EXPERIMENT 1 OBSERVATION OF MITOSIS IN A PLANT CELLData Table.docx

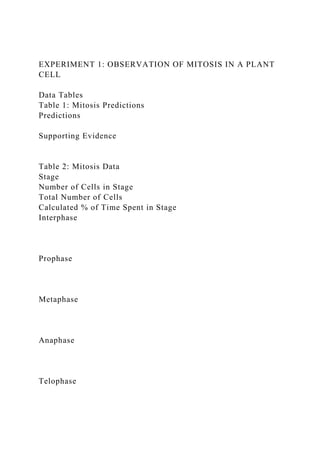

- 1. EXPERIMENT 1: OBSERVATION OF MITOSIS IN A PLANT CELL Data Tables Table 1: Mitosis Predictions Predictions Supporting Evidence Table 2: Mitosis Data Stage Number of Cells in Stage Total Number of Cells Calculated % of Time Spent in Stage Interphase Prophase Metaphase Anaphase Telophase

- 2. Cytokinesis Table 3: Stage DrawingsCell StageDrawing Interphase Prophase Metaphase Anaphase Telophase Cytokinesis Post-Lab Questions 1. Label the arrows in the slide image with the appropriate stage of the cell cycle. A ___________________ B ___________________ C ___________________ D ___________________ E ___________________ F ___________________

- 3. 2. In what stage were most of the onion root tip cells? Does this make sense? 3. As a cell grows, what happens to its surface area-to-volume ratio (hint: think of a balloon being blown up)? How does this ratio change with respect to cell division? 4. What would happen if mitosis were uncontrolled? 5. How accurate were your time predictions for each stage of the cell cycle? 6. Discuss one observation you found interesting while looking at the onion root tip cells. ©eScience Labs, 2016 COUN 506 Journal Article Review Instructions You will write aJournal Article Review, which will be based on your choice of articles from the professional, peer-reviewed journalarticles provided in the Assignment Instructions folder. No outside articles will be accepted. Each Journal Article Review must be approximately 3–5 double-spacedpages (not including the title and reference pages) and must be created in a Microsoft Word document. Use the following guidelines to create your paper: 1. Provide a title page in currentAPA format including only your name, the paper title (referring to the article title), and the institutional affiliation (Liberty University). Keep in mind that current APA recommends that the title length not exceed 12 words. Use the running head in the appropriate place and a page number on every page. Divide your summary into sections with the following Level One headings: Summary, Interaction, and Application (review the current APA Manual for guidance on levels of headings if needed). 2. Develop a summary of the main concepts from the article. Do

- 4. not duplicate the article’s abstract. If the article describes a research study, include brief statements about the hypotheses, methods, results, discussion, and implications. If any test measures or statistical methods used are given in the article, do not provide detailed descriptions of these. Short direct quotations from the article are acceptable, but avoid long quotations in a paper this size. This section is the foundation of your Journal Article Review (at least a third of your paper). Make sure that you include the core points from the article, even if it means a longer section. Do not reference any additional articles in your summary. 3. In your own words, interact (in approximately 1 page) with the article. Appropriate comments for this part of the paper should include, but are not limited to: your initial response to the article, comments regarding the study’s design or methodology (if any), insights you gained from reading the article, your reasons for being interested in this particular article, any other readings that you may plan to do based upon having read the article, and other thoughts you have that might further enhance the discussion of your article. Your subjective comments in this section must be clearly tied to main points from the article, not peripheral ideas. Again, do not reference any other article. 4. In your final section (in approximately 1 page) write how you would apply the information you have learned from this article to a particular counseling situation. This could be in a church or clinical session. Develop this section as if you are a pastor or clinician and your parishioner or client has come to you with a problem—grief, depression, substance abuse, infidelity, etc.— and is needing your help. Adequately describe the counseling scenario, including the presenting problem. Draw out concepts from the article and apply the concepts to the scenario as if you were guided only by the content of the article. Show the reader how you are expressly drawing from the journal article in this

- 5. application section; be sure to cite correctly in current APA format. 5. Provide the complete citation for the article being summarized on a reference page in current APA format. 6. Additionally, consider any other information from previous articles you may have read in previous courses, or in other places you have encountered information relating to the themes in the article you are reviewing. For example, does the ACA Code of Ethics (2014) have anything to say about the themes being discussed in your journal article? Are there passages of Scripture that directly relate to the article? Are there ideas and concepts from previous courses you have taken in your program here at Liberty or elsewhere that relate to the article you have chosen? You are encouraged to include them, and make sure you include proper citations and references at the end of your paper. References: Entwistle, D. N. (2015). Integrative approaches to psychology and Christianity: An introduction to worldview issues, philosophical foundations, and models of integration (3rd ed.). Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN: 9781498223485. Hawkins, R., & Clinton, T. (2015). The new Christian counselor: A fresh biblical & transformational approach. Eugene, OR: Harvest House. ISBN: 9780736943543. McMinn, M. R. (2011). Psychology, theology, and spirituality in Christian counseling (Revised ed.). Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House. ISBN: 9780842352529. Page 1 of 2

- 6. HALL AND FINCHAMSelf–forgiveness SELF–FORGIVENESS: THE STEPCHILD OF FORGIVENESS RESEARCH JULIE H. HALL AND FRANK D. FINCHAM University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Although research on interpersonal forgiveness is burgeoning, there is little con- ceptual or empirical scholarship on self–forgiveness. To stimulate research on this topic, a conceptual analysis of self–forgiveness is offered in which self–forgiveness is defined and distinguished from interpersonal forgiveness and pseudo self–for- giveness. The conditions under which self–forgiveness is appropriate also are iden- tified. A theoretical model describing the processes involved in self–forgiveness following the perpetration of an interpersonal transgression is outlined and the pro- posed emotional, social–cognitive, and offense–related determinants of self–for- giveness are described. The limitations of the model and its implications for future research are explored. In recent years there has been an upsurge of interest in interpersonal for- giveness. Prior to 1985 there were only five studies on forgiveness (Worthington, 1998), a number that since has increased by over 4,000% (PsycINFO, July 2003). However, intrapersonal or self– forgiveness has

- 7. received remarkably little attention in this burgeoning literature. We therefore offer a conceptual analysis of this stepchild of the forgiveness literature, with the goal of stimulating research on the topic. WHAT IS SELF–FORGIVENESS? Few definitions of self–forgiveness can be found in the social sciences lit- erature, but those that do exist emphasize self–love and respect in the face of one’s own wrongdoing. In the philosophy literature, self–for- giveness has been conceptualized as a show of goodwill toward the self while one clears the mind of the self–hatred and self–contempt that re- 621 Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 5, 2005, pp. 621-637 Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Julie Hall, Dept of Psy- chology, Park Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260; E–mail: [email protected] falo.edu sult from hurting another (Horsbrugh, 1974). Similarly, Holmgren (1998) argues that in self–forgiveness, the offender recognizes his/her

- 8. intrinsic worth and its independence from his/her wrongdoing. Philos- ophers posit that self–forgiveness involves a restoration of self– respect (Dillon, 2001; Holmgren, 1998) and consists of three elements (Holmgren, 1998); first, self–forgiveness requires an objective fault or wrongdoing; second, negative feelings triggered by this offense must be overcome; and, third, an internal acceptance of oneself must be achieved. In the psychology literature, self–forgiveness has been defined as “a willingness to abandon self–resentment in the face of one’s own ac- knowledged objective wrong, while fostering compassion, generosity, and love toward oneself” (Enright, 1996, p. 115). Bauer et al. (1992) offer a more abstract definition, considering self–forgiveness as the shift from self–estrangement to a feeling of being at home with the self. Bauer et al. (1992) emphasize that self–forgiveness entails placing the transgression in a larger perspective and realizing that one is merely human. Self–for- giveness also can be conceptualized using a phase model, in which an in- dividual moves through an uncovering phase (e.g., denial, guilt, shame), a decision phase (e.g., change of heart), a work phase (e.g. self–awareness, compassion), and finally an outcome phase (e.g., finding meaning, new purpose; Enright, 1996).

- 9. In the relative absence of a rapprochement between writings on in- terpersonal forgiveness and self–forgiveness, we build upon work on interpersonal forgiveness in offering a conceptual analysis of self–for- giveness that might both integrate writings on forgiveness and guide future research on self–forgiveness. Paralleling McCullough, Worthington, and Rachal’s (1997) definition of interpersonal forgive- ness as a process of replacing relationship–destructive responses with constructive behavior, we conceptualize self–forgiveness as a set of motivational changes whereby one becomes decreasingly motivated to avoid stimuli associated with the offense, decreasingly motivated to retaliate against the self (e.g., punish the self, engage in self– destruc- tive behaviors, etc.), and increasingly motivated to act benevolently to- ward the self. Unlike interpersonal forgiveness, however, in self–for- giveness avoidance is directed toward the victim and/or toward thoughts, feelings, and situations associated with the transgression. This type of avoidance reduces the likelihood that painful thoughts and feelings about the offense will be activated. When self– forgiveness is achieved, such avoidance is unnecessary because the offender is at peace with his or her behavior and its consequences. Retaliation

- 10. and benevolence in both self-forgiveness and interpersonal forgiveness are focused toward the offender. 622 HALL AND FINCHAM The above conception of self–forgiveness is rooted in the tradition of cognitively oriented approaches to motivation initiated by expec- tancy–value theory, later exemplified in Weiner’s attributional theory of motivation (e.g., Weiner, 1986) and currently found in goal theoretic ap- proaches to motivation (e.g., Gollwitzer & Brandstatter, 1997). COMPARING SELF-FORGIVENESS AND INTERPERSONAL FORGIVENESS In addition to similarities at the definitional level, interpersonal and intrapersonal forgiveness share other features. These two forms of for- giveness are both processes that unfold over time and require an objec- tive wrong for which the offender is not entitled to forgiveness but is granted forgiveness nonetheless. Self–forgiveness also parallels inter- personal forgiveness in that it is different from condoning or forgetting a transgression. To forgive oneself is not to say that one’s behavior was ac-

- 11. ceptable or should be overlooked (Downie, 1965). In addition, as with in- terpersonal forgiveness, self–forgiveness is a conscious effort that does not occur unintentionally (Horsbrugh, 1974). Despite these similarities, important distinctions can be drawn be- tween interpersonal and intrapersonal forgiveness and these are sum- marized in Table 1. As mentioned previously, the two forms of forgive- ness differ in the focus of forgiveness–related motivations. In addition, even though interpersonal forgiveness is unconditional, self– forgive- ness need not be (Horsbrugh, 1974). One may set up conditions, such that the self is only forgiven if he or she continues to meet these condi- tions (e.g., “I will forgive myself as long as I continue to make repara- tions to the victim”). Self–forgiveness often entails a resolution to change (Enright, 1996) and to behave differently in the future. Thus, if this resolution is broken, self–destructive motivation may re– emerge and overpower self–constructive motivation. Why is it that such conditions cannot also be applied to interpersonal forgiveness? According to Judaism, forgiveness is contingent upon the offender’s teshuvah, or process of return, which entails specific actions

- 12. on the part of the transgressor (Dorff, 1998; Rye et al., 2000). In contrast, the unconditional view of interpersonal forgiveness is consistent with Christian tradition. Philosophers argue that interpersonal forgiveness is necessarily unconditional, noting that because interpersonal forgive- ness is permanent and cannot be “undone,” the imposition of conditions is inappropriate (Horsbrugh, 1974). Exploration of this debate is beyond the scope of the current paper. Rather, we contend that while interper- s o n a l f o r g i v e n e s s i s m o s t o f t e n v i e w e d a s u n c o n d i t i o n a l , self–forgiveness can easily be conditional or impermanent. SELF–FORGIVENESS 623 Interpersonal forgiveness and self–forgiveness are also distinct in that interpersonal forgiveness does not imply reconciliation with the of- fender whereas reconciliation with the self is necessary in self– forgive- ness (Enright, 1996). As Enright (1996) points out, “Certainly one may mistrust oneself in particular area, but one does not remain alienated from the self” (p. 116). Using this framework, self–forgiveness can be viewed as the vehicle through which self–reconciliation occurs. Thus,

- 13. the consequences of not forgiving the self typically may be more severe than those associated with a lack of interpersonal forgiveness. In inter- personal transgressions, the negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward a transgressor that can occur in the absence of forgiveness may not be activated unless the victim is in contact with the perpetrator. When one harms oneself or someone else, however, the offender must continue to face himself/herself and his/her actions. It is impossible to escape the situation by avoiding the transgressor as one might do in the case of interpersonal transgressions. This fact has led some to suggest that failure to forgive the self may result in self–estrangement or self–de- struction (Horsbrugh, 1974).1 However, to date, there has been no em- pirical work that compares the consequences of self– unforgiveness and interpersonal unforgiveness. As such, this remains a purely theoretical argument. Several other distinctions between intrapersonal and interpersonal forgiveness will be drawn throughout this paper. Beyond the similarities and differences outlined between interper- sonal and intrapersonal forgiveness, how are these processes related temporally? Is one a necessary precondition for the other? It has been suggested that self–forgiveness facilitates interpersonal

- 14. forgiveness by allowing one to identify with one’s offender (Snow, 1993). Similarly, Mills (1995) argues that interpersonal forgiveness is more authentic and meaningful when it follows self–forgiveness. If indeed we cannot for- give others unless we can forgive ourselves, then the role of self–forgive- ness extends far beyond internal, self–focused processes and into the do- main of interpersonal relationships. However, thus far, there is no evidence on the temporal relation between self–forgiveness and inter- personal forgiveness and there is limited evidence on the association be- tween the two constructs, which suggests that they are unrelated or weakly related (e.g., Macaskill, Maltby, & Day, 2002; Mauger et al., 1992; Tangney, Boone, Dearing, & Reinsmith, 2002; Thompson et al., 2005). 624 HALL AND FINCHAM 1. This is not meant to imply that feelings of interpersonal unforgiveness cannot be chronically activated and therefore occur in the absence of relevant external stimuli. Simi- larly, we do not discount the possibility that failure to forgive another can sometimes have severe consequences. Rather, our description focuses on prototypic cases.

- 15. FORGIVING THE INJURY TO THE SELF OR THE INJURY TO THE OTHER? Whereas interpersonal forgiveness focuses upon harm to the victim that results from the behavior of a transgressor, there are two possible foci of self–forgiveness (Horsbrugh, 1974). One may try to forgive the self for a self–imposed injury or, alternatively, for an injury to another person. Most commonly, these two factors are interrelated, as the reality of harming another person also inflicts hurt upon the self. Given these two forms of hurt, which is the target of self–forgiveness? Horsbrugh (1974) has argued that one can forgive the self only for the hurt one has brought to another person. The self–imposed hurt is real, but it is not the target of self–forgiveness. Rarely does one say, “I am sorry that I hurt myself”—it is more common to regret the actions that led to the self– imposed hurt (e.g., “I can’t believe I did X”). This position rests on the view that actions are not the proper target of forgiveness. Instead, forgiveness focuses on the hurt resulting from actions, as, without the consequential hurt, it is argued that there would be little or nothing to forgive. For example, one may be unfaithful to one’s romantic partner, but the partner’s forgive-

- 16. ness is relevant only if the infidelity violated the norms of that relation- ship and hurt one’s partner. Under different conditions, such as an open relationship, the same actions would not require forgiveness because they would not result in hurt. This position can be challenged because of SELF–FORGIVENESS 625 TABLE 1. Distinctions between Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Forgiveness Intrapersonal or Self–forgiveness Interpersonal Forgiveness Form of objective wrongdoing Behaviors, thoughts, desires, feelings Behaviors Focus of forgiveness Harm to self or to another Harm to victim Empathy Inhibits forgiveness Facilitates forgiveness Limits Conditional or unconditional Unconditional Reconciliation with victim Required Not required

- 17. Focus of avoidance Transgression–related stimuli (e.g., victim, situations, thoughts, etc.) Offender Focus of revenge Offender (i.e., self) Offender (i.e., other) Focus of benevolence Offender (i.e., self) Offender (i.e., other) Consequences of unforgiveness Extreme Moderate its failure to accommodate abrogation of the moral order (failure to be- have in a way that one ought to behave), which is considered to be wrong even in the absence of hurt and therefore still might be the proper target of forgiveness. An additional problem is that the above conceptualization of self–for- giveness neglects an entire domain in which self–forgiveness may be rel- evant. Although transgressions in which the offender and victim are the same do not meet its criteria, these offenses are nevertheless painful. Thus, we argue that self–forgiveness also can apply to situations in which the only victim of one’s behavior is the self. There are innumera-

- 18. ble situations in which we inflict harm on ourselves (“let ourselves down”) and these range from academic failures (e.g., failing a test be- cause of lack of preparation) to social failures (e.g., failing to be appro- priately assertive). Although loved ones also may be affected by these behaviors, the primary victim is oneself. How do we forgive ourselves for such actions? This domain of self–forgiveness may be especially rele- vant to certain clinical populations, such as substance abusers or indi- viduals with eating disorders. These individuals may suffer from guilt and/or shame because of their inability to stop engaging in self– destruc- tive behavior. However, it is important to recognize that injuries to the self can occur without any overt, behavioral wrongdoing. The self also can be injured by wrongful thoughts, feelings, or desires (Dillon, 2001). Dillon (2001) provides examples of behaviors that might require self–forgiveness, such as racist thoughts or fears, wishes for the death of a sick parent, or sexual excitement over violence. Finally, we can distinguish forgiving the self for the hurt that results from a particular act from forgiving the self for the hurt that results from recognizing any character flaw underlying the act (for “being the type of person who acts like this”). It is hypothesized that linking the

- 19. act to a character flaw is more likely to the extent that there is a history of similar behavior and that self–forgiveness is correspondingly harder to achieve under these conditions. TRUE SELF–FORGIVENESS VERSUS PSEUDO SELF– FORGIVENESS In order to truly forgive oneself, one must either explicitly or implicitly ac- knowledge that one’s behavior was wrong and accept responsibility or blame for such behavior (Dillon, 2001; Holmgren, 1998). Without these el- ements, self–forgiveness is irrelevant and pseudo self– forgiveness be- comes likely. Pseudo self–forgiveness occurs when an offender fails to acknowledge wrongdoing and accept responsibility. In such a situation, one may indicate that one has forgiven oneself when, in fact, one does not believe one did anything wrong. The realization of wrongdoing and ac- 626 HALL AND FINCHAM ceptance of responsibility generally initiate feelings of guilt and regret, which must be fully experienced before one can move toward self–for- giveness. Attempts to forgive oneself without cognitively and

- 20. emotion- ally processing the transgression and its consequences are likely to lead to denial, suppression, or pseudo self-forgiveness. Thus, our definition of self–forgiveness as motivational change rests on the assumption that the offender both acknowledges wrongdoing and accepts responsibility. Without this assumption, there can be no motivational change, as the of- fender already is motivated to act benevolently toward the self. However, this distinction rarely is made in the empirical literature. Self– forgiveness often is studied using a narrative method in which individuals recall situ- ations whereby they forgave themselves or did not forgive themselves. However, it is unclear whether this method measures true forgiveness or pseudo–forgiveness. It is not made explicit that forgiving individuals also accept responsibility and wrongdoing and that they fully realize the con- sequences of their actions. This problem is exacerbated when self–for- giveness is assessed using rating scales as responses to items in such scales appear not to distinguish genuine forgiveness from pseudo–for- giveness (e.g., “I hold grudges against myself for negative things I’ve done,” Thompson et al., 2005; “I find it hard to forgive myself for some things I have done,” Mauger et al., 1992). Perhaps not

- 21. surprisingly, there is some evidence that self–forgiveness is positively related to narcissism and self–centeredness and negatively related to moral emotions such as guilt and shame (e.g., Tangney et al., 2002). Forgiveness requires a great deal of inner strength, and thus pseudo–for- giveness may be an appealing alternative that (on the surface) has the same benefits as true self–forgiveness. The offender is absolved of guilt and is able to feel and act benevolently toward the self. However, while pseudo–forgiveness and true forgiveness may appear to have the same re- sults, they are drastically different. True self–forgiveness is often a long and arduous process that requires much self–examination and may be very un- comfortable. In contrast, pseudo self–forgiveness may be achieved by self–deception and/or rationalization, in which the offender fails to “own up” to his/her behavior and its consequences (Holmgren, 2002). Given these differences, are the end results of true forgiveness and pseudo–for- giveness really indistinguishable? There is little data to answer this ques- tion, but it is doubtful that pseudo–forgiveness yields the same emotional, psychological, and physical benefits as true self–forgiveness. IS SELF–FORGIVENESS ALWAYS APPROPRIATE?

- 22. What of situations in which an individual perceives he/she is responsi- ble and feels guilty about an event but is not actually at fault? This is of- SELF–FORGIVENESS 627 ten the case with traumatic events, such as the suicide of a loved one. Survivors may blame themselves and feel guilty when they are not re- sponsible for the event. Is self–forgiveness pertinent in these situations? The answer arguably is yes, but only under certain conditions. If a per- son is adamant in the belief that he or she is responsible for an event, self–forgiveness would only be appropriate provided bona fide at- tempts first had been made to examine the evidence, to identify the per- son’s wrongful behavior, and to determine accurately the degree of responsibility the individual should accept for the event. In some cases (e.g., being the victim of a rape), the person may mislabel a normal be- havior as wrongful (e.g., “I should not have worn that dress") or accept responsibility even in the absence of any wrongful behavior (e.g., “I should not have walked home”). In the absence of wrongful behavior

- 23. there is nothing to forgive. There are two other common concerns that must be addressed when considering the appropriateness of self–forgiveness. The first is whether self–forgiveness is justified when an individual has committed a truly heinous offense, such as rape or murder. This is a controversial topic. Scholars have debated whether victims of such transgressions should forgive their attackers (e.g., Murphy, 2002), and this debate extends to self–forgiveness. The issue at the core of this controversy actually may be the distinction between pseudo self–forgiveness and true self– for- giveness. Few things are more offensive than observing a criminal who seemingly has no remorse for his/her actions. However, it is unlikely that this individual has achieved true self–forgiveness. It is far more likely that he/she is engaging in pseudo–forgiveness. It is probably rare that criminals are able to reach true self–forgiveness, as the processes in- volved may be too painful and difficult. But for an offender who admits to behaving in an unspeakable manner and who is genuinely pained by his/her behavior and its consequences, self–forgiveness is less contro- versial. Holmgren (2002) takes a similar stance, arguing that genuine

- 24. self–forgiveness is always appropriate. This is admittedly a sensitive issue, and there is no easy answer. A second frequent concern related to self–forgiveness is that it is a sign of disrespect toward the victim, and thus is only appropriate after the of- fender is granted forgiveness by the victim. However, self– forgiveness is only disrespectful to the victim when it takes the form of pseudo–for- giveness, in which case the offender does not appreciate the gravity of his or her actions and their consequences. When an offender acknowl- edges and accepts responsibility for wrongdoing and is willing to apolo- gize or make restitution to the victim, self–forgiveness is not a sign of disrespect (Holmgren, 1998). Thus, receiving forgiveness from the vic- tim is not required for self–forgiveness to be appropriate. 628 HALL AND FINCHAM DISPOSITIONAL OR OFFENSE–SPECIFIC? Self–forgiveness need not apply only to specific transgressions through which one has harmed oneself or another person, it also can be consid- ered across time and a range of transgressions, as a personality trait.

- 25. Trait self–forgiveness is positively associated with self–esteem and life satisfaction and negatively associated with neuroticism, depression, anxiety, and hostility (Coates, 1997; Maltby, Macaskill, & Day, 2001; Mauger et al., 1992). It is weakly related, and in some studies unrelated, to forgiveness of others (Macaskill et al., 2002; Tangney et al., 2002; Thompson et al., 2003). Although self–forgiveness across time and trans- gressions is an important dispositional construct, it is also critical to ex- amine how self–forgiveness may vary from offense to offense and to consider the emotional, social–cognitive, and offense–related factors that may facilitate self–forgiveness following a specific transgression. TOWARD A MODEL OF SELF–FORGIVENESS Having drawn several relevant conceptual distinctions, we are now in a position to offer an initial model of self–forgiveness. In turning to this task, we immediately face a choice, as the processes involved in self–for- giveness are likely to differ according to whether the focus is upon inter- personal or intrapersonal transgressions. We doubt that self- forgiveness related to both types of transgressions can be captured adequately in a single model and therefore focus our efforts on only one, self–

- 26. forgive- ness of interpersonal transgressions. We posit that the motivational changes that define self–forgiveness are driven by cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes, which are laid out in our model. These pro- cesses are the means to an end; namely, motivational change that consti- tutes self–forgiveness. Figure 1 depicts our model of self– forgiveness. We first describe the components of the model before outlining its implications for future research. EMOTIONAL DETERMINANTS OF SELF–FORGIVENESS Guilt. Given the long history of the concept of guilt in the psychologi- cal literature, it is surprising that the relation between guilt and self–for- giveness has received relatively little attention (for an exception, see Tangney et al., 2002). Guilt can be assessed as a trait or a state, and it in- volves tension, remorse, and regret resulting from one’s actions (Tangney, 1995a). Guilt is “other–oriented” in that it focuses on one’s ef- fect on others. Guilt fosters other–oriented empathic concern and moti- vates the offender to exhibit conciliatory behavior toward the victim, SELF–FORGIVENESS 629

- 28. o rg iv en es s. such as apologizing, making restitution, or seeking forgiveness (Ausubel, 1955; Tangney, 1995b). However, while there likely is a posi- tive association between conciliatory behaviors and self– forgiveness, the other–oriented empathy fostered by guilt actually may inhibit self–forgiveness. Zechmeister and Romero (2002) found that, compared to individuals who had not forgiven themselves for an offense, those who had reached self–forgiveness were less likely to report guilt and other–focused empathy. Thus, while there appears to be a negative asso- ciation between guilt and self–forgiveness, this association likely is mediated by conciliatory behavior and empathic processes. Shame. Unlike guilt, which involves a focus on one’s behavior, shame is associated with a focus on the self (Lewis, 1971; Tangney, 1995a). Lewis’s (1971) observations are useful for illustrating this distinction:

- 29. “The experience of shame is directly about the self, which is the focus of evaluation. In guilt, the self is not the central object of negative evalua- tion, but rather the thing done or undone is the focus. In guilt, the self is negatively evaluated in connection with something but is not itself the focus of the experience.” (p. 30) As with guilt, there likely is a negative association between shame and self–forgiveness. However, whereas guilt may promote conciliatory be- havior toward one’s victim, shame is more likely to promote the self–de- structive intentions associated with failure to forgive the self because the offender may view the offense as a reflection of his or her self– worth. Shame often motivates an avoidance response that is consistent with a lack of self–forgiveness (Tangney, 1995a). Thus, the negative association between shame and self–forgiveness is expected to be stronger than the relation between guilt and self–forgiveness. SOCIAL–COGNITIVE DETERMINANTS OF SELF– FORGIVENESS Attributions. Research on interpersonal forgiveness has shown that benign attributions for an offender’s behavior are associated with more

- 30. forgiveness, while maladaptive attributions are associated with less for- giveness (Boon & Sulsky, 1997; Bradfield & Aquino, 1999; Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Fincham, Paleari, & Regalia, 2002; Weiner, Graham, Pe- ter, & Zmuidinas, 1991). This link between attributions and interper- sonal forgiveness may generalize to self–forgiveness. Zechmeister and Romero (2002) found that offenders who had not forgiven themselves were more likely to maladaptively attribute their behavior to arbitrary or senseless motives than self–forgiving offenders. Also, self– forgiving individuals were more likely to adaptively attribute some of the blame SELF–FORGIVENESS 631 to the victim. Given the tendency to attribute one’s own behavior to ex- ternal forces and attribute other’s behavior to internal forces (i.e., the ac- tor–observer effect; Jones & Nisbett, 1972), this process actually may en- hance self–forgiveness. Thus, as with interpersonal forgiveness, external, unstable, and specific attributions for one’s own behavior may facilitate self–forgiveness, while internal, stable, and global attributions may make self–forgiveness more difficult. Weiner (1986, 1995) argues

- 31. that causal attributions give rise to emotional reactions (e.g., guilt), which then influence the offender’s behavior. For example, an offender who maladaptively attributes his/her own behavior may feel excessive guilt and be more likely to then seek forgiveness. OFFENSE–RELATED DETERMINANTS OF SELF– FORGIVENESS Conciliatory Behavior. The extent to which an offender apologizes and seeks forgiveness for a transgression is positively associated with the victim’s level of interpersonal forgiveness (e.g., Darby & Schenkler, 1982; McCullough et al., 1997; McCullough et al., 1998; Weiner et al., 1991). Seeking forgiveness from the victim of a transgression or from a Higher power also may play an important role in the offender’s self–for- giveness. Offenders may be indirectly motivated to seek forgiveness by their attributions for their own behavior or the severity of the offense (Sandage, Worthington, Hight, & Berry, 2000) or directly motivated by guilt (Ausubel, 1955; Tangney, 1995b). Apologies and other conciliatory behaviors toward the victim may serve the function of easing the of- fender’s guilt about the transgression. Goffman (1971) posits: “An apology (and hence also a confession) is a gesture through

- 32. which the individual splits himself into two parts, the part that is guilty of an offense and the part that dissociates itself from the deceit and affirms a belief in the offended rule” (as cited in Gold & Weiner, 2000, p. 292). This idea is empirically supported by Zechmeister and Romero (2002), who found that self–forgiving offenders were more likely to report apol- ogizing and making amends to the victim than were offenders who did not forgive themselves. Similarly, Witvliet, Ludwig, and Bauer (2002) showed that when offenders imagined seeking forgiveness from some- one they had wronged, their perceptions of self–forgiveness increased and their basic and moral emotions improved. Thus, conciliatory behav- iors toward one’s victim may promote self–forgiveness by absolving an offender of his or her guilt. Perceived Forgiveness from Victim or Higher Power. A r e l a t e d f a c t o r that may influence self–forgiveness is the extent to which an offender be- 632 HALL AND FINCHAM lieves he/she is forgiven by the victim or by a Higher power.

- 33. Witvliet et al. (2002) found that imagining a victim’s merciful response to one’s for- giveness–seeking efforts resulted in physiological responses consistent with increases in positive emotion and decreases in negative emotion. Further, imagining seeking forgiveness and merciful responses from victims resulted in greater perceived interpersonal forgiveness among offenders. Thus, actual apologies and conciliatory behavior toward a victim also may increase a transgressor’s sense of being forgiven by the victim, thereby reducing guilt. However, Zechmeister and Romero (2002) compared self–forgiving offenders with offenders who were not able to forgive themselves and found no difference in reports of being forgiven by the victims. In light of these contradictory findings, the rela- tion between forgiveness by the victim and the offender’s self– forgive- ness requires further clarification. It is also important to consider the role of forgiveness from a Higher power. There is preliminary evidence to suggest that perceived forgiveness from God is positively associated with self–forgiveness. Cafaro and Exline (2003) asked individuals to fo- cus on an incident in which they had offended God and found that self–forgiveness was positively correlated with believing that

- 34. God had forgiven the self for the transgression. Thus, we predict that perceived forgiveness from both the victim and a Higher power will be positively associated with self–forgiveness. Severity of the Offense. The association between a transgression’s se- verity and interpersonal forgiveness is among the most robust relations in the forgiveness literature. More severe (hurtful) transgressions are as- sociated with less forgiveness (Boon & Sulsky, 1997; Darby & Schenkler, 1982; Girard & Mullet, 1997). The severity of an offense, in terms of its consequences, also may predict an offender’s degree of self– forgiveness. Although self–forgiveness requires an acknowledged wrongdoing that negatively affects another person, it is possible that an offender also may realize some positive consequences of the transgression. For example, the offender may feel that he or she has grown from the event or that his or her post–offense relationship with the victim is stronger. Offenders who have forgiven themselves report more positive consequences and fewer lasting negative consequences of the transgression than do of- fenders who have not forgiven themselves (Zechmeister & Romero, 2002). Thus, it is predicted that more severe transgressions will

- 35. be associated with lower levels of self–forgiveness. LIMITATIONS OF THE MODEL It is important to note that this model is not intended to be a comprehen- sive model of self–forgiveness. There are undoubtedly other factors that SELF–FORGIVENESS 633 may facilitate self–forgiveness, such as relationship-level factors (e.g., was the victim a loved one or a stranger?) and personality-level factors (e.g., neuroticism). However, in light of research on interpersonal for- giveness (McCullough et al., 1998), it is expected that these variables are more distally related to self–forgiveness than the determinants dis- cussed here. The proposed model also is limited in that there is as yet no evidence that supports causal relationships among these variables. IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH Notwithstanding the limitations noted, the model outlined has several implications for future research. Chief among these is that it has the po- tential to inform self–forgiveness interventions, which have

- 36. prolifer- ated in the popular literature (e.g., Rutledge, 1997). To date, however, there are no empirically validated interventions designed specifically to facilitate self–forgiveness, although several have been effective in promoting interpersonal forgiveness (see Worthington, Sandage, & Berry, 2000). This is a much needed area of development in the forgive- ness literature, as being unable to forgive oneself is associated with lower self–esteem and life satisfaction and higher neuroticism, depres- sion, anxiety, and hostility (Coates, 1997; Maltby et al., 2001; Mauger et al., 1992). Given the deleterious effects of self–unforgiveness, why have no interventions been developed to target these processes? This gap in the forgiveness literature is most likely due to the fact that very little is known about factors that may influence self– forgiveness. Thus, the proposed model has the potential to aid in the development of self–forgiveness interventions, as targeting factors such as attributions and guilt or increasing conciliatory behavior toward the victim may increase self–forgiveness. However, in order to conduct such an intervention and evaluate its ef- fects, one must have a reliable method of measuring self–

- 37. forgiveness. Although there are a few instruments to assess dispositional self–for- giveness (Mauger et al., 1992; Thompson et al., 2003), there are no pub- lished measures for self–forgiveness for a specific transgression (see Wahkinney, 2002, for an unpublished measure). Thus, the definition and model of self–forgiveness proposed here provide a foundation for the development of a measure of offense–specific self– forgiveness. Such a measure would be not only important in assessing the effects of for- giveness interventions but also critical to the future of self– forgiveness research. As mentioned, much of the literature on self– forgiveness as- sesses the construct dichotomously (forgave versus didn’t forgive), which is incompatible with the view of self–forgiveness as a process with many levels. A measure of self–forgiveness that assesses the extent 634 HALL AND FINCHAM SELF–FORGIVENESS 635 of constructive and destructive motivations will enable researchers to differentiate complete lack of self–forgiveness from partial self–forgive-

- 38. ness or total self–forgiveness. Such a measure also will aid in assessing self–forgiveness from many different perspectives, initially through cross–sectional and/or retrospective research and ultimately in experimental or longitudinal studies. The current paper is offered as a framework from which such a measure could be developed. Although this paper is intended to stimulate interest and research on self–forgiveness, it is critical that this research be founded on a solid the- oretical base and that this foundation be established before a literature on self–forgiveness begins to take shape. Thus, the most pressing issue for future self–forgiveness research is the empirical validation of a theo- retical model such as the one proposed here. It will be essential to evalu- ate how well this model fits actual data regarding the self– forgiveness of interpersonal transgressions. It also will be important to determine whether specific determinants are associated with constructive (i.e. be- nevolence) and/or destructive (i.e., avoidance, retaliation) aspects of self–forgiveness. Once such a model is established, more specific hypotheses about the nature and course of self–forgiveness can be explored. CONCLUSION

- 39. Self–forgiveness has been overshadowed by research on interpersonal forgiveness and, as a consequence, has received little attention in the for- giveness literature. We believe that this dearth of research is the result of oversight and limited understanding of self–forgiveness and that it does not reflect the unimportance of self–forgiveness or a lack of interest in the topic. The present paper is intended to stimulate research on the topic by offering a much needed theoretical model of self– forgiveness of interpersonal transgressions. The value of the model lies not only in the extent to which it receives empirical support but also in its ability to facilitate research on self–forgiveness. REFERENCES Ausubel, D.P. (1955). Relationships between shame and guilt in the socializing process. Psychological Review, 62, 378–390. Bauer, L., Duffy, J., Fountain, E., Halling, S., Holzer, M., Jones, E., et al. (1992). Exploring self–forgiveness. Journal of Religion and Health, 31(2), 149– 160. Boon, S. & Sulsky, L. (1997). Attributions of blame and forgiveness in romantic relation-

- 40. ships: A policy–capturing study. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12(1), 19–45. Bradfield, M. & Aquino, K. (1999). The effects of blame attributions and offender likeable- ness on forgiveness and revenge in the workplace. Journal of Management, 25(5), 607. Cafaro, A. M. & Exline, J. J. (2003, March). Correlates of self– forgiveness after offending God. Poster presented at the first annual Mid–winter Research Conference on Religion and Spirituality, Timonium, MD. Coates, D. (1997). The correlations of forgiveness of self, forgiveness of others, and hostility, de- pression, anxiety, self–esteem, life adaptation, and religiosity among female victims of domestic abuse. Dissertation Abstracts International, 58(05), 2667B. (UMI 9734479). Darby, B.W. & Schlenker, B.R. (1982). Children’s reactions to apologies. Journal of Personal- ity and Social Psychology, 43, 742–753. Dillon, R.S. (2001). Self–forgiveness and self–respect. Ethics, 112, 53–83. Dorff, E.N. (1998). The elements of forgiveness: A Jewish approach. In E.L. Worthington (Ed.), Dimensions of forgiveness (pp. 321–339). Philadelphia: Templeton Press. Downie, R.S. (1965). Forgiveness. Philosophical Quarterly, 15, 128–134. Enright, R.D. (1996). Counseling within the forgiveness triad:

- 41. On forgiving, receiving for- giveness, and self–forgiveness. Counseling & Values, 40(2), 107–127. Fincham, F., Paleari, F., & Regalia, C. (2002). Forgiveness in marriage: The role of relation- ship quality, attributions, and empathy. Personal Relationships, 9, 27–37. Girard, M. & Mullet, E. (1997). Forgiveness in adolescents, young, middle–aged, and older adults. Journal of Adult Development, 4(4), 209–220. Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. New York: Basic. Gold, G.J. & Weiner, B. (2000). Remorse, confession, group identity, and expectancies about repeating a transgression. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22(4), 291–300. Gollwitzer P.M. & Brandstatter, V. (1997). Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. Journal of Personaliy and Social Psychology, 73, 186– 99. Holmgren, M.R. (1998). Self–forgiveness and responsible moral agency. The Journal of Value Inquiry, 32, 75–91. Holmgren, M.R. (2002). Forgiveness and self–forgiveness in psychotherapy. In S. Lamb & J.G. Murphy (Eds.), Before forgiving: Cautionary views of forgiveness in psychotherapy (pp. 112–135). New York: Oxford University Press.

- 42. Horsbrugh, H.J. (1974). Forgiveness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 4(2), 269–282. Jones, E.E. & Nisbett, R.E. (1972). The actor and the observer: Divergent perception of the causes of behavior. In E. Jones, D. Kanouse, H. Kelley, R. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attributions: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 79–94). Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press. Lewis, H.B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press. Macaskill, A., Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2002). Forgiveness of self and others and emotional em- pathy. Journal of Social Psychology, 142(5), 663–665. Maltby, J., Macaskill, A., & Day, L. (2001). Failure to forgive self and others: A replication and extension of the relationship between forgiveness, personality, social desirabil- ity, and general health. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 881–885. 636 HALL AND FINCHAM Mauger, P.A., Perry, J.E., Freeman, T., Grove, D.C., McBride, A.G., & McKinney, K.E. (1992). The measurement of forgiveness: Preliminary research. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 11(2), 170–180. McCullough, M., Rachal, K., Sandage, S., Worthington, E.,

- 43. Brown, S., & Hight, T. (1998). In- terpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and mea- surement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1586–1603. McCullough, M., Worthington, E., & Rachal, K. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close re- lationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 321–336. Mills, J.K. (1995). On self–forgiveness and moral self– representation. Journal of Value In- quiry, 29, 407–409. Murphy, J.G. (2002). Forgiveness in counseling: A philosophical perspective. In S. Lamb & J.G. Murphy (Eds.), Before forgiving: Cautionary views of forgiveness in psychotherapy (pp. 41–53). New York: Oxford University Press. Rutledge, T. (1997). The self-forgiveness handbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. Rye, M.S., Pargament, K.I., Ali, M.A., Beck, G.L., Dorff, E.N., Hallisey, C., et al. (2000). Religious perspectives on forgiveness. In M. McCullough, K.I. Pargament, & C.E. Thoresen (Eds.) Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp.17–40). NY: Guilford Press. Sandage, S.J., Worthington, E.L., Hight, T.L., & Berry, J.W. (2000). Seeking forgiveness: Theoretical context and an initial empirical study. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 28(1), 21–35.

- 44. Snow, N.E. (1993). Self–forgiveness. The Journal of Value Inquiry, 27, 75–80. Tangney, J.P. (1995a). Recent advances in the empirical study of shame and guilt. American Behavioral Scientist, 38(8), 1132–1145. Tangney, J.P. (1995b). Shame and guilt in interpersonal relationships. In J. P. Tangney & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self–conscious emotions: Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 114–139). New York: Guilford Press. Tangney, J., Boone, A.L., Dearing, R. & Reinsmith, C. (2002). Individual differences in the pro- pensity to forgive: measurement and Implications for Psychological and Social Adjustment. Manuscript submitted for publication. Thompson, L.Y., Snyder, C.R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S.T., Rasmussen, H.N., Billings, L.S., et al. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Per- sonality, 73(2), 313–359. Wahkinney, R.L. (2002). Self–forgiveness scale: A validation study. Dissertation Abstracts International, 62(10), 3296A. (UMI 3029616 ). Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer–Verlag. Weiner, B. (1995). Judgments of responsibility. New York: Guilford Press.

- 45. Weiner, B., Graham, S., Peter, O., & Zmuidinas, M. (1991). Public confession and forgive- ness. Journal of Personality, 59(2), 281–312. Witvliet, C.V., Ludwig, T.E., & Bauer, D.J. (2002). Please forgive me: Transgressors’ emo- tions and physiology during imagery of seeking forgiveness and victim responses. Journal of Psychology & Christianity, 21(3), 219–233. Worthington, E.L. (1998). Introduction. In E. L. Worthington (Ed.), Dimensions of forgive- ness: Psychological research and theological perspectives (pp. 1–5). Philadelphia: Templeton Press. Worthington, E.L., Sandage, S.J., & Berry, J.W. (2000). Group interventions to promote for- giveness. In M.E. McCullough, K. Pargament, & C. Thoreson (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 228–253). New York: Guilford Press. Zechmeister, J.S., & Romero, C. (2002). Victim and offender accounts of interpersonal con- flict: Autobiographical narratives of forgiveness and unforgiveness. Journal of Per- sonality and Social Psychology, 82(4), 675–686. SELF–FORGIVENESS 637

- 46. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHRISTIAN CLIENTS' PREFERENCES REGARDING PRAYER AS A COUNSELING INTERVENTION Weld, Chet, EDD;Eriksen, Karen, PHD Journal of Psychology and Theology; Winter 2007; 35, 4; ProQuest pg. 328 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

- 47. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

- 48. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Therapists' Integration of Religion and Spirituality in Counseiing: A Meta-Analysis Donald F. Walker, Richard L. Gorsuch, and Siang-Yang Tan The authors conducted a 26-study meta-analysis of 5,759 therapists and their integration of religion and spirifuaiity in counseiing. Most therapists consider spirituaiity relevant to their iives but rareiy engage in spirituai practices or participate in organized religion. Marriage and famiiy thera- pists consider spirituaiity more reievant and participate in organized religion to a greater degree than therapists from other professions. Across professions, most therapists surveyed (over 80%) rareiy discuss spirituai or reiigious issues in training, in mixed sampies of reiigious and secular thera- pists, therapists' reiigious faith was associated with using religious and spiritual techniques in counseiing frequently, willingness to discuss reli- gion in therapy, and theoretical orientation. Therapists' integration of religion and spirituality in counseling

- 49. has beenevaluated in 26 studies of 5,759 psychotherapists from the fieldsof clinical and counseling psychology, psychiatry, social work, and pas- toral counseling. We suggest that it is now appropriate to perform a meta- analysis of the existing research. We discuss the relevance of religion and spirituality to counseling, review methods of integrating religion and spiri- tuality in coimseling, and conduct a meta-analysis of studies concerning thera- pists' integration of religion and spirituality into counseling. Relevance of Religion and Spirituality to Counseling In the area of multicultural theory, psychologists have continued to call for psychological treatments and interventions that are culturally sensitive and relevant and that integrate aspects of client culture into the counseling pro- cess (D. W. Sue & Sue, 1999; S. Sue, 1999). In addition, psychologists have increasingly recognized that religion and spirituality are relevant aspects of client diversity that psychologists should be able to recognize while treat- ing religious or spiritual clients with sensitivity (Ridley, Baker, & Hill, 2001; D. W. Sue, Bingham, Porche-Burke, & Vasquez, 1999). Richards and Bergin (2000) have proposed that the integration of religious and spiritual culture in counseling is conceptually similar to the dynamics of more general multicultural counseling attitudes and skills

- 50. previously advanced by other multicultural researchers (e.g., D. W. Sue & Sue, 1999). Richards and Bergin (2000) further suggested that multicultural competent attitudes and skills regarding religion and spirituality encompass several domains. Donald F. Walker, Richard L. Gorsuch, and Siang-Yang Tan, Graduate School of Psychology, Fuller Theological Seminary. A portion of this research was presented at the 2001 annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Donald F. Walker, Fuller Theological Seminary, Graduate School of Psy- chology, 180 N. Oakland Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91101 (e-mail: [email protected]). Counseiing and Vaiues • October 2004 • Voiume 49 69 Among the domains of multicultiaral attitudes and skills most pertinent to this study are (a) an awareness of one's own cultural heritage, (b) respect and comfort with other cultures and values that differ from one's own, and (c) an awareness of one's helping style and how this style could affect clients from other cultural back- grounds. Hence, knowledge of religion and spirituality is an important element of therapists' multicviltural competency. Religion and spirituality are important aspects of multicultural competency for

- 51. therapists to consider given the religious culture in America. Researchers have found that more than 90% of Americans claim either a Protestant or Catholic religious affiliation (Keller, 2000), 40% of Americans attend religious services on a weekly basis, and more than two thirds of Americans consider personal spiritual prac- tices to be an important part of their daily lives (Hoge, 1996). Thus, it is important for counselors to understand how their own religious and spiritual culture may differ from that of the general populace and the clients whom they serve. This meta-analysis has several aims. One purpose of this study was to examine via meta-analysis the spiritual and religious culture and values of counselors. We use this information to suggest ways in which therapists' religious cultures may differ from those of their clients and to explore how such differences might be con- structively approached in counseling. A second purpose of this study was to ex- plore via meta-analysis links between the personal religiousness of counselors and therapists and several counseling-related variables. We use this information to understand across studies how therapists' religiousness relates to their helping style with clients from varying religious and spiritual backgrounds. Methods of Integrating Religion and Spirituality in Counseling

- 52. One issue that has been problematic when discussing methods of integrating reli- gion and spirituality in counseling has been agreeing on exactly what is being inte- grated. Pargament (1999), for example, noted that psychologists of religion rarely agree on specific definitions of religion and spirituality. However, on a broad level, religion has typically been defined as that which is more organizational, ritual, and ideologi- cal, whereas spirituality has typically been defined as that which is more personal, affective, and experiential (Pargament, 1999; Richards & Bergin, 1997). In this study, the same broad definitions will be used when referring to religion and spirituality. Therapists have proposed several different methods of integrating religious and spiritual culture into counseling. According to Tan (1996), explicit integration refers to a more overt approach that directly and systematically deals with spiritual or religious issues in therapy, and uses spiritual resources like prayer, Scripture or sacred texts, referrals to church or other religious groups or lay counselors, and other religious practices, (p. 368) Tan noted that this approach to coimseling emphasizes both therapist and cli- ent spirituality and integrates counseling with some form of spiritual direction. Another approach to integrating religion and spirituality in

- 53. counseling is the implicit integration of religion or spirituality. Implicit integration is "a more covert approach that does not initiate the discussion of religious or spiritual is- 70 Counseling and Values • October 2004 • Volume 49 sues and does not openly, directly, or systematically use spiritual resources like prayer and Scripture or other sacred texts, in therapy" (Tan, 1996, p. 368). An ex- ample of implicit integration is basing therapeutic values on theistic principles from an organized religion. Implicit integration maybe the preferred mode of integra- tion for therapists who profess a religious faith or engage in spiritual practices but who are not trained in the explicit integration of religion and spirituality. Shafranske (1996) conducted a review of training in explicit and implicit inte- gration. His review suggested that "education and training within the area of psy- chology and religion appears to be very limited" (p. 160) and that the majority of therapists never discuss religious or spiritual issues in their clinical training. Richards and Bergin (1997) noted that such therapists run the risk of practicing outside the boundaries of professional competence or imposing their own values on religious or spiritual clients. Shafranske (1996) suggested that most

- 54. therapists' approach to the integration of religion and spirituality in psychotherapy was not based on graduate trairung in the area but centered primarily on the personal religious and spiritual experience of the therapist. A third form of integration is intrapersonal integration, which refers to the manner in which a therapist uses his or her personal religious or spiritual experience in counseling (Tan, 1987). An example of intrapersonal integration is silently pray- ing for a client during counseling. This study attempts to determine how therapists practice their religion and spiri- tuality and to determine the degree to which the personal religious faith of thera- pists is associated with the use of religion and spirituality in counseling. This is accomplished through the use of meta-analysis. The Use of Meta-Analysis as a Statistical Technique Although meta-analysis often involves aggregating results from experimental studies, it can also be used in aggregating correlational data, as was done in this meta-analysis. As Rosenthal (1991) explained, the only constraint in determining the relationship between two variables is that the relationship be of interest to the investigator. The investigator deterrrvines relationships between variables by obtairung an estimate of the effect size between two variables, which some studies do

- 55. not provide along with their tests of significance (Rosenthal, 1991). In these instances, the test of sig- riificance that is provided (whether yj^, t, or F) is transformed to an r for the purpose of computing an overall averaged r across studies. Hvmter and Schmidt (1990) noted that one criticism of the meta-analysis of correlations is that it typically provides a slightly downward bias in the esti- mate of population correlations. In practical terms, this is not problematic; if anything, such correlations are more conservative estimates of the relationship between two variables. In the current meta-analysis, we considered several issues to be relevant. The first issue we considered was the personal religion and spirituality of therapists. As mentioned earlier, this information is used to determine how differ- ent the culture of counselors might be from their clients and, thus, how the need for respect for, and comfort dealing with, cultures other than one's own might present Counseling and Values • October 2004 • Volume 49 71 in a counseling situation. A second issue we considered concerned therapists' personal religiousness and their use of explicit integration of religion and spiritu-

- 56. ality in counseling. This information is used to inform how therapists' personal religiousness may relate to their helping styles with religious clients. Finally, we made comparisons, where possible, between samples that were iden- tified as containing explicitly religious therapists and sample groups that may have contained a mix of secular and religious therapists. We also made comparisons between therapists from different professional backgrounds to understand how each of the multicultural competencies (respect for cultures other than one's own, one's helping style as a therapist) might be different across professions. Method Literature Search We identified studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis using literature searches in the PsycINFO and Dissertation Abstracts International databases using the search terms counseling and religion, counseling and spirituality, psychotherapy and religion, a n d psychotherapy and spirituality. We sought unpublished studies, such as unpublished doctoral dissertatior^, in order to reduce die "file drawer problem" identified by Rosenthal (1979), in which the meta-analysis indicates a higher effect size than actu- ally exists because studies with nonsigruJficant effects have not been located.

- 57. We identified 40 studies through the literature search. Of those studies, we elimi- nated six dissertations because they were not empirical. We eliminated three other empirical dissertations because they did not contain variables of interest. We elimi- nated a final dissertation because it was not available, and the author did not respond to an e-mail message that had been sent. We eliminated 2 published studies by explicitly Christian therapists (Ball & Goodyear, 1991; Worthington, Dupont, Berry, & Duncan, 1988) because they were methodologically different from the other studies, making it impossible to include them in the meta- analysis. Two studies (Bergin & Jensen, 1990; Jensen & Bergin, 1988) were of the same sample. We considered these to be 1 study. One study (Sorenson & Hales, 2002) was a new analysis of two samples already included in the total data set, so this study was reviewed but not included in the analyses. Thus, the final number of studies included in the analyses was 26. Demographic Characteristics of the Total Sample We aggregated the demographic characteristics of the total sample across stud- ies to describe the sample. Regarding professional backgrounds, clinical and coun- seling psychologists composed 44.15% of the total sample, explicitly Christian counselors 21.30%, marriage and family therapists 14%, social workers 5.85%,

- 58. psychiatrists 4.32%, explicitly Mormon psychotherapists 3.54%, psychotherapists 2.77%, licensed professional counselors 1.82%, and pastoral counselors 1.71%. (Per- centages do not total 100 due to rounding.) With respect to gender, men composed 58.11% of the sample, and women composed 41.89% of the sample. The sample ranged in age from 22 to 89 years, with a mean age of 46.1. Only five studies re- ported the race of the therapist sample. The authors of those five studies estimated 72 Counseling and Values • October 2004 •Volume 49 the percentage of White therapists to be 83% to 95% (Bilgrave & Deluty, 1998,2002; Case & McMinn, 2001; Forbes, 1995; Sheridan, Bullis, Adcock, Berlin, & Miller, 1992). Computation of Effect Size First, we converted all relationships of interest to an r, and then we calculated a weighted overall averaged r by weighting each individual correlation by the sample size associated with each individual study. Second, we calculated the overall sig- nificance level of each correlation by the method of adding z scores. Following the technique proposed by Rosenthal (1991), we added z scores from samples and then divided the sum of the z scores by the square root of the number of studies. Third,

- 59. we compared the significance of several correlations using Fisher's test of signifi- cance between independent correlations (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). We used appen- dixes from Cohen and Cohen to transform correlations to z scores. Then, we divided the difference between the z equivalents by the standard error to obtain a normal curve deviate. We used appendixes provided in Cohen and Cohen to obtain the p value for the significance test. Finally, we added the raw scores from some items of interest (such as religious denomination) across studies. Results Personal Religion and Spirituality of Therapists Religious affiliations of therapists from mixed samples were provided in 18 studies of 3,813 therapists. The majority of therapists in these samples were Protestant (34.51%), Jewish (19.61%), or Catholic (13.89%). Religious denominations among therapists from different professional backgrovinds are presented in Table 1. Clinical and counseling psychologists were more likely to be either an agnostic (x̂ = 10.27, p < .005) or atheist (x̂ = 27.19, p < .005) when compared with marriage and fam- ily therapists but were not more likely to be either an atheist or agnostic when compared with social workers. Clinical and counseling psychologists were also more likely to endorse no religion than either marriage and family therapists

- 60. (X ̂ = 34.13, p < .0001) or social workers (x̂ = 7.98, p < .01). Five studies (N = 1,738) of therapists from mixed samples and 2 studies (N = 762) of explicitly religious therapists reported frequency of therapists' participation in organized religion or church activities. Among therapists from mixed samples, 21.1% reported being inactive, whereas 44.8% reported being active. Among explicitly religious therapists, only 8.79% reported being inac- tive, compared with a majority (82.54%) who reported being active. With respect to professional background, more marriage and family therapists were active (59.58%, 2 studies, N = 438) than either secular clinical and counseling psy- chologists (39.75%, 5 studies, N = 1,122) or psychiatrists (32%, 1 study, N = 71). Psychiatrists also endorsed inactive (68%) more frequently than either clini- cal and counseling psychologists (54.63%) or marriage and family therapists (16.21%). Possible reasons for these findings may have been that 15% of the sample in Winston's (1991) study of marriage and family therapists was com- posed of pastoral counselors, as well as the fact that psychiatrists were repre- sented in only a small, single sample. Counseling and Values • October 2004 • Volume 49 73

- 61. TABLE 1 Differences in Religious Denomination by Professional Background Affiliation Protestant Jewish Catholic Atheist Agnostic No religion Other Psychoiogists* N 593 339 250 31 74 270 297 % 35.85 20.49 15.11 1.87 4.47 16.32

- 62. 17.96 Marriage and Famiiy Therapists" N 433 110 126 3 6 71 117 % 50.0 12.7 14.6 0.03 0.07 8.2 13.5 Sociai Workers' N 109 56 32 3 6

- 63. 27 39 % 40.1 20.6 11.8 1.1 2.2 9.9 14.3 Note. Percentages do not total 100 due to rounding. °Ten studies. ""Six studies. 'Three studies. Six studies (JV = 1,678) were used to calculate frequency of personal spiritual practices (such as prayer or meditation). We observed large differences between therapists from mixed samples (4 studies, N=916) and explicitly religious (2 stud- ies, N = 762) therapists. Among therapists from mixed samples, 40.6% reported engaging in personal spiritual practices on a weekly or daily basis compared with 78.8% of explicitly religious tiierapists. Among therapists from mixed samples, 45.5% reported engaging in personal spiritual practices infrequently or never compared with orJy 9.1% of explicitly religious therapists. Religion and Spirituality in Counseling

- 64. To determine how often therapists use religious or spiritual techniques in counseling, we added responses and then averaged them across eight stud- ies (total N = 2,253). Four studies (N = 1,102) of therapists from mixed samples reported on the number of therapists who had previously used a religious or spiritual technique in therapy. The majority of therapists from mixed samples (66.6%) reported using prayer in therapy; 64.1% reported using religious language, metaphors, and concepts in therapy; and a minority (44.4%) reported using scripture in therapy. Four studies (N = 1,037) reported explicitly religious therapists' frequency of using spiritual or religious techniques with religious clients rather than the percentage of those therapists who had used a technique before. Among explicitly religious therapists, forgiveness was used in 42.2% of therapy cases, use of scripture/teaching of biblical concepts in 39.2%, confrontation of sin in 32.6%, and religious imagery in 18.2% of therapy cases. Prayer is a spiritual technique that has been studied in several ways among ex- plicitly religious therapists. Three studies (N = 1,097) reported that 73.6% of explic- itly religious therapists prayed for their clients outside of session. Five studies (N= 1,372) reported therapists' frequency of in-session prayer with

- 65. clients. In those five studies, therapists used in-session prayer in 29.1% of therapy cases. We calculated separate overall averaged rs for therapists from mixed samples and explicitly religious therapists to determine the relationship between thera- 74 Counseling and Values • October 2004 • Volume 49 pists' personal religious faith and therapists' frequency of use of religious and spiritual techniques in counseling. Authors of the studies that examined therapists' use of religious and spiritual techniques in counseling typically summed a list of individual religious and spiritual techniques and then cor- related that scale with a self-report measure of either religious attitudes or religious behaviors. The overall averaged r among therapists from mixed samples (using six studies, N = 873) was .24, p < .0002. The correlation among explicitly religious therapists was higher, overall averaged r = .41, p < .0001. We also calculated separate overall averaged rs for therapists from different professional backgrounds to determine the relationship between therapists' per- sonal religious faith and use of spiritual techniques in counseling. The overall

- 66. averaged r for marriage and family therapists was .12, p = .005. The correlation among clinical psychologists was higher, overall averaged r = .30, p < .001. We conducted a series of tests of the difference between correlations using Fisher's comparison of r (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). The correlation between personal faith and therapists' use of spiritual techniques among explicitly religious therapists was significantly higher than the same correlation among therapists from mixed samples, p < .0001. Only one study (Forbes, 1995) com- puted a correlatiori between training in religious and spiritual issues and use of spiritual techniques in therapy (r = .38). This correlation was not statisti- cally significantly different from the correlation between personal faith and use of spiritual techniques among explicitly religious therapists {p = .12). Fi- nally, the correlation between personal religious faith and use of spiritual tech- ruques among marriage and family therapists in mixed samples was compared with the same correlation among clinical psychologists from mixed samples. This correlation was significantly higher for clinical psychologists {p = .004). Finally, we calculated the frequency with which therapists from mixed samples discussed religion and spirituality issues during training using four

- 67. studies {N = 1,156). The majority of therapists (82%) reported that they never or rarely discussed religious or spiritual issues in training, 13.6 % stated that they sometimes did, and 4.3% reported they discussed them often. Relationship of Personal Religion to Counseling-Related Variables We calculated the relationship between therapists' personal religiousness and opermess to discussing religious issues in counseling using an overall aver- aged r. The overall averaged r among therapists from mixed samples (3 stud- ies, N = 216) was equal to .37, p < .02, compared with an overall averaged r of .39, p = .007, using all 4 studies, and with .40 in the Jones, Watson, and Wol- fram (1992) study of religious therapists. These correlations were not statisti- cally different. Finally, we calculated an overall averaged r between the personal religious faith of the therapist and therapist theoretical orientation among thera- pists from mixed samples (5 studies, N = 1,474). This correlation was equal to .25, p < .001. (As noted earlier, Sorenson & Hales, 2002, performed a reanalysis of two data sets already included in the meta-analysis. As part of an analysis of covariance including other variables, they found that religious therapists trained at secular programs were significantly more likely, F[l, 396] = 19.82,

- 68. Counseling and Values • October 2004 "Volume 49 75 p < .001, to use explicit religious and spiritual interventiors thari were reli- gious therapists trained at explicitly religious training programs.) Discussion One issue we examined in this study was the religious and spiritual cultural heritage of psychotherapists. The results confirm that the religious and spiri- tual cultural heritage of psychotherapists differs from that of the average American. Indeed, the majority of therapists from mixed samples were affili- ated with a religious denomination but were largely inactive within organized religion. This contrasts sharply with the general U.S. population, because approximately 40% of Americans attend church on a weekly basis (Hoge, 1996). In addition, although the majority of psychotherapists claim that spirituality is relevant to them, most engage in personal spiritual practices infrequently, whereas approximately two thirds of Americans consider spiritual practices such as prayer an important part of their daily lives (Hoge, 1996). Thus, if a therapist comes from a religious and spiritual cultural heritage that differs

- 69. from the client's, he or she should consider the potential impact of their cul- tural differences on the course of treatment. Therapists' religious cultural heritage may be an especially salient issue for clinical and counseling psychologists, who were more likely to endorse athe- ism, agnosticism, or no religion than either marriage and family therapists or social workers. Among Americans claiming a religious affiliation, the majority of them (56.6%) are Protestant, followed by Catholic (37.8%), with people from Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, or other religious backgrounds composing the remaining 5.5% of religious people in America (Keller, 2000). Thus, religious cultural differ- ences with regard to denomination (as well as the beliefs and practices associ- ated with being in a denomination) between client and therapist are likely to exist, particularly for clinical and counseling psychologists. Clinical and counseling psychologists who find it difficult to understand the cultural heritage of clients who practice their spirituality within the context of an organized religion may wish to consult with explicitly religious therapists on such therapy cases. Explicitly religious therapists were more similar to the ma- jority of Americans, as measured by previous polls (e.g., GaUup & Lindsay, 1999), with respect to religious affiliations and personal spiritual practices. Thus, ex-