Transfer of Title by Non Owner.pptx

- 1. Transfer of Title by Non-Owners Lyla Latif, PhD

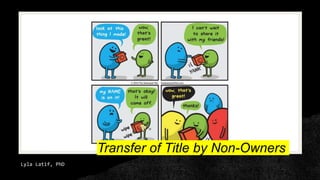

- 2. When can a buyer become the legal owner of goods, notwithstanding that the seller is neither the owner of them, nor sold them with the owner’s consent? Should an innocent purchaser for value without notice of the defect in title suffer due to the dishonesty of the seller?

- 3. Property and Title Property – this term is used when referring to the nature of the seller’s obligations to the buyer in respect of the ownership of the goods and to the exact time when ownership is transferred to the buyer under a contract of sale. So, we speak of has property been transferred? When is property to be transferred? Title – this term is used to consider the various circumstances in which a buyer may become the owner of the goods, notwithstanding that the seller is neither the owner or them nor sold them with the seller’s consent. Here we ask, who is the owner? Example: Greenwood v Bennett & Others (1973)

- 4. Nemo dat Nemo dat quod non habet – is a Latin maxim which translates as ‘no one gives who possesses not’. It broadly provides that a seller can only transfer to a buyer the ownership in the goods if he owns them or has the right to sell them at the time of sale. A seller who does not own the goods and who is not authorised by the owner to sell them cannot usually pass good title to an innocent buyer. The nemo dat rule protects the true owner of the goods at the expense of the innocent purchaser who loses out.

- 5. Bishopgate Motor Finance Corporation Ltd v Transport Brakes Ltd “In the development of our law, two principles have striven for mastery. The first is for the protection of property: no one can give a better title than he himself possesses. The second is for the protection of commercial transactions: the person who takes in good faith and for value without notice should get a good title. The first principle has held sway for a long time, but it has been modified by the common law itself and by statute so as to meet the needs of our own times” Lord Denninh

- 6. Section 21(1) SOGA, 1979 • Section 21(1): Subject to this Act, where goods are sold by a person who is not their owner, and who does not sell them under the authority or with the consent of the owner, the buyer acquires no better title to the goods than the seller had, unless the owner of the goods is by his conduct precluded from denying the seller’s authority to sell.

- 7. Exceptions to the nemo dat rule SOGA, 1979 FACTORS ACT, 1889 HIRE PURCHASE ACT, 1964 COMMON LAW Section 21.1 – Estoppel Section 23 – Voidable title not avoided at the time of sale Section 24 - Sale by seller in possession after sale Section 25 – Sale by buyer in possession after sale Section 47.1 – resale by buyer not in possession but with seller’s assent Sec 62.2 – Sale by agent with consent Secs 1.1. and 2 – Sale by a mercantile agent Sec 8 – Sale by a seller in possession after sale Sec 9 – Sale by a buyer in possession after sale Sec 27 – Bona fide private purchaser of a motor vehicle from a person in possession under a Hire Purchase agreement or a conditional sale Third part purchases goods from a dealer acting in the ordinary course of business where those goods were entrusted to the dealer by their true owner

- 8. • Estoppel • Sale under a voidable title • Sale by seller in possession after sale • Sale by buyer in possession after sale

- 9. 1. Estoppel This doctrine is set out in section 21.1 of SOGA, 1979 – basically stating that the owner of goods can be precluded from denying the seller’s authority to sell because of the owner’s own conduct. Shaw v Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis (1987): Held: Owner’s action in signing the letter and transfer slip amounted to conduct within the meaning of sec 21.1. He was therefore estopped from denying the swindler’s authority to sell. But because the bankers draft was dishonoured – Shaw also did not obtain good title to the vehicle as property in it had not passed to him.

- 10. Estoppel by representation This is where the owner of the goods by his words or conduct represents to the buyer: • that the seller is the true owner of the goods • or has his authority to sell the goods Can also be further divided into: • estoppel by words and • estoppel by conduct

- 11. Farquharson + Eastern Distributors + Central Newbury • Farquharson Brothers v King (1902): timber merchants who authorised Capon to sell the timber to specific buyers. Capon, acts fraudulently selling to King. Held: Because F did not introduce Capon to King, they could not be estopped from denying Capon’s authority to sell. Capon had no authority to sell to King. His authority was limited to selective buyers he could not transfer good title to King and F was entitled to recover from King the value of the timber. • Eastern Distributors Ltd v Goldring (1957). Held: when approaching the plaintiff, Murphy intentionally represented to them that the van was owned by Coker he was therefore estopped from asserting ownership over it. The plaintiffs could recover the van from Goldring. • Central Newbury Car Auctions Ltd v Unity Finance Ltd (1957) –it was held that the mere handing over of a motor car together with its registration book does not, without more, constitute a representation that the person in receipt of the goods is entitled to deal with the car as owner.

- 12. Estoppel by negligence • Moorgate Mercantile Co Ltd v Twitching (1977) – a hirer hired a car from Moorgate who failed to register the hire purchase transaction with a company called HPI. Registration was not compulsory, but majority of transactions were registered to prevent fraud. The hirer sold the car to Twitching. The problem here is that the hirer had not finished paying the instalments, he therefore had no right to sell the car. Twitching contacted HPI to check if the car was registered and to check if it had any outstanding balances. Since the car was not registered, Twitching noting that it was free of encumbrances purchased it. Moorgate found out and sued. Twitching claimed estoppel by negligence. Held: HL – estoppel did not apply- registration was not compulsory, Moorgate had no duty that he breached.

- 13. 2. Sale under a voidable title • Rule 1 – if the seller’s title is void, the buyer gets no title at all. • Rule 2 – if the seller’s title is voidable, the buyer may acquire the title. • Ingram v Little (1961) • Lewis v Averay (1972) • Cundy v Lindsay (1878) • Shogun Finance Ltd v Hudson Face to face - unless the specific identity of the party is of some particular significance, the innocent party can be presumed to have intended to deal with the person in front of them, so that any fraud as to their identity merely renders the contract voidable. Distance - a contract concluded at a distance, especially one in writing, which by necessity identifies specifically who the contracting parties are, the contract can be taken to have been intended between those parties alone, so that where a fraudster forges the signature of one of the parties the result is that the contract is void. • Car & Universal Finance Co Ltd v Caldwell (1965)

- 14. 3. Sale by a seller in possession after sale

- 15. 4. Sale by buyer in possession after sale

- 16. Helby v Matthews (1895) • For section 25 to apply certain conditions need to be satisfied: The third party must buy or agree to buy the goods from the buyer in possession The sale cannot be a sale based on hire purchase or under a sale or return contract it has to be an unconditional sale The third party will only be protected under sec 25 if the goods or documents of title were in the possession of the first buyer (the buyer in possession) with the consent of the seller There must be delivery or transfer of the goods or documents of title to the third party by the buyer in possession under a sale pledge or other disposition

- 17. National Employers’ Mutual General Insurance v Jones (1990) • Held: The House of Lords held that the purpose and scope of the Factors Act 1889 was to protect those dealing in good faith with mercantile agents to whom goods or documents of title had been entrusted by the true owner to the extent that their rights overrode those of the true owner. The Act was not, however, intended to enable a bona fide purchaser to override the true owner’s title where the agent had been entrusted with the documents or goods by a thief or even a purchaser from a thief. As a result, Jones had not acquired title to the car under s 9 and the insurance company was therefore entitled to recover the value of the car from Jones.

- 18. The End