art. 4 (Y. Polo)

- 1. ARTICLE JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS Burnham OF MARKETING SCIENCE 10.1177/0092070302250897 SPRING 2003 Consumer Switching Costs: A Typology, Antecedents, and Consequences Thomas A. Burnham Santa Clara University Judy K. Frels University of Maryland Vijay Mahajan University of Texas at Austin The management of customer switching costs has been In view of the potential importance of switching costs, the impact of all strategic moves on switching hampered by the lack of a comprehensive typology for con- costs should be considered. ceptualizing, categorizing, and measuring consumers’ perceptions of these costs. This research develops a —Michael Porter (1980:122). switching cost typology that identifies three types of switching costs: (1) procedural switching costs, primarily Reduced regulation, increased price competition, and involving the loss of time and effort; (2) financial switching diminished consumer loyalty have propelled customer costs, involving the loss of financially quantifiable re- retention and customer relationship management (CRM) sources; and (3) relational switching costs, involving psy- to the forefront of marketing concerns (Marketing Science chological or emotional discomfort due to the loss of Institute 2002). As the primary tool for managing cus- identity and the breaking of bonds. The research then ex- tomer retention, customer satisfaction has received amines the antecedents and consequences of switching unflagging attention in the marketing literature (cf. Ander- costs. The results suggest that consumers’ perceptions of son and Sullivan 1993; Fornell 1992; Fournier and Mick product complexity and provider heterogeneity, their 1999; Szymanski and Henard 2001). Firms around the breadth of product use, and their alternative provider and world have adopted customer satisfaction measures as a de switching experience drive the switching costs they per- facto standard for monitoring progress, motivated by the ceive. Furthermore, all three switching cost types signifi- belief that customer retention and profitability will follow. cantly influence consumers’ intentions to stay with their While evidence accumulates that satisfaction influences current service provider, explaining more variance than repeat purchase behavior, it typically explains only a quar- does satisfaction. ter of the variance in behavioral intentions (see the meta- analysis by Szymanski and Henard 2001), and the rela- Keywords: switching costs; customer satisfaction; cus- tionship between satisfaction and loyalty is now recog- tomer retention; customer loyalty; customer nized as more complex than originally proposed (Fournier relationship management and Mick 1999; Mittal and Kamakura 2001; Oliver 1999). Yet firms appear to be stuck in a “satisfaction trap,” a myo- pic belief that customer satisfaction and service quality are the only tools for managing customer retention (Reichheld Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1996). To break out of this trap, marketers must devote Volume 31, No. 2, pages 109-126. themselves to more fully understand the various drivers of DOI: 10.1177/0092070302250897 customer retention. This research investigates an oft- Copyright © 2003 by Academy of Marketing Science.

- 2. 110 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 noted, but seldom studied, driver of repeat choice behav- • Provide an assessment of major theoretical factors ior: the switching costs that reduce customers’ desire to that drive consumer switching cost perceptions leave an incumbent provider. • Assess the effects of different types of switching costs on consumers’ repeat purchase intentions Firms regularly make marketing choices that affect consumers’ perceived switching costs. Consider an exam- To achieve these objectives, we develop a comprehen- ple from the U.S. long-distance telephone industry. In sive two-tiered typology for conceptualizing consumer 1991, MCI launched the Friends & Family program. This switching costs using data from two consumer service in- marketing program asked customers to invest time and dustries. At the lower level, the typology provides the effort building “circles,” or databases of friends and family granularity necessary to assess distinct switching cost fac- members, in order to receive a discounted calling rate. ets. At the higher level, it offers the parsimony required to Between 1991 and 1997, MCI gained almost five share efficiently conceptualize and communicate the construct. points in the long-distance market. In 1995, AT&T Using this typology, we first test a model of switching cost scrapped its long-standing use of time-varying prices and antecedents. We then examine how different switching began offering a 10¢ a minute plan for all long-distance costs explain consumers’ intentions to stay with an incum- calls. Between 1991 and 1997, AT&T lost 18 percent of bent provider. Drawing on the study findings, recommen- the market it had once dominated. While additional factors dations are presented for managing the factors that are likely to have influenced these share changes, we sug- influence consumer switching costs and for using switch- gest that the AT&T pricing change reduced the costs its ing costs, along with customer satisfaction, in programs to customers faced in comparing alternatives and thus weak- improve customer retention. We conclude with a discus- ened AT&T’s customer retention. The MCI Friends & sion of the generalizability of the findings and future re- Family program, on the other hand, increased the time and search directions. effort investments its customers would lose upon switch- ing and thus strengthened MCI’s customer retention. In the marketing, management, and economics litera- THE SWITCHING COST CONSTRUCT ture, a consensus has emerged that switching costs are prevalent in a wide variety of industrial and consumer con- Definition of Switching Costs texts (Fornell 1992; Klemperer 1995). There is evidence that switching costs have a significant impact on repeat Porter (1980) suggested that switching costs are “one- choice behavior (Weiss and Heide 1993), on the strategies time” costs (p. 10), as opposed to the ongoing costs managers should (and do) adopt (Eliashberg and Robert- associated with using a product or provider once a repeat- son 1988; Karakaya and Stahl 1989), and on the resultant purchase relationship is established. We define switching industry and competitive structures (Farrell and Shapiro costs as the onetime costs that customers associate with 1988). Switching costs have also been associated with the process of switching from one provider to another. higher profits (Beggs and Klemperer 1992), with inelastic While switching costs must be associated with the switch- response to price (Farrell and Shapiro 1988), with ing process, they need not be incurred immediately upon increased product preannouncements (Eliashberg and switching. Furthermore, switching costs need not be lim- Robertson 1988), and with barriers to market entry and ited to objective, “economic” costs. When consumers sim- sustainable strategic advantage (Karakaya and Stahl 1989; plistically state that “it’s just not worth it” to switch pro- Schmalensee 1982; Kerin, Varadarajan, and Peterson viders, they may perceive impediments ranging from 1992). “search costs, transaction costs, learning costs, loyal cus- Given their importance, it seems natural that firms tomer discounts, customer habit, emotional cost and cog- would want to manage their customers’ perceptions of nitive effort, coupled with financial, social, and psycho- switching costs. Regrettably, the existence of perceptions logical risk on the part of the buyer” (Fornell 1992:10). of switching costs has, by and large, been supported by These costs are seldom explicitly assessed, but they anecdotes, logic, and simplistic measures that do not become salient and evident when consumers are faced reflect the multidimensional nature of switching costs dis- with a reason to consider switching. cussed in the literature. There is little surprise, then, in the calls for solid empirical research on the switching cost A Comprehensive View of Switching Costs construct and its management (Gatignon and Robertson 1992; Klemperer 1995). To effectively manage switching costs, firms must dis- The primary objectives of this research are the following: tinguish and understand the various types of costs that con- sumers perceive. Regrettably, descriptions of switching • Discover and empirically validate a typology of con- cost facets (e.g., Porter 1980; Jackson 1985; Guiltinan sumer switching cost perceptions 1989; Klemperer 1995) have yet to be supported by empir-

- 3. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 111 Switching Cost Facet Definitions ical research, leaving both researchers and practitioners without accepted frameworks or measurements to draw 1. Economic risk costs are the costs of accepting uncer- on. This is understandable. As Fornell (1992) stated, “A di- tainty with the potential for a negative outcome when rect measure of switching barriers is difficult to obtain” as adopting a new provider about which the consumer has “all costs associated with deserting one supplier in favor of insufficient information (Guiltinan 1989; Jackson 1985; another constitute switching barriers” (p. 11). A review of Klemperer 1995; Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988). Per- empirical switching cost literature reveals that prior re- ceived consumption risk has been conceptualized as a six- search has typically adopted one of three approaches to dimensional construct (Bettman 1973), three of which are measuring switching costs: relevant here: performance risk, financial risk, and conve- nience risk. • It has measured one or a few switching cost facets 2. Evaluation costs are the time and effort costs associ- specific to the context of the research, such as a ven- ated with the search and analysis needed to make a switch- dor’s retraining effort, their process development ef- ing decision (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; Shugan fort, and their relationship development time (cf. 1980). Time and effort are associated with collecting the Heide and Weiss 1995). information needed to evaluate potential alternative pro- • It has measured switching costs as a unidimensional viders. Mental effort is required to restructure and analyze global construct. For example, “How costly would it available information in order to arrive at an informed be for you to switch suppliers?” (cf. Eliashberg and decision (Shugan 1980). Robertson 1988; Karakaya and Stahl 1989; Ping 3. Learning costs are the time and effort costs of acquir- 1993). ing new skills or know-how in order to use a new product • It has assumed that consumers perceive switching or service effectively (Alba and Hutchinson 1987; Eliash- costs and has ascribed all evidence of differences in berg and Robertson 1988; Guiltinan 1989; Wernerfelt satisfaction response to such costs (cf. Anderson and 1985). Learning investments are often provider-specific, Sullivan 1993; Fornell 1992; Klemperer 1995). meaning new investments must be made to adapt to a new provider (Klemperer 1995). While each of these approaches may be appropriate for its context, reliance on them leaves gaps in our understand- 4. Setup costs are the time and effort costs associated ing of switching costs, their drivers, and their impact on with the process of initiating a relationship with a new pro- customer retention. Examining a single facet of a multifac- vider or setting up a new product for initial use (consider eted construct is unlikely to produce an adequate assess- installing and configuring software) (Guiltinan 1989; ment of the construct or its relationships with other Klemperer 1995). Setup costs for services are dominated constructs (Kumar, Stern, and Achrol 1992), while em- by the information exchange needed for a new provider to ploying a global measure provides little guidance for man- reduce its selling risks and understand the customers’ spe- aging switching cost perceptions and increases measure- cific needs (Guiltinan 1989). ment error as it forces respondents to mentally combine 5. Benefit loss costs are the costs associated with con- multidimensional ratings. Relying on regression inter- tractual linkages that create economic benefits for staying cepts to represent switching costs not only combines the with an incumbent firm (Guiltinan 1989). In switching to a effects of multiple switching cost types but also confounds new provider, consumers may lose points they have accu- switching costs with other possible influences on repeat mulated and discounts or benefits that are not afforded to purchase behavior. A more rigorous means for conceptual- new customers (Guiltinan 1989). izing and measuring consumer switching costs is needed. 6. Monetary loss costs are the onetime financial outlays that are incurred in switching providers other than those A Switching Cost Typology used to purchase the new product itself (Heide and Weiss 1995; Jackson 1985; Klemperer 1995; Porter 1980; Weiss and Heide 1993). Adopting a new provider often involves On the basis of a review of the literature and interviews onetime expenditures such as deposits or initiation fees for with industry managers and consumer focus groups, we new customers (Guiltinan 1989). In addition, switching developed multi-item scales for comprehensively measur- products or providers may involve replacing transaction- ing consumer switching costs. Following accepted scale specific assets, or “coassets,” in which the consumer has development procedures (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; invested (Kerin et al. 1992; Weiss and Heide 1993). Churchill 1979), we found evidence for eight distinct switching cost facets. The facets are described next; the 7. Personal relationship loss costs are the affective methodology by which they were derived is presented later losses associated with breaking the bonds of identification in the Method and Results section. that have been formed with the people with whom the

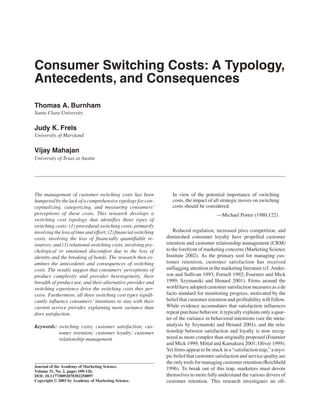

- 4. 112 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 SWITCHING COST ANTECEDENTS FIGURE 1 A Typology of Consumer Perceptions of Prior research suggests a number of strategies for man- Switching Costs aging specific consumer switching costs (e.g., Crosby, Evans, and Cowles 1990; Klemperer 1995). However, these suggestions support a piecemeal approach to switch- Relational Procedural Financial Switching Costs Switching Costs Switching Costs ing cost management, raising a number of concerns. First, managing distinct switching costs separately may be less • Economic • Benefit • Personal Risk Costs effective than managing them simultaneously, as certain Loss Costs Relationship • Evaluation Loss Costs • Monetary antecedents may influence multiple switching costs. Sec- Costs • Brand Loss Costs • Set Up Costs ond, without a thorough understanding of switching costs Relationship • Learning Costs Loss Costs and their antecedents, a firm may fail to recognize when its actions will influence switching costs—as AT&T’s sim- plification of its pricing structure did—and the firm may inadvertently reduce some of its customers’ switching costs. To provide a framework for managing different types of switching costs, we propose hypotheses linking six antecedents with the three major switching cost types customer interacts (Guiltinan 1989; Klemperer 1995; Por- (see Figure 2). ter 1980). Consumers’ familiarity with incumbent pro- vider employees creates a level of comfort that is not Switching Cost Antecedents and Hypotheses immediately available with a new provider. 8. Brand relationship loss costs are the affective losses Prior research suggests three groups of consumer- associated with breaking the bonds of identification that based antecedents of switching costs: have been formed with the brand or company with which a customer has associated (Aaker 1992; Porter 1980). Con- • Perceptions of product and market characteristics sumers often draw meaning from their purchases and form (Gatignon and Robertson 1992) associations that become part of their sense of identity • Investments with the provider (Jackson 1985) (McCracken 1986). These brand- or company-based rela- • Domain expertise (Alba and Hutchinson 1987; tional bonds are lost in switching providers. Klemperer 1987; Wernerfelt 1985). Switching Cost Types Perceptions of Product and Market Characteristics Product and market characteristics describe the nature To provide a more parsimonious typology of switching of the products and providers in an industry. Switching costs, we investigated the relationships between the eight costs may be generated by product and market characteris- switching cost facets. Analyses described in the Method tics associated with a slow diffusion of innovations. Two and Results section suggested that the eight facets could be such characteristics are the complexity of the items being further organized as three higher-order switching cost considered (Gatignon and Robertson 1992; Klemperer types (see Figure 1). These were titled as follows: 1995) and the heterogeneity of providers in the market (Schmalensee 1982). Since perceptions of these character- • Procedural switching costs: Consisting of economic istics vary among consumers within an industry, differ- risk, evaluation, learning, and setup costs, this type ences in switching costs occur as well. of switching cost primarily involves the expenditure 1 Product complexity is defined as the extent to which the of time and effort. consumer perceives a product to be difficult to understand • Financial switching costs: Consisting of benefits loss or use (Rogers 1995). A product that offers a large number and financial-loss costs, this type of switching cost 2 of options or that involves a large number of steps in its use involves the loss of financially quantifiable resources. will typically be seen as more complex. Consumers are • Relational switching costs: Consisting of personal- likely to perceive higher risks when products are more relationship loss and brand relationship loss costs, complex because the difficulty in understanding the prod- this type of switching cost involves psychological or uct leads to uncertainty, increasing the perception that an emotional discomfort due to the loss of identity and unknown negative outcome may occur (Holak and the breaking of bonds. Lehmann 1990). Similarly, the larger number of attributes In the next section, we investigate the factors that drive associated with complex products makes both information consumers’perceptions of these three switching cost types collection and direct comparisons of attributes more costly in order to understand how they might be better managed. (Shugan 1980). A more complex product is also likely to

- 5. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 113 FIGURE 2 Consumer Switching Costs and Their Antecedents and Consequences (Theoretical Model) Market Characteristics • Product Complexity H1 + • Provider Heterogeneity H2 Procedural Switching Costs + • Economic Risk Costs • Evaluation Costs Consumer Investments • Learning Costs • Breadth of Use • Set-Up Costs H3 H8 + Intention to Stay with Incumbent Provider • Extent of Modification H4 + Financial Switching Costs + • Benefit Loss Costs Domain E xpertise H9 • Monetary Loss Costs • Alternative Experience H5 _ _ + H7 • Relational Switching Costs • Switching Experience H6 _ • Personal Relationship Loss Costs Satisfaction • Brand Relationship Loss Costs Individual-Level Covariates • Time Pressure • Risk Aversion involve a larger number of learned skills or scripts that which knowledge concerning one provider is applicable to must be relearned in order to switch providers (Wernerfelt another provider (Schmalensee 1982), increasing the un- 1985). Finally, complex products are not “easy to try” (Holak certainty and the “cost of thinking” associated with and Lehmann 1990:63); thus, as complexity increases, the switching providers (Shugan 1980). Similarly, the lack of efforts required to establish a new relationship will rise. In standardization implied by heterogeneity suggests that sum, when consumers perceive products as more complex, skills learned for use with one provider may not be appli- they perceive higher procedural switching costs. cable with another (Alba and Hutchinson 1987). Hetero- geneity perceptions may also imply loyalty points or Product complexity is also likely to lead to higher reduced prices cannot be transferred across providers financial switching cost perceptions, as a common source (Klemperer 1987, 1995). Finally, to the extent organiza- of perceived product complexity is a complex price struc- tions are seen as different and unique, consumers perceive ture. In the cellular telephone market, the “product” might stronger bonds of identification with them (Bhattacharya, consist of the cell phone itself, the number of minutes Rao, and Glynn 1995). available during the business day, the number of minutes available on the weekend, the geographic area in which a Hypothesis 2: Greater perceived provider heterogeneity call can be received or placed without additional fees, and will be associated with higher procedural, financial, other services such as voice mail and phone insurance. This and relational switching costs. complexity can lead consumers to perceive that switching to a new offering will involve the outlay of additional funds Investments With the Provider or forfeiture of previously made down payments, start-up fees, or investments in provider-specific assets. Investments in relationships tie the members together; Finally, when products are perceived as more complex, if the relationship is terminated, the investments are lost consumers rely more on relationships with brands and (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Morgan and Hunt 1994; people to ensure that they receive a quality product and to Klemperer 1995). The potential for such loss makes simplify choices (Sheth and Parvatiyar 1995). investments an important driver of switching costs (Jack- son 1985). Consumers invest in a provider when they use Hypothesis 1: Greater perceived product complexity will more of the provider’s different products (Blattberg and be associated with higher procedural, financial, and Deighton 1996) and when they modify the products they relational switching costs. receive from the provider (Bhardawaj, Varadarajan, and Fahy 1993; Robinson 1988). Provider heterogeneity is defined as the extent to which the providers in a market are seen as different or nonsub- Breadth of use of a provider is defined as the extent to stitutable. Provider heterogeneity reduces the extent to which the consumer employs a variety of product types,

- 6. 114 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 features, and functions offered by a provider (Ram and greater communication with the provider or interaction Jung 1990). Blattberg and Deighton (1996) suggested that with the product. The interaction and the resultant match- the degree to which a customer buys complements and ing between the consumers’ needs and the product pro- supplements to the core product determines the intrinsic vided lead to higher personal and brand identification retainability of the customer. Insurance customers, for (McCracken 1986), thus creating higher relationship loss example, often purchase life, health, home, and auto insur- costs. ance from a single company. Grocery store customers may Hypothesis 4: Greater modification of the incumbent take advantage of delis, pharmacies, delivery services, product will be associated with higher procedural, video rental services, and store discount cards in addition financial, and relational switching costs. to buying basic groceries. Given the time and effort sav- ings that a “full-line producer” offers, consumers are likely Domain Expertise to switch either all the products associated with a given provider or none of them (Klemperer 1995). The prospect Expertise in a product domain allows consumers to of switching multiple products increases the risks associ- more rapidly and accurately evaluate options and learn ated with switching providers—not only one product is at new product-related information (Alba and Hutchinson risk of performance, financial, or convenience failure but 1987). Consumers gain domain expertise when they multiple, often interdependent products are placed in jeop- increase their product-related experiences (Park, ardy at once. Furthermore, when considering switching Mothersbaugh, and Feick 1994). Two types of domain- providers, consumers who use more products need to com- level product experience are the breadth of the consumer’s pare alternative providers on a greater number of attributes prior experience with an alternative provider (Fornell (Shugan 1980), they need to set up a greater number of new 1992; Klemperer 1987) and the extent of the consumer’s products or features, and they need to invest in learning switching experience (Nilssen 1992). how to use a greater number of new products or features Alternative experience is defined as the breadth of ex- (Schmalensee 1982). perience the consumer has with the various products, fea- In addition to generating procedural costs, using more tures, and functions offered by a competing service linked products or services is also likely to increase the fi- provider. Broad experience with an alternative provider nancial costs of switching. The greater the breadth of prod- leads to increased expertise with the service, which re- ucts employed, the more likely the customer has duces the uncertainty associated with using a new pro- accumulated benefits that will be lost in switching (con- vider. Greater expertise is also associated with more well- sider the multiproduct discounts offered insurance cus- developed mental structures (Alba and Hutchinson 1987). These structures make encoding and retrieving the infor- tomers), and the more likely that one of the products or mation needed to evaluate new products easier and facili- services will be associated with a new monetary outlay in tate new learning (Alba and Hutchinson 1987). Broad switching. Finally, establishing multiple links with a pro- experience with an alternative provider is also likely to re- vider requires greater interaction with the provider. This duce perceptions of uniqueness of an existing provider, increased personal interaction leads to higher personal and leading to weaker relational bonds with the provider brand identification with the provider (McCracken 1986) (Bhattacharya et al. 1995). and thus to stronger personal and brand relationship bonds with the providers of the service. Hypothesis 5: Greater prior experience with alternative providers will be associated with lower procedural Hypothesis 3: Greater breadth of incumbent provider use and relational switching costs. will be associated with higher procedural, financial, and relational switching costs. Switching experience is defined as the extent to which Modification of a product is defined as the extent to the consumer has switched between providers in the past. which the consumer adapts the product offered so that it Increased switching reduces switching costs by increasing better serves his or her individual needs. For example, the consumer’s familiarity with the process of both switch- MCI customers “build” Friends & Family calling circles ing and learning to use new providers (Nilssen 1992). and program fast-dial codes for their calling cards. Switching experience also implies a reduced duration with Citibank customers have personal photographs embedded the incumbent provider, which means there has been less in their credit cards and arrange cross-service airline mile- time to accumulate benefits that might be lost in switching. age credits. Such modifications must be replicated upon Furthermore, consumers who have switched more have switching providers (Bhardawaj et al. 1993). Similarly, had less time with their current provider to develop brand benefits such as frequent-flyer miles or other points ac- and personal relationship bonds, and they are less likely to quired through modification with the current provider will perceive their provider relationship as unique (Bhatta- be lost upon switching. Finally, modification requires charya et al. 1995).

- 7. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 115 Hypothesis 6: Greater switching experience will be asso- stay with the provider. Put simply, switching costs are dis- ciated with lower procedural, financial, and rela- utilities that consumers would rather not incur. While prior tional switching costs. research has not studied the effects of different switching cost types, evidence of direct switching cost effects has been Individual Characteristics accumulating at the industry level and at the global switch- Individual consumer characteristics are also likely to ing cost level (Anderson and Sullivan 1993; Bansal and influence the extent to which switching costs are per- Taylor 1999; Weiss and Heide 1993). Consistent with these ceived. Two individual-level characteristics associated efforts but offering more specificity in our description of with switching cost perceptions are the consumers’level of switching costs, we propose the following direct relation- time pressure and their level of risk aversion (Jackson ship between switching costs and customer intentions: 1985). These two antecedents were measured and included as covariates; no formal hypotheses regarding Hypothesis 8: Greater (a) procedural, (b) financial, and (c) relational switching costs will be associated with their effects are offered. higher consumer intentions to stay with an incum- To summarize, the antecedent model suggests that bent provider. greater perceptions of complexity and heterogeneity, increased breadth of incumbent provider use, and greater Researchers have also suggested that switching costs product modification will generally be associated with and satisfaction may negatively interact with each other in higher switching costs, while increased experience with an driving customer intentions (Jones and Sasser 1995; alternative provider and increased experience with switch- Jones, Mothersbaugh, and Beatty 2000; Oliva, Oliver, and ing will generally be associated with lower switching costs MacMillan 1992). As switching costs rise, the influence of (see Figure 2). satisfaction on intentions to stay with a provider may de- crease (and vice versa). Oliver (1999) suggested that “sat- SWITCHING COST CONSEQUENCES isfaction is a necessary step in loyalty formation but becomes less significant as loyalty begins to set through The driving force behind managerial interest in switch- other mechanisms,” including “social bonding at the insti- ing costs is the premise that these costs impede customer tutional and personal level” (p. 33). Using a global mea- switching and hence improve customer retention. While sure of switching costs, Jones et al. (2000) found evidence an ample body of research discusses this relationship, of this negative interaction effect. Consistent with these ef- empirical evidence is scant; little is known about the role forts, we propose the following moderating effect for each that different switching costs play in aiding customer of the three major switching cost types: retention. A study of the effects of different types of con- sumer switching costs not only strengthens the Hypothesis 9: The relationship between satisfaction and nomological network for the construct and the typology consumer intentions to stay with an incumbent pro- (Gerbing and Anderson 1988) but also provides insights vider will be weaker (stronger) when consumers perceive higher (lower) (a) procedural switching about the utility of switching costs as a managerial tool. costs, (b) financial switching costs, and (c) rela- Our study of switching cost effects builds on current tional switching costs. research that focuses on satisfaction as the primary driver of customer retention. METHOD AND RESULTS The Drivers of Customer Retention Measuring and Organizing Switching Costs While the role of satisfaction in retaining customers is now perceived as more complex than initially thought Drawing on interviews with long-distance, local tele- (Mittal and Kamakura 2001; Oliver 1999), abundant evi- phone service, and insurance industry managers; two con- dence supports the commonsense expectation that satis- sumer focus groups; and the switching cost literature, a fied customers are more likely to stay with their existing comprehensive list of the potential losses faced by con- providers than are dissatisfied customers (cf. Oliver 1997; sumers when switching providers was compiled. Items for Szymanski and Henard 2001). each switching cost were developed or borrowed from pre- vious research and modified. Based on an expert survey in Hypothesis 7: Greater satisfaction will be associated which 20 managers rated the presence of different switch- with higher intentions to stay with an incumbent provider. ing costs and the level of competition for customers in 15 different consumer industries, two industries were identi- To the extent consumers perceive switching costs or fied for further study. The credit card industry and the long- barriers to leaving a provider, they should be inclined to distance industry were selected as being representative of

- 8. 116 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 business domains in which the providers’battle to improve relationship loss switching costs. Correlations between customer retention could greatly benefit from switching these constructs are provided in part A of Table 1. cost management—industries in which a wide array of The more parsimonious structure was derived by first switching cost perceptions should exist even though it is submitting composite measures for the eight constructs to relatively easy for consumers to switch providers. A pre- a varimax-rotated exploratory factor analysis. The results test survey was conducted using a convenience sample of suggested three higher order switching cost types. The 120 nonacademic employees of a large southwestern uni- three-factor model was then tested using a second-order versity. A strict definition of switching was provided to CFA, modeling the flow of the 30 original switching cost ensure consistent interpretation: respondents were asked items through the eight first-order constructs. This model fit the data well: χ2396 = 769, CFI = .98, NFI = .97, RMSEA to consider dropping their previously identified primary service provider in order to adopt a new provider. Respon- = .056. A CFA for this higher order model was then evalu- dents rated their perceptions of the costs involved in ated in comparison with higher order models with switching using 5-point Likert-type scales. Scales for the dimensionalities both above and below that of the pro- switching costs, the antecedents, satisfaction, and con- posed model. A change in chi-square comparison of alter- sumer intentions were then refined using exploratory fac- native, nested covariance models confirmed that the three- tor analysis, Cronbach’s alpha, and confirmatory factor factor higher order model fit the data significantly better analyses (CFAs) (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Churchill than the best two-factor higher order model (∆χ2 2 = 34, p < 1979). .01) and did not fit significantly worse than the best four- factor higher order model (∆χ2 2 = 4.8, p > .05). Given the The final survey was then distributed to 287 credit card consumers and 288 long-distance consumers. The sample virtue of parsimony, these findings support using a three- included members of a local civic organization, employees factor model to conceptualize consumer switching costs. of two national firms, members of a local church organiza- The validity of pooling at this level was also tested using tion, and employees of a large state university. One hun- multigroup methods—pooling of the two industries did dred fifty-eight completed credit card surveys were not result in a significant degradation of model fit. Load- returned (53%), constituting the sample for the credit card ings of the lower order factors are provided in part B of study. Of the long-distance surveys distributed, 144 sur- Table 1, and correlations among the higher order factors veys were returned (50%) and were usable. are provided in part C of Table 1. Using CFA (AMOS 4.01) (Arbuckle and Wothke Using the criteria set forth by Fornell and Larcker 1999), a measurement model incorporating the eight (1981) to test for discriminant validity, the average vari- switching cost facets described earlier was found to fit the ance extracted for the items of each of the three switching data well (long distance: χ2 377 = 596, Comparative Fit cost types was found to be greater than the squared correla- Index [CFI] = .98, Normed Fit Index [NFI] = .95, root tions for all pairs of factors (see part D of Table 1). Thus, mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .064; the three higher order factors are discriminant. In addition, credit card: χ2 377 = 711, CFI = .97, NFI = .94, RMSEA = each pair of the eight lower order switching costs also met .075). Coefficient alphas for the eight scales in both indus- these criteria except for brand relationship loss costs and tries ranged from .68 to .87 (Table A1). To test for the personal-relationship loss costs. On further inspection, appropriateness of pooling the data, the measurement this pair passed for the long-distance data but not for the model was subjected to multigroup tests constraining all credit card data. Given the conceptual differences in the loadings and correlations to be equal across the two indus- two constructs, both were retained. try data sets. The degradation in model fit was insignifi- cant, suggesting a sufficiently consistent model structure Measuring the Antecedents across industries to support pooling the data to achieve and Consequences more accurate parameter estimation in subsequent analy- ses (χ2 377 = 710, CFI = .99, NFI = .97, RMSEA = .054). Scales measuring the antecedent and consequence con- Following the methods proposed by Anderson and structs were developed and tested in the same iterative Gerbing (1988), convergent and discriminant validity of manner described above. The final versions of the six ante- the scales were examined. All items loaded significantly cedent scales (Table A2) demonstrated good reliability on their intended constructs, suggesting convergent valid- (coefficient alphas ranging from .69 to .92) as well as con- ity (Table A1). Discriminant validity was also supported vergent and discriminant validity; constricting the correla- (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). The eight resultant switch- tion between any two constructs to unity resulted in a sig- ing cost facets are those described in detail earlier: eco- nificant degradation in model fit. All construct pairs also nomic risk, evaluation, learning, set-up, benefits loss, passed the more stringent criteria proposed by Fornell and financial loss, personal relationship loss and brand Larcker (1981) except for one pair in one industry (alternative

- 9. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 117 TABLE 1 Switching Costs Measurement Model Loadings and Correlations Risk Evaluation Learning Set-Up Benefit Money Personal A. Lower Order Switching Cost Facet Correlations Risk 1.00 Evaluation .61*** 1.00 Learning .60*** .49*** 1.00 Set-up .64*** .49*** .56*** 1.00 Benefit .18* .08 .36*** .25 1.00 Money .53*** .35*** .48*** .55*** .50*** 1.00 Personal .33*** .06 .36*** .19** .15* .23** 1.00 Brand .16* –.11 .21** .07 .07 .08 .65*** Procedural Financial Relational B. Loading of Lower Order Facets on Higher Order Types Risk .85*** Evaluation .65*** Learning .75*** Set-up .76*** Benefit .51*** Money .88*** Personal .89*** Brand .87*** C. Higher Order Switching Cost Type Correlation Procedural 1.00 Financial .69*** 1.00 Relational .33*** .25** 1.00 D. Fornell-Larcker Criteria for Discriminant Validity for Higher Order Switching Costs (Average variance extracted on diagonal; squared correlation on off-diagonals) Procedural .87 Financial .47 .66 Relational .11 .06 .87 *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. provider experience and switching experience in the credit (Hypothesis 2) received mixed support, while our hypoth- card industry). The six constructs were therefore retained. esis on the effects of product modification (Hypothesis 4) A four-item satisfaction scale was used to assess respon- was not supported. Finally, although no hypotheses were dents’ general satisfaction, confirmation of expectations, offered regarding the covariates, our results suggest that and distance from the hypothetical ideal product (Fornell risk aversion is significantly related to procedural and rela- 1992). A two-item intentions scale was used to assess con- tional switching cost perceptions and that time pressure is sumers’ intentions to stay with their current service pro- significantly related to procedural switching cost percep- vider. Reliability and convergent validity for these scales tions. The results also supported the hypothesized effects were satisfactory (Table A3). of satisfaction on intentions (Hypothesis 7) and the hypothesized effects of the three switching cost types on intentions (Hypothesis 8a-c). Testing the Structural Model To test for interactions, respondents were split into high, medium, and low groups based on their switching The relationships between the constructs were exam- cost perceptions for each of the three types. A structural ined using structural equation modeling. The results are model linking satisfaction with intentions to stay was then presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4 and are summarized below; constrained to force equal loadings between the high- and implications are discussed in the following section. the low-level switching cost groups. None of the three The results fully supported our hypotheses on the cases exhibited a significant degradation in fit when the switching cost effects of breadth of product use (Hypothe- loadings were constrained. Thus, we did not find support sis 3), alternative provider experience (Hypothesis 5) and for the hypothesized negative interaction between satis- switching experience (Hypothesis 6). Our hypotheses on faction and switching costs (Hypothesis 9). the effects of complexity (Hypothesis 1) and heterogeneity

- 10. 118 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 TABLE 3 TABLE 2 Consequences Structural Model: Antecedents Structural Model: Effects on Intent to Stay Effects on Switching Costs SMC of Standardized Estimates Standardized Intent Procedural Financial Relational Estimates to Stay Conclusion Costs Costs Costs Conclusion Combined model Hypothesis 1: Hypothesis 7: Satisfaction .30*** .31 Supported Complexity .60*** .31*** .05 Mixed support Hypothesis 8a: Procedural costs .20** Supported Hypothesis 2: Hypothesis 8b: Financial costs .15* Supported Heterogeneity .12* .05 .37*** Mixed support Hypothesis 8c: Relational costs .30*** Supported Hypothesis 3: 2 Model fit: χ 1,858 = 3,416, CFI = .97, NFI = .93, p < .000, Breadth of use .21*** .30*** .28*** Supported RMSEA = .053 Hypothesis 4: Modification –.10* .00 .07 Not supported Satisfaction only model Hypothesis 5: Satisfaction .40*** .16 Alternative 2 Model fit: χ 1,861 = 3,477, CFI = .97, NFI = .93, p < .000, experience –.21*** — –.16* Supported RMSEA = .054 Hypothesis 6: Switching Switching costs only model experience –.31*** –.18* –.27*** Supported Procedural costs .15* .30 Risk aversion .14* .05 .24** — Financial costs .13* Time pressure .17** .01 –.06 — Relational costs .44*** SMC of switching 2 Model fit: χ 1,859 = 3,434, CFI = .97, NFI = .93, p < .000, cost .62 .22 .38 RMSEA = .053 2 Model fit: χ 1,858 = 3,416, CFI = .97, NFI = .93, p < .000, NOTE: SMC = squared multiple correlation; CFI = Comparative Fit In- RMSEA = .053 dex; NFI = Normed Fit Index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. NOTE: Dash (—) indicates that relationship is not hypothesized. SMC = *p < .05, one-tailed. **p < .01, one-tailed. ***p < .001, one-tailed. squared multiple correlation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; NFI = Normed Fit Index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. TABLE 4 *p < .05, one-tailed. **p < .01, one-tailed. ***p < .001, one-tailed. Interaction Structural Models Switching Cost and Chi-Square Satisfaction Interaction Change for DISCUSSION AND Model Constrained Model p Conclusion MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS Hypothesis 9a: Procedural switching cost .70, 1 df p > .10 Not supported The Consumer Switching Cost Typology Hypothesis 9b: Financial switching cost .20, 1 df p > .10 Not supported Hypothesis 9c: This research affords managers a set of tools and a Relational switching cost .70, 1 df p > .10 Not supported framework designed to help conceptualize, measure, and manage consumer switching costs. The eight-facet typology developed in this study provides a granular rep- resentation of consumer switching costs, allowing The Antecedents of Switching Costs researchers and practitioners to more finely distinguish different switching cost elements and to consider their Procedural Switching Costs links with other constructs and practices. The more parsi- Our study suggests that consumers’ perceptions of pro- monious three-factor, higher order switching cost cedural switching costs may be increased by increasing typology addresses researchers, and practitioners need to their perceptions of product complexity or provider heter- conceptualize complex constructs more succinctly. ogeneity; by encouraging broader product use; and by Depending on the demands of the question being pursued, reducing, to the extent possible, their experience with the appropriate level of the typology can be employed. For switching between, and using, other providers. One tactic applied managerial decisions or consumer segmentation, for increasing complexity perceptions is educating con- examination of the specific facets of the eight-facet model sumers about the variety of features a product offers. is more appropriate. For conceptualizing areas for expand- Long-distance and credit card companies regularly send ing switching cost research, the higher order model may be inserts with their monthly bills describing new services more useful.

- 11. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 119 and additional features of the services that they offer. bundled products); by offering loyalty programs; and, as Communications that remind existing customers of the noted above, by informing customers of the variety of features that differentiate their provider from competitors products offered. Adding intangible financial services, may also increase customers’ procedural switching costs, such as credit card purchase insurance and payment insur- reduce their search for alternatives (Heide and Weiss 1995; ance, should increase perceptions of complexity and Weiss and Heide 1993), and reduce their intentions to financial switching costs. Finally, as noted above, a greater switch. emphasis on defensive, over offensive, marketing should decrease the switching experience of a firm’s customers Firms seeking to increase their customers’ switching and increase its financial switching costs over time. costs should also consider bundling products and services. While past bundling research has focused on firms’ ability Relational Switching Costs to maximize sales profits through bundling (e.g., Customers’relational switching costs may be increased Stremersch and Tellis 2002; Venkatesh and Mahajan by increasing their perceptions of provider heterogeneity, 1993), our results suggest that bundling may increase cus- by encouraging broader product use, and by reducing the tomer retainability by increasing the breadth of product alternative provider and switching experience of those use and perceptions of offering complexity. Furthermore, acquired. Suggestions for managing each of these ante- by creatively bundling their products, providers can differ- cedents are offered above. Our results support the long- entiate their offerings and increase customer perceptions standing belief that investments in differentiation of provider heterogeneity. strengthen customers’ bonds of identity with a firm. Fur- Finally, firms seeking to increase switching-cost-based thermore, as customers use more types of a providers’ retention should target customers with limited experience products, they appear to enter a more advanced relation- and avoid avid switchers as they are likely to switch again ship stage in which switching is more costly. Finally, con- in the future. While firms with more sophisticated tools are sumers who have less experience with other providers able to assess the risks and rewards of attracting likely appear to perceive stronger ties to their existing providers. switchers, all firms can take steps to ensure they attract Thus, firms may doubly benefit from discounting cross- those consumers less likely to switch away in the future. sales to existing customers, as they may both increase cur- For example, a survey or interview can be used to assess rent breadth of use and preclude customers’ trial of other the prior history of potential customers, a tactic easily providers’ offerings. employed by services like gyms or clubs. Alternatively, customers can be targeted early in their life cycles, a prac- Satisfaction and Switching Costs tice that credit card companies have honed on teens and as Drivers of Customer Retention college students. When potential customers cannot be sur- veyed or known, firms can de-emphasize customer acqui- Our consequence model confirms that satisfaction sition programs that heavily reward switching. A greater drives consumer intentions to stay with an incumbent ser- emphasis on the basic value proposition and building the vice provider. With satisfaction alone, we explain 16 per- switching cost perceptions of existing customers (e.g., cent of the variance in consumer intentions, well within defensive marketing) should lead to slower but more sus- the bounds reported as typical by Szymanski and Henard’s tainable customer growth. (2001) meta-analysis of satisfaction studies. Thus, we sup- Contrary to expectations, we find a negative relation- port the continued emphasis on managing customer ship between modification and consumers’ procedural satisfaction. switching cost perceptions. Consumers may gain product However, we find that switching costs have an even domain expertise while modifying their products, which stronger effect on customer retention, explaining 30 per- reduces the procedural costs they associate with switching cent of the variance in the consumers’ intentions to stay (Alba and Hutchinson 1987). Alternatively, customers with a current provider. We believe this finding is espe- who perceive lower procedural switching costs may also cially noteworthy given our intentional selection of indus- perceive lower costs associated with making modifica- tries, such as the long-distance industry, that are relatively tions, leading them to make more modifications. Further “fluid”—where perceptions of switching costs exist, but research is needed to better understand this relationship. where they are weak enough that switching is still rela- Financial Switching Costs tively easy. Given the limited research on switching cost Customers’ financial switching cost perceptions may management, it appears that marketing’s pursuit of the be increased by augmenting perceptions of product com- customer satisfaction paradigm has blinded it to the plexity, by encouraging broader product use, and by reduc- importance of switching costs, or worse, that the field has ing the switching experience of those acquired. Firms can “blacklisted” switching costs as customer harming and increase the perceived complexity of their offerings via thus unworthy of study. Yet, even if only “passive loyalty” mixed price bundling (e.g., offering independent and is generated by switching costs, such behavioral constraints

- 12. 120 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 maintain customer satisfaction and that they must regu- can prompt relationship-improving investments by larly monitor switching cost perceptions. The former con- encouraging voice over exit (Ping 1997). In addition, cern suggests that switching costs must be managed with switching costs can inhibit consumers from switching an eye toward customer acquisition. While we have immediately after a dissatisfying incident and thereby cre- emphasized the customer retention applications of our ate the delay needed to return to higher global satisfaction model, our findings are equally relevant for customer levels that were perceived before the incident (Bolton and acquisition management. For example, firms need to Drew 1991). Switching costs, like the commitments of lower potential customers’ perceptions of the complexity marriage, may make for better relationships over time. of their products in order to reduce the costs associated All three switching cost types appear to drive consum- with switching “in.” For years, Microsoft promoted the ers’ intentions to stay with their current provider. Spe- simplicity of its operating systems by emphasizing the cifically, increasing current customers’ perceptions of the “Start” button in its advertising. New customers then gen- risks involved in switching (or the safety of staying), the erated set-up and learning switching costs after they difficulty of evaluating alternatives (or the ease of not installed and used Microsoft’s system. However, Fornell’s doing so), the hassles of setting up a new relationship, and concerns do highlight the potential downside of an the learning required to use a new provider will increase overaggressive use of switching costs. Even if few con- customers’ likelihood of remaining in an existing relation- sumers undertake the hyperrational future switching cost ship. Furthermore, increasing the potential of losing bene- assessments presumed by economists (e.g., Beggs and fits or money (or decreasing the costs of staying—Cannon Klemperer 1992), potential customers may search for and Homburg 2001) will increase customers’likelihood of ways to avoid relationships with firms imposing obviously staying, even when no discernable physical assets are burdensome switching costs (such as lock-in contracts), involved. Finally, increasing the strength of customers’ and existing customers may become dissatisfied and seek psychological bonds with a provider’s brand will increase opportunities to undermine firms that unduly constrict people’s likelihood of staying, even in industries with very them (Jones and Sasser 1995). Thus, switching costs must little or no face-to-face contact. Of the three types, we find be managed judiciously, reducing them for potential new that financial switching costs have the weakest impact— customers and increasing them in ways that add value for our study suggests that procedural and relational costs existing consumers’ experiences. loom larger when consumers consider switching. How- ever, generalizations about the relative strength of the switching cost effects must be made with care. Switching CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH cost effects are likely to vary across industries as contact levels, physically linked assets, solicitation methods, and This research makes three primary contributions to other product and/or market factors vary. marketing research. First, it provides a typology of the We find no evidence for interactions between switching switching costs that consumers perceive as well as vali- costs and satisfaction. This suggests that switching costs dated scales for measuring those costs. We find consistent remain a valuable tool for fighting the surprisingly preva- evidence for eight distinct consumer switching costs: eco- lent loss of satisfied customers (Jones and Sasser 1995). nomic risk costs, evaluation costs, learning costs, set-up Clearly, firms have strong incentives to ensure that both costs, benefit loss costs, monetary loss costs, personal- satisfaction and switching cost management are well relationship loss costs, and brand relationship loss costs. tended. In addition, both ethical and practical consider- These eight switching costs comprise three higher order ations suggest that firms should seek to increase switching switching cost types: procedural, financial, and relational costs in ways that add value to consumers. By helping cus- switching costs. Given the breadth of the literature from tomers learn how to better use the product, by identifying which the typology is drawn, its consistency across the unique features offered, by offering valuable bonus points industries studied, and its parsimonious nature, we believe or loyalty services, and by engaging customers in a more that the typology should provide a solid foundation for meaningful relationship, firms should seek to simulta- conceptualizing the nature of switching costs for con- neously raise customer switching costs and improve cus- sumer products (goods and services). We encourage future tomer satisfaction. research employing our scales to build on our understand- In managing consumers’ perceived switching costs, ing by exploring its application in new contexts. While the strategists are reminded of two potential problems associ- scales may need to be adapted to suit specific contexts, ated with relying on barriers to exit (Fornell 1992): (1) cus- perceptions of the three major switching cost types should tomer awareness of switching costs may impede customer be found whenever switching is clearly defined. It is acquisition, and (2) switching costs may be neutralized or important to note, however, that with many products (and eliminated by external forces. The latter concern merely especially discontinuous products), consumers can try suggests that firms should not drop their efforts to new offerings without fully switching to them. When this

- 13. Burnham et al. / CONSUMER SWITCHING COSTS 121 is the case, some of the costs associated with using a new moderators of the relationships studied will enhance the offering will be lower or nonexistent, and the term switch- managerial application of switching costs. For example, ing costs may be inappropriate. It is left to future research- the effects of breadth of product use may depend on the ers to fully distinguish the appropriate contexts for using complementarities between the products purchased from a the terms switching costs, adoption costs, and trial costs single provider and on the physical compatibility between and to identify any differences in the types of costs per- assets used with different providers. Similarly, the effects ceived in each context. of prior experiences may depend on the valence of a con- Second, this research provides a theoretical framework sumer’s experiences with other providers and the switch- of the antecedents that drive consumer switching cost per- ing process and even on the consumer’s switching experi- ceptions. We find that three categories of antecedents— ences in contexts outside of the focal product domain. A market characteristics, consumer investments, and domain longitudinal study could offer insights into how switching expertise—can significantly influence the switching costs cost perceptions, switching experiences, and (behavioral) that consumers perceive. These findings concord with, and loyalty change and affect each other over time. In addition, expand upon, prior switching cost antecedent research switching costs’ effects on intentions to stay may depend (e.g., Alba and Hutchinson 1987; Jackson 1985; on the context in which switching is considered; receiving Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988) and provide managers a financial offer from a competitor may make salient dif- with a broad theoretical basis for designing specific ferent switching costs than enduring a problem with an switching cost management programs. existing provider. Switching costs’ effects may also Third, this research adds to recent research on switch- depend on such industry characteristics as product usage ing cost consequences (e.g., Bansal and Taylor 1999; and solicitation norms. Finally, research on the relation- Jones et al. 2000) by finding significant effects for three ship between switching costs and satisfaction could assess types of consumer switching costs. Even within industries whether, or when, switching costs lead to dissatisfaction. where objective switching costs are low, we find that the While both self-perception theory and cognitive disso- level and types of costs that consumers associate with nance theory suggest that consumers who are “stuck” in a switching explain their intentions better than their satisfac- behavior will defend the behavior and view themselves as tion does. While this does not suggest that firms should satisfied, a dissatisfied customer who can attribute being abandon the pursuit of customer satisfaction, it does high- stuck to a firm’s actions will certainly feel even more dis- light the need to understand, measure, and manage switch- satisfied. But can switching costs independently lead to ing cost perceptions. dissatisfaction? Studies providing answers to such ques- Many interesting switching cost management ques- tions will extend our ability to manage the dynamic, con- tions await future researchers. Additional research on the textual effects of consumer switching costs.

- 14. 122 JOURNAL OF THE ACADEMY OF MARKETING SCIENCE SPRING 2003 APPENDIX TABLE A1 Switching Cost Scale Items, Loadings, Reliabilities, Means, and Standard Deviations Standardized Item Loading Coefficient Alpha Mean Standard Deviation Long- Credit Long- Credit Long- Credit Long- Credit Scale Distance Card Distance Card Distance Card Distance Card Economic Risk Costs .85 .87 3.37 3.02 0.81 0.94 I worry that the service offered by other service providers won’t work as well as expected. .72 .69 If I try to switch service providers, I might end up with bad service for a while. .60 .72 Switching to a new service provider will probably involve hidden costs/charges. .75 .73 I am likely to end up with a bad deal financially if I switch to a new service provider. .74 .72 Switching to a new service provider will probably result in some unexpected hassle. .74 .78 I don’t know what I’ll end up having to deal with while switching to a new service provider. .70 .80 Evaluation Costs .80 .83 3.55 3.26 0.84 0.98 I cannot afford the time to get the information to fully evaluate other service providers. .68 .79 How much time/effort does it take to get the information you need to feel comfortable evaluating new service providers? (very little . . . a lot) .65 .72 Comparing the benefits of my service provider with the benefits of other service providers takes too much time/effort, even when I have the information. .66 .69 It is tough to compare the other service providers. .87 .78 Learning Costs .85 .85 2.93 2.88 0.91 0.94 Learning to use the features offered by a new service provider as well as I use my service would take time. .68 .78 There is not much involved in understanding a new service provider well. (r) .77 .69 Even after switching, it would take effort to “get up to speed” with a new service. .79 .81 Getting used to how another service provider works would be easy. (r) .84 .79 Set-Up Costs .74 .80 3.13 3.04 0.85 0.97 It takes time to go through the steps of switching to a new service provider. .64 .67 Switching service providers involves an unpleasant sales process. .61 .80 The process of starting up with a new service is quick/easy. (r) .70 .77 There are a lot of formalities involved in switching to a new service provider. .68 .79 Benefit Loss Costs .81 .76 2.50 2.84 1.15 1.28 Switching to a new service provider would mean losing or replacing points, credits, services, and so on that I have accumulated with my service provider. .74 .71 How much would you lose in credits, accumulated points, services you have already paid for, and so on if you switched to a new service provider? (lose nothing . . . lose a lot) .89 .90 I will lose benefits of being a long-term customer if I leave my service provider. .70 .58 Monetary Loss Costs .72 .71 2.58 2.41 0.98 1.01 Switching to a new service provider would involve some up-front costs (set-up fees, membership fees, deposits, etc.). .68 .67