Lynch and Perveen Ali, Refugees International, “Buried Alive: Stateless Kurds in Syria,” January 2006, http://www.refugeesinternational.org/sites/default/files/BuriedAlive.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010); Kurd Watch, Stateless Kurds in Syria: Illegal Invaders or Victims of a Nationalistic Policy?, Report 5, March 2010, http://yasa- online.org/reports/kurdwatch_staatenlose_en.pdf (accessed June 10, 2010). 23 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 28. Al-Asad has repeatedly promised Kurdish leaders a solution to the plight of the stateless Kurds, but a decade later, they are still waiting. He first promised to tackle the issue when he visited the largely Kurdish-populated region of al-Hasaka on August 18, 2002, and met with a number of Kurdish leaders.55 In his second inaugural speech on July 17, 2007, he mentioned the promise he made in 2002, but noted that political developments had prevented progress in this area: I visited al-Hasaka governorate in August 2002 and met representatives of the community there. All of them without exception talked about this issue [the 1962 census]. I told them, “we have no problem, we will start working on it.” That was the time when the United States was preparing to invade Iraq.… We started moving slowly, the Iraq war happened, and there were different circumstances which stopped many things concerning internal reform. In 2004, the riots in al-Qamishli governorate happened, and we did not exactly know the background of the riots, because some people took advantage of the events for non-patriotic purposes.… We restarted the process last year on the government’s initiative since the events have gone and it was shown that there were no non-patriotic implications.56 Later in his speech, al-Asad referred to a draft law that would solve the problem for some stateless Kurds, namely those who became stateless even though other members of their family obtained citizenship.57 He concluded by saying that “the consultations continue…and when we are done with those…the law is ready.” Three years later, and despite the fact that the political justifications for the delays have long ceased to exist, there is no new law, and no steps have been taken to address Kurdish grievances. Accordingly, we urge President Bashar al-Asad to: • Set up a commission tasked with addressing the underlying grievances of the Kurdish minority in Syria and make public the results of its findings and 55 Human Rights Watch interview with Kurdish political activist in Azadi party, Damascus , November 1, 2009; Human Rights Watch interview with Kurdish political activist in Yekiti party, Ras al-Ain, October 6, 2009; Kurd Watch, Stateless Kurds in Syria, pp. 21-22. 56 Bashar al-Asad second inaugural speech, July 17, 2007, available at http://www.mideastweb.org/bashar_assad_inauguration_2007.htm (accessed June 10, 2010). 57 Ibid. He indicated that the law would not grant any rights to those who are considered Maktumee, stateless Kurds who are not listed on any register in Syria. A Wasted Decade 24

- 29. recommendations. The commission should include members of Syria’s Kurdish political parties. • Redress the status of all Kurds who were born in Syria but are stateless by offering citizenship to any person with strong ties to Syria by reason of birth, marriage, or long residence in the country and who is not otherwise entitled to citizenship in another country. • Identify and remove discriminatory laws and policies on Kurds, including reviewing all government decrees and directives that apply uniquely to the Kurdish minority in Syria or have a disproportionate impact on them. • Ensure that Syria’s Kurds have the right to enjoy their own culture and use their own language; likewise, ensure freedom of expression, including the right to celebrate cultural holidays and learn Kurdish in schools. • Invite the UN Independent Expert on Minority Issues to visit Syria. 25 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 30. V. Legacy of Enforced Disappearances Bashar al-Asad inherited a country with a legacy of abusive practices, but to date he has not taken any concrete steps to acknowledge and address these abuses or shed light on the fate of thousands of people who have disappeared since the 1980s. Syria’s security forces were involved in gross human rights violations in the late 1970s and 1980s in an effort to quell opposition to Hafez al-Asad’s regime, including armed opposition by certain segments of the Muslim Brotherhood. The security forces detained and tortured thousands of members of the Muslim Brotherhood, communist and other leftist parties, the Iraqi Ba`ath party, Nasserite parties, and different Palestinian groups—many of whom subsequently disappeared. While no exact figures exist, various researchers estimate the number of the disappeared to be 17,000 persons.58 Syria’s armed forces and security services also detained and abducted Lebanese, Palestinians, and other Arab nationals during Syria’s military presence in Lebanon, hundreds of whom are still unaccounted for. On June 27, 1980, commandos from the Defense Brigades under the command of Rif`at al- Asad, Hafez al-Asad’s brother, killed an estimated 1,000 unarmed inmates, mostly Islamists, at Tadmor military prison, in retaliation for a failed assassination attempt against Hafez al- Asad.59 The names of those killed were never made public. Less than two years later, from February to March 1982, commandos from the Defense Brigades and units of the Special Forces circled the city of Hama, Syria’s fourth largest town and an opposition stronghold, and engaged in heavy fighting against Islamists opposed to the regime. The Syrian security troops committed large scale human rights violations during the fighting, including the killing of hundreds of people in a series of mass executions near the municipal stadium and other sites. While estimates of the number killed in Hama vary widely, the most credible reports put the number at between five and ten thousand people.60 58 For more details about the disappeared in Syria, see for example, Radwan Ziadeh, ed., Years of Fear: The Forcibly Disappeared in Syria, http://www.shril-sy.info/enshril/modules/tinycontent/content/Years%20of%20Fear%20- %20English%20Draft.pdf (accessed July 5, 2010); Human Rights Watch, Syria Unmasked, pp. 8-21. 59 For more information on events in Tadmor, see Human Rights Watch, Syria's Tadmor Prison: Dissent Still Hostage to a Legacy of Terror; Human Rights Watch, Syria Unmasked, pp. 15-16; Radwan Ziadeh, Years of Fear, pp. 23-24. 60 For more information about the killings of Hama see Human Rights Watch, Syria Unmasked, pp. 19-21; Syrian Committee for Human Rights, The Massacre of Hama in February 1982: a Genocide and Crime against Humanity, February, 2, 2006, http://www.shrc.org/data/aspx/d5/2535.aspx (accessed June 10, 2010). A Wasted Decade 26

- 31. Table 2. Major Incidents of Human Rights Violations in the early 1980s61 Disappearances in Deir al-Zor on After teenage demonstrators set fire to the local Ba`ath party April 15, 1980 headquarters, police rounded up 38 youths in the eastern city of Deir al-Zor. Though none were charged with a crime, they soon disappeared from the local jail. Parents have never learned their fate. Tadmur Prison, June 27, 1980 When Islamists were blamed for a failed assassination attempt on Hafez al-Asad, government troops entered communal cells at the notorious prison and fired indiscriminately on the prisoners inside. More than a thousand prisoners were killed. Sarmada, July 25, 1980 For reasons that remain unclear, security forces rounded up hundreds of residents from the northern village of Sarmada for interrogation and beating. Some 40 villagers were killed or disappeared. Hama, 1981 After a government checkpoint was attacked outside the city of Hama, soldiers sealed off the city and began house to house searches. Without so much as an identity check, hundreds of men and boys were dragged outside and shot. At least 350 people were killed. Hama Uprising and Repression When government commandos entered Hama to round-up (February 2 to March 5, 1982) opposition members, Islamist fighters resisted, barricading themselves in the old city and killing 100 government and party representatives. The government responded with a fierce bombardment that destroyed much of the city. Troops rounded up and executed hundreds of civilians. In total, between 5,000 and 10,000 people were killed. While many political detainees from the 1980s were released pursuant to various amnesties, some under Hafez al-Asad and others under Bashar, the fate of thousands of disappeared remains unknown, and it is still dangerous to raise these issues inside Syria. Lebanese groups have lobbied hard to shed light on the fate of the disappeared from Lebanon. In May 2005, a joint Lebanese-Syrian committee was finally formed to address the issue. However, five years after beginning its work, it has yet to produce any concrete results or publish any findings. 61 Source of the information is Human Rights Watch, Syria Unmasked, pp. 14-21. 27 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 32. Accordingly, we urge President Bashar al-Asad to: • Set up an independent national commission for truth and justice that includes representatives of the victims’ families, independent civil society activists, and international organizations with experience working on the issue of disappearances such as the ICRC. The commission’s mandate will be to resolve the issue of the missing and the disappeared in Syria, and those abducted from Lebanon and suspected of being detained in Syria. • Support the ratification of the United Nations Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. A Wasted Decade 28

- 33. VI. Annex: List of Political and Human Rights Activists Detained during Bashar al-Asad’s First Decade in Power (This is not an exhaustive list, but rather represents cases that Human Rights Watch was able to document) NAME DATE OF ARREST AND CONTEXT CHARGES/SENTENCE Ma’moun al-Homsi, Detained on August 9, 2001, as part Damascus Criminal Court sentenced him to five years in prison former member of of the crackdown on the Damascus in March 2002 for “an attempt to change the constitution by parliament Spring. He had publicly demanded illegal means, trying to stop the authorities from carrying out democratic changes. their duties mentioned in the law, trying to harm national unity, defaming the state and insulting the legislative, executive and judicial authorities.” Released on January 18, 2006, after serving his sentence. Riad al-Turk, former Detained on September 1, 2001, as SSSC sentenced him on June 26, 2002, to two and a half years head of the part of the crackdown on the for “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means.” unauthorized Damascus Spring. He had stated on He received a presidential pardon and was released on Communist Party Al Jazeera television in August 2001 November 16, 2002, for “humanitarian reasons” related to his (Political Bureau) that “the dictator has died.” bad health. Riad Seif, former Detained on September 6, 2001, as Damascus criminal court sentenced him to five years in April Member of Parliament part of the crackdown on the 2002, for “attempting to change the constitution by illegal Damascus Spring. He was a founder means,” among other charges. Released on January 2006, he of a discussion forum, dubbed the was re-arrested in December 2007 (see Damascus Declaration Forum for National Dialogue. detainees below). Kamal al-Labwani, Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on August 28, 2002, to three years for physician, founder of of the crackdown on the Damascus inciting armed rebellion. He was released on September 9, the Democratic Liberal Spring. He had attended a political 2004, after completing his sentence. He was later re-arrested Gathering seminar in the house of Riad Seif. in November 2005 and is currently serving a 12-year sentence (see box in Section 1 above). Walid al-Bunni, Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on July 31, 2002, to five years for physician, member of of the crackdown on the Damascus “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means.” the Committees for the Spring. He had attended a political Released on January 18, 2006. Revival of Civil Society seminar in the house of Riad Seif. Hassan Sa`dun, Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on August 28, 2002, to two years for involved in the civil of the crackdown on the Damascus “spreading false information.” Released on September 9, forum movement, Spring. 2003, after the end of his sentence. member of the Human Rights Association in Syria Habib `Issa, Lawyer, Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on August 19, 2002, to five years for involved in the civil of the crackdown on the Damascus “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means.” forum movement Spring. He was spokesperson for the Released in January 2006. Jamal al-Attasi Forum for Democratic Dialog and a founding member of Human Rights Society of Syria. Fawaz Tello, engineer Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on August 28, 2003, to five years for of the crackdown on the Damascus “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means.” Spring. Released on January 18, 2006. 29 Human Rights Watch | July 2010

- 34. NAME DATE OF ARREST AND CONTEXT CHARGES/SENTENCE Habib Saleh, key figure Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on June 24, 2002, to three years for of the National of the crackdown on the Damascus “inciting racial and sectarian strife” and other charges. Dialogue Forum, writer, Spring. Released in 2004. He was arrested again in May 2005 and a and political analyst military court sentenced him to three years for “weakening national sentiment” and “spreading false news” for articles critical of the Syrian authorities that he had published on the internet. Released in 2007. He was arrested for a third time on May 7, 2008, and a Damascus criminal court sentenced him on March 15, 2009, to three years in jail for “spreading false information” and “weakening national sentiment” for writing articles criticizing the government and defending opposition figure Riad al-Turk. Aref Dalila, Detained in September 2001 as part SSSC sentenced him on July 31, 2002, to 10 years for economist and of the crackdown on the Damascus “attempting to change the constitution by illegal means.” university professor, Spring. Released on August 7, 2008. founding member of the nongovernmental Committees for the Revival of Civil Society Anwar Asfari, journalist Detained on July 20, 2002, for SSSC sentenced him on June 6, 2005, to five years for holding talks and roundtables in the “belonging to a secret organization with the objective of United Arab Emirates on reform in changing the economic and social status of the state.” Syria. Released on July 21, 2007. Haytham al-Maleh, Charged on October 14, 2002, for Charged with “spreading false news,” “belonging to an human rights lawyer distributing HRAS’s publications and international political association,” and “publishing material and former head of forming a human rights group that caused sectarian friction.” All charges were dropped on Human Rights without governmental approval. July 15, 2003, as part of a presidential amnesty. Detained Association of Syria again on October 14, 2009, for criticizing the continued (HRAS) application of the state of emergency on a TV program. A military court sentenced him on July 3, 2010, to three years for “spreading false news.” He is currently in detention. Hasan Saleh and Detained on December 15, 2002, SSSC sentenced them in February 2004 to three years for Marwan `Uthman, two after they had led a sit-in outside the attempting “to cutoff part of Syrian land to join it to another leaders in the Kurdish Syrian National Assembly calling for country.” Sentence later reduced to 14 months. Yekiti party the removal of the barriers imposed on the Kurdish language. A group of 14 activists All were detained in August 2003 in A military court sentenced 13 of them to three months for known as the “Aleppo Aleppo as they waited to attend a “membership in a secret organization” and sentenced Fateh 14”: Fateh Jamus, talk on the emergency law. Jamus to one year on the same charge. All 14 men were Safwan `Akkash, `Abd released in June 2004. al-Ghani Bakri, Hazim `Ajaj al-Aghra’i, Muhammad Deeb Kor, `Abd al-Jawwad al- Saleh, Hashem al- Hashem, Yaser Qaddur, Zaradesht Muhammad, Rashid Sha`ban, Fuad Bawadqji, Ghazi Mustafa, Najib Dedem, and Samir `Abd al- Karim Nashar A Wasted Decade 30