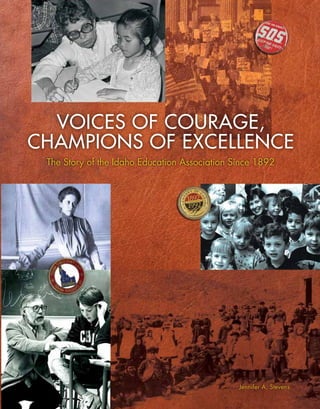

The Story of the Idaho Education Association Since 1892

- 1. Voices of Courage, Champions of Excellence VoicesofCourage,ChampionsofExcellenceTheStoryoftheIdahoEducationAssociationSince1892 The Story of the Idaho Education Association Since 1892 T he Idaho Education Association was founded on March 3, 1892, and quickly established itself as the leading advocacy organization for public education in Idaho. During its 120 years of championing universal, tuition-free, quality public education for Idaho’s children, the Association has made great strides. It has lobbied for high student and teacher standards, embraced innovation in the classroom, won fair workplace rights for educators, and been the foremost voice for adequate and equitable state funding. Voices of Courage, Champions of Excellence tells the story of the brave educators who, on behalf of their students and their profession, confronted powerful policymakers, partnered with parents and other education supporters, and spoke loudly at the capitol and in the voting booth so Idaho’s children could have the best chance possible to become productive, educated citizens with a stake in our state’s and our country’s success. The Idaho Education Association’s: – Mission Statement (adopted in 1995) The Idaho Education Association advocates the professional and personal well-being of its members and the vision of excellence in public education, the foundation of the future. – Focus Statement (2000) To help local associations build capacity to achieve excellence in public education. – Core Values (2004) Public Education: Preserving the foundation of our democracy. Justice: Upholding fair and equitable treatment for all. Unity: Standing together for our common cause. Integrity: Stating what we believe and living up to it. $10.00 Jennifer A. Stevens First school in Mountain Home.

- 2. 1 Voices of Courage, Champions of Excellence The Story of the Idaho Education Association Since 1892 Jennifer A. Stevens

- 3. 2 ISBN 10: 1-59152-102-5 ISBN 13: 978-1-59152-102-0 ©2012 by Idaho Education Association Text © 2012 by Jennifer Stevens Cover and interior design by: Don Gura Graphic Design, Inc. Copy editing: Neysa CM Jensen. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part by any means (with the exception of short quotes for the purpose of review) without the permission of the publisher.

- 4. 3 Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Bibliographic Note . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 Chapter 1: 1892-1926 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Beginnings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Getting Settled: The First 25 Years . . . . . . 9 Teachers as Role Models and the Students’ Moral Compass . . . . . . . . 10 The Profession . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 The IEA’s Organizational Evolution . . . . . 14 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 Schools Then and Now: Lowell Elementary, Boise . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20 IEA and the NEA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Chapter 2: 1926-1940 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Fighting For Idaho’s Children During Tough Times . . . . . . . . 24 The Depression and the Impact on Educational Funding . . . . . . . . . . . 26 Idaho’s Endowment Fund . . . . . . . . . . 27 State Funding for Education and Equalization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 Rural Schools: Consolidation and Teacher Training . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 Chapter 3: 1940-1963 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Keep the Teachers Here! . . . . . . . . . . . 36 Circling ‘round: Educational Funding and the Sales Tax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45 Technology and Schools . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 IEA Headquarters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48 Chapter 4: 1963-1980 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Money, Politics, and Education in Idaho . . . 51 Giving Teachers Security and a Voice: Retirement and Professional Negotiations . . 57 Change in the Local Associations and the Structure of the IEA . . . . . . . . . . . 60 UniServ: Empowering, Organizing, and Representing Members . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 The First 1% Initiative . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 Idaho Teachers’ Strikes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65 Chapter 5: 1980-2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 Creating a Fair Workplace . . . . . . . . . . 66 Politics and Competition in Education . . . . 70 Voluntary Contributions Act . . . . . . . . . 74 IEA and Community Work . . . . . . . . . . 75 The IEA Children’s Fund . . . . . . . . . . . 76 Education Support Professionals . . . . . . . 77 Idaho Education in the 21st Century . . . . . 77 A Penny for Schools . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82 Three Years of Cuts to Education, 2009-2011 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84 Historic Alteration of School Laws Headed for Referendum . . . . . . . . . . . 85 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86 Teacher Compensation: istars vs. weteach . 87 Barbara Morgan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88 The Continued Professional Improvement of Idaho Teachers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92 Appendix A: Listing of all IEA Presidents . . . . 94 Appendix B: Listing of all IEA Executive Directors . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96 About the Author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97 Historic Photos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98 Contents

- 5. 4 Acknowledgements The Idaho Education Association created a History Project Task Force made up of longtime IEA members and staff from across the state. The Task Force was created to capture, record, and publish the 120-year history of the Idaho Education Association. Without them, this book would not be in your hands. Members include: Dale Baerlocher, Marcia Banta, Charlotte Cooke, Sue Finlay-Clark, Terry Gilbert, Judy Harold, Sue Hovey, Danial McCarty, Rob Nicholson, Peggy Park, Kathy Phelan, Dan Sakota, Willie Sullivan, and Kathy Yamamoto. A smaller group within the Task Force took on the detailed management of the project, and the book could not have been completed without their passion, good humor, research, and other hard work. This group was composed of Sherri Wood, Jim Shackelford, Lyn Haun, Gayle Moore, and Bob Otten. All are former teachers, and their passion for the Idaho Education Association and the children it serves is evident in everything they do. They entrusted me with the management of the project and more importantly, with the telling of their story, an awesome task to which I hope I’ve done justice. The Association President, Penni Cyr, its Executive Director, Robin Nettinga, and the IEA Board of Directors all have been instrumental to the project as well, lending us their enthusiasm and their funding support. Without them, the project could not have reached completion. Special thanks also go to the many staff and volunteers of the Idaho Education Association who have contributed to the organization over the past 120 years, making it the advocacy group it is today. I also want to thank Kelly Horn, who attended public schools in southeast Idaho and is a newly-minted M.A. in History from Boise State University. She provided invaluable assistance on this book and wrote some of the interesting side stories you will read throughout. Finally, the book is dedicated to all of Idaho’s teachers who arrive at school each day with a mission to mold tomorrow’s citizens into people who are engaged, impassioned, and equipped with the skills they need to make our country a better place. Their dedication to our children is a debt that is impossible to repay. — Jennifer Stevens Bibliographic Note The story on the following pages was written by examining the records of the Idaho Education Association. It is intended to be a history of the group’s advocacy work and passion for educating Idaho’s children. Any reader who wishes to find out more about the sources used can contact the author, Jennifer Stevens, at jenniferstevens@shraboise.com. All photographs of schools, teachers, and students were taken in Idaho.

- 6. 5 Those who make history rarely understand the significance of their actions at the time. Such was surely the circumstance when Idaho’s educational leaders founded the Idaho State Teachers’ Association on March 3, 1892. g From its founding, the ISTA, or Idaho Education Association as it is known today, grappled with the many complicated issues facing the education of Idaho’s youth. g The IEA is Idaho’s professional organization for educators and, as such, has led the state through its long educational evolution from an inefficient system of myriad rural schoolhouses staffed by poorly trained, inadequately equipped, and dismally paid teachers to a system organized by districts in which resources are shared across schools and children and families can count on well-trained and highly qualified teachers. g Over the years, the IEA has provided the platform for educational debate and led the charge for an improved educational investment. g Although their courageous activism often resulted in criticism from the general public, IEA members championed excellence in public education and brought Idaho out of the dark days of the 1970s when it was first discovered that the state ranked 50th of all states in educational investment. g Although Idaho’s ranking remains close to the bottom, the IEA has taken many steps to provide Idaho’s children with an excellent education in spite of the funding challenges. g During the IEA’s 120 years, historical circumstances have provoked statewide debates over curriculum changes, technological evolution, the place of patriotism in education, teachers’ rights, the role of schools in communities, and qualification of and employment protections for teachers. g As an intensely democratic organization from its 19th century founding, the IEA has advocated for increasingly high levels of qualification for educators, pushing them to become better teachers and administrators. g No matter the winds of change, the Idaho Education Association has maintained its fundamental focus: fighting for high quality and equal educational opportunities for all of Idaho’s children, whether special needs, gifted, blind or deaf, or minority. g This book tells the story of the battles fought, details the victories accomplished, and anticipates the challenges ahead. Introduction o

- 7. 6 T he attendees at the first Idaho State Teachers’ Association Convention arrived in Boise by train in early spring 1892, bustling with excitement about the new professional organization they were here to join. They came with curricular ideas for the children they taught and creative methods to share their knowledge with colleagues. Educational leaders in this new western state had decided only three weeks earlier that there was a need for a statewide organization dedicated to ensuring Idaho’s children received the best education the United States could offer. State Superintendent of Public Education, Judge J. E. Harroun, called a meeting in his office on March 3, 1892, to discuss the issue with four county superintendents and, together, they called for the establishment of a permanent state teachers’ association. That day, they hatched the idea for what is now the Idaho Education Association. 1892-1926 Chapter 1 o The early years of the Idaho State Teachers’ Association are replete with stories of hope, innovation, and passion. g The events of these first few decades set the stage for the many years to come. g The group gradually evolved from an organization of impassioned teachers who cared deeply about improving the educational opportunities for children across the state of Idaho to a group of members who took concrete actions to ensure that those opportunities were available. g From debates over curriculum and teacher certification and standards, members of the Association demonstrated to Idaho’s policymakers that their classroom knowledge and expertise about children’s needs were assets. g The organization proved to be savvy about budget and organizational matters as well, advising and sometimes lobbying the state on matters related to funding public education and how to classify and organize the many schools throughout Idaho. g The Association recognized that it could offer information and data on elementary, middle and high schools, as well as the particular challenges associated with rural schools. g Throughout this time, members focused heavily on the role of the teacher, forming a consensus that the teacher should educate students of all ages about good citizenship and serve as upstanding moral citizens themselves. g As time passed and teachers became more consistently trained, the profession matured tremendously and became one of which Idahoans could be proud and to which they owed much. Beginnings

- 8. 7 Teacher and students at tent school, location unknown The atmosphere in the capital city just three weeks later was gay indeed. Harroun and his collaborators had called for the state convention of teachers and other educators to begin in Boise on March 22. Arriving in town on specially negotiated train fares, teachers gathered at the state capitol to implement Harroun’s plans and make the creation of a professional organization a reality. Governor Norman B. Willey and Boise Mayor J.A. Pinney both arrived at the gathering to speak to attendees, whose numbers were small but enthusiastic. Idaho’s promise was palpable, with its ample natural resources and growing population in a state that was less than two years old. Railroads were being extended into and throughout the state, connecting the remote and landlocked area with the rest of the West and the bustling nation. Irrigators were starting successful enterprises in the Boise Valley and across the southern half of the arid state, and with those businesses came people and families with children. Willey spoke to the attendees about the children’s needs and about the defects of existing school laws in Idaho. To demonstrate the greatness of Idaho’s educational system, and to correct the Eastern idea that “the children of this great west are well-meaning savages,” the teachers, principals, and superintendents in attendance talked at length about the educational exhibit they would display at the World’s Fair, to be held the following year in Chicago. And most importantly, between the soprano solos and social intercourse, Superintendent Harroun appointed a five-member committee to determine the next steps toward a permanent organization. Before the convention’s conclusion, the committee’s three women and five men proposed a constitution for the newly created State Teachers’ Association of Idaho.

- 9. 8 From these humble beginnings in March 1892, the Idaho State Teachers’ Association’s (ISTA) adopted constitution made clear that the mission of the organization was “to promote the educational interests of the state, and to further insure the future progress of the teachers’ work as a profession.” Leaders believed that professionalizing education was the key to ensuring universal quality free public education for all of Idaho’s youth. But the goal of professionalization provoked many controversial battles during the ensuing 120 years. The 1892 convention saw the first organization-level discussions about many of the issues that teachers continually fought for during the 20th century: fair and competitive salaries and workplace conditions for teachers; increased standards and qualifications for teachers and administrators; equality of education for children no matter the wealth of their community. The ISTA believed that without highly qualified teachers who were drawn to the state because of the competitive salaries and benefits, the education of Idaho’s children would continue to operate with a frontier mentality. Patriotic to their core, members of the ISTA also intended the organization to be a democratic institution from the start, providing each county in the state with a representative and setting a reasonable and affordable dues schedule of $1 annually per person. They also adopted a manner of working through committees, where members would be represented and policies could be recommended to the larger body. Early committees included the constitutionally created executive and legislative committees, comprised of three and five members, respectively, with the first intended to arrange annual meetings and the second directed to “use their influence securing needed legislation such as they or this association may deem necessary for the best interests of the state.” Legislative work was deemed necessary as a tool for ensuring that Idaho’s children were being provided the best education possible, although some came to believe that schools and politics were better left apart. The Committee on Resolutions was a policy body, and the first convention’s members voted to recommend higher standards in the granting of teaching certificates and the creation of a teacher training school — known as a normal school — in Idaho. The same committee recognized and expressed disapproval of efforts by school boards throughout the state who were trying to reduce teachers’ salaries. Therefore, the committee urged educators to refuse to accept lower salaries than their predecessor when taking a new position in the state. The committee structure was a fluid one which evolved continuously as the organization faced new and challenging issues over the years. Teacher and students at wooden school, location unknown Meanwhile, buzz over the first ISTA convention had grown throughout the week, with the Idaho Daily Statesman covering each day’s proceedings and praising the educators’ organization.

- 10. 9 Meanwhile, buzz over the first ISTA convention had grown throughout the week, with the Idaho Daily Statesman covering each day’s proceedings and praising the educators’ organization. Before concluding, the convention featured discussion and debate over what to teach in school, setting the stage for what would become one of the most important and long-standing functions of the organization: a platform for expressing and debating the evolving vision for education. New member teacher Miss Newton explained in her presentation that in addition to basics such as reading and math, producing moral, upstanding citizens was the goal of education. The goal of teaching morals and character to students continued to be an important one well into the 21st century, although methods remain controversial even today. Closing its three-day meeting on March 25 and setting a time to meet again in April the following year, the group accepted an invitation from the Rapid Transit Company to ride its electric cars on an excursion to the Natatorium for a swim and a party. The celebration was no doubt lively, as teachers, principals, and administrators rejoiced over education’s new beginning in Idaho. Getting Settled: the First 25 Years Following the successful first meeting, leaders in the Idaho State Teachers’ Association spent the next 25 years formalizing the organization, making efforts to reach educators across the state, and taking major strides toward professionalization. As the Association’s membership grew, the group began to reach out to the National Education Association as well as to other state’s education organizations to form closer alliances. However, it also began to recognize that its members had many varied interests that could not all be addressed in a large group setting. Primary school teachers, high school teachers, and administrators had very different everyday concerns, and the organization of the association gradually evolved to reflect those issues. The ISTA achieved the necessary flexibility in its organizational model while also working toward providing educators a voice in general policies that affected their classrooms every day, such as textbook selection, curriculum design, and content. Over the next few years, teachers who attended the annual meetings overflowed with ideas and visions for education for Idaho’s children. As the Teachers’ Association moved its annual meeting to different parts of the state each year, it became common to feature a discussion of meatier issues related to teaching and the classroom. These meetings offered a platform where open debates could be held about the ideal teacher (and how moral he or she should be), what constituted a high school, how to teach reading, the role of music and art in the classroom, geography, civics, and the value of nature study. Participants discussed language instruction in the intermediate grades, methods of teaching, and the need for Roswell School, date unknown

- 11. 10 physical education. In December 1893, the Association appointed a committee to organize a State Reading Circle that could recommend “proper” books to be read across the state. The Reading Circle Board was formalized via ISTA Constitutional amendments in 1900 and charged with planning curricula related to pedagogy as well as culture. The ISTA wanted to create a streamlined education across the state, for teachers as well as for students. Teachers as Role Models and the Students’ Moral Compass With regard to cultural issues, one of Idaho educators’ early concerns — and one that lasted for many decades — was that students receive moral guidance at school. This mandate required teachers to both act as a moral compass for their students and also teach their students about morality. At the time the State Teachers’ Association was founded in 1892, the country was steeped in Victorian purity and engaged in a lengthy and heated debate over temperance and the evil of drink. Perhaps inevitably, then, these moral issues crept into debates about education in Idaho. Some of the greatest leaders of the temperance movement were women, and, coincidentally, women also made up a high proportion of the teaching profession. In 1894, the ISTA’s annual meeting featured a systematic report of teachers’ work and a “stronger conviction of the value of moral and religious instruction as essential elements of the education of our youth.” Along these lines, that year’s Committee on Resolutions resolved that: “the development of the personal character of the pupils and the formation of habit in all right directions is the supreme function of the teachers. For this reason we hold that teachers should be the embodiment of those virtues that characterize the highest types of manhood and womanhood and we deprecate any conduct or habit that detracts from the dignity of the teachers as such, or as an exemplar of precepts of true morality.” Other papers urged teachers to do “earnest and self denying work,” and to uphold higher standards and morals, including no tobacco, no intoxicating drinks, no turkey shooting, no attending baseball on Sundays, and no other reprehensible activities. According to the leaders at the time, true role models would not engage in such things. In addition to acting as role models, the ISTA wanted educators to teach those same morals. As the ISTA continued to grow in influence into the 20th century, it recommended laws that would assist in implementing character education. In 1907, the Association recommended that state law be altered to mandate teaching the Bible in public school, and members even discussed changing the State Constitution to this effect. Such a law did not come to fruition, but the Resolutions Committee decided that, at the minimum, “non-sectarian religious instruction should not be prohibited in the public schools of Idaho.” Thus, from very early on, there was great concern with making “good American citizens,” and teachers were expected to be among the best role models available. “…the development of the personal character of the pupils and the formation of habit in all right directions is the supreme function of the teachers. For this reason we hold that teachers should be the embodiment of those virtues that characterize the highest types of manhood and womanhood and we deprecate any conduct or habit that detracts from the dignity of the teachers as such, or as an exemplar of precepts of true morality.” — Committee on Resolutions, 1894

- 12. 11 1896, Kellogg School Good American citizens were also expected to be patriotic, and the Association focused on teaching patriotism as early as 1894. Creating good, productive citizens was a goal of the State Teachers’ Association from the start, and over the course of the Association’s 120 years, the country went through many periods when patriotism in the schools was emphasized. When discussing proper books to assign in 1894, teachers complained that the readers currently in use were unacceptable because they did not “contain selections that tend to teach patriotism.” Another teacher retorted: “We should be capable to teach patriotism without a book as morals without the Bible.” But clearly, the debate was not over whether to teach patriotism, but how. Teaching civics was presented as one solution. Teachers declared that the “perilous time” of “class jealousy, distrust and conflict” in which they were living had resulted in a large percentage of citizens who were uninformed about the “sacredness” of governmental authority. They resolved that teaching civics would help smooth such divisions, and with “every man and woman… well versed in all that pertains to civil government,” the country would be safer. Wartime regularly brought this issue to the fore for educators in Idaho. As tensions with Spain heated up in anticipation of what would become the Spanish American War in April 1898, the ISTA’s Committee on Resolutions recommended, and the full membership passed, a resolution in late 1897 requiring all

- 13. 12 educators in Idaho to fly “Old Glory” over every school house and inculcate patriotism. Some years later, when relations in Europe were strained and eventually led to World War I and the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, Idaho educators were intent on teaching students about the “meaning” of Americanism. In 1918, that meant ISTA support for the Americanization Act, a bill that would require all residents of Idaho to attain a fifth grade proficiency in English. And in 1919-1920, at the height of the country’s first Red Scare, the ISTA’s Resolutions Committee recommended a pledge of loyalty to “sane Americanism” and urged teachers to recognize the importance of their efforts in guiding students through “those principles of Americanism which have made and which will keep us a free people.” Around the same time, Kellogg’s superintendent, working in a highly charged atmosphere caused by labor unrest in north Idaho, designed an Americanism curriculum that required students in grades 1-8 to learn the Pledge of Allegiance, the flag salute, and many patriotic poems and songs. Upper grade-school children were required to write a story explaining what it meant to be a “real American.” Such pleas for patriotic instruction dominated discussions about classroom content for many years and were especially overt during times of war. The Profession The early years of the ISTA also featured critical debates over teacher qualification and teacher training. Expecting the best from their members became commonplace in the organization. When the ISTA’s fourth convention was held in Moscow in late 1894, qualifying to be a teacher required only that a person be 16 years of age or older and pass an examination by the county superintendent. There were no consistent standards for such examinations, and teaching certificates were passed out rather freely. Our children, exclaimed one convention attendee in 1894, “are protected from quack doctors but not quack teachers!” Teachers in the Association blamed the lack of qualifications for failures in teaching, and the members of the ISTA launched a 100-year fight for more formalized training and higher qualifications as one solution to the problem. The 1894 convention began with a discussion about the issuance of permits, all agreeing that more training and experience were necessary. Compared to other states, Idaho had low expectations for its teachers’ education. The ISTA favored more professional training, even for existing members, and was thrilled with the legislature’s creation in 1893 of two normal schools designed to train teachers in Idaho. While normal school education was a good start, most agreed that it did not automatically qualify a person as a good teacher. So the ISTA — and later, the IEA — spent many 1895, Sublett School

- 14. 13 years trying to raise the bar so students would have the best teachers available. The goal of improved standards was not meant to erect a barrier to those entering the profession but to ensure that those who chose teaching as a career would be the best people to educate students. ISTA members wanted to create requirements so that teaching never became a fallback or temporary profession, but rather, a cherished career. To accomplish the goal of more qualified teachers, the ISTA’s first printed legislative program, in 1898, included the organization’s successful demand that both the Lewiston and Albion normal schools be placed under a single state board that could make the programs more consistent and rigorous. The ISTA lobbied for additional changes to Idaho educator training and qualification as well, including a minimum age of 30 for the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. By the end of this early period, the ISTA was recommending further requirements with the backing of the state superintendent, Ethel Redfield. Redfield addressed the 1919 annual convention and argued that certification standards needed renewed improvement. Almost all surrounding states had passed laws requiring four-year degrees for teaching in the high schools, and she recommended that Idaho do the same. She and the ISTA lobbied for laws that would require teachers with only a normal school education (aimed specifically at teaching) and no bachelor’s degree be confined to the elementary schools. Those with four- year university degrees but no special training in early childhood education should be steered toward teaching the upper grades and kept out of the lower schools without special preparation. Salaries were also a subject of debate for members of the ISTA. Competitive wages were viewed as a tool for attracting the best teachers and therefore providing students with the best education. Some gains were made early on in the Association’s history. And, despite public fears about teachers joining the larger labor movement and becoming “radical” in the second decade of the 20th century, educators debated the salary issue without threat of striking. ISTA President J.J. Rae spoke freely of the salary question in 1919, hoping the legislature would set a salary schedule that would make wages consistent from district to district and county to county. Explaining the discrepancy between teachers with the lowest level certificate receiving $100 monthly while some normal school graduates received only $90, Rae strongly urged legislative action. A major shortage of teachers in Idaho around this same time caused the organization to examine potential causes. The Committee on Professional Standards and Progress issued a report in 1920 on Idaho teacher statistics such as median ages, gender distribution, educational backgrounds, and average salaries. The “Report of the Investigation on the Teacher Shortage in Idaho” stated that there were 4,800 teachers in Idaho and identified eight prime causes of unrest among educators, including insufficient salaries, poor buildings and equipment, indefinite contracts, unpleasant social and living conditions, lack of social advantages, poor community relations, lack of institutional and professional advantages, an “absence of state consciousness,” and lack of cooperation with the state institutions in 1902, Lost River School

- 15. 14 meeting the shortage fairly. The report called for higher salaries and better school buildings, and it urged teachers to educate the public about problems in education. Although Idaho teachers — restless or not — never did affiliate with the larger labor movement of that era, they did begin to forge stronger relations with the National Education Association in the early 1920s as a way to establish solidarity in the profession. Members of the ISTA began to serve at the national level and attend national conventions, then returned to their state organization convinced that the NEA could unify the legitimate needs of teachers nationwide. They recommended that Idaho teachers become members of the national organization, and they urged the state association to affiliate with the NEA, a relationship that was formally created in 1920. Salaries, standards, and the national organization would remain issues of concern for the ISTA in the years to come. The IEA’s Organizational Evolution While working toward major changes in standards for teachers and the other key educational issues, the organization itself had to grow and evolve to meet Idaho children’s needs. By 1896, the ISTA recognized that the increasing number of attendees at its annual gatherings translated into public approval and credibility. While the teachers still desired “more complete professional preparation,” they were pleased with the educational advancements that had been made in the state and turned to curricular concerns and organizational issues in expanding their mission. To execute on this, the 1896 convention sanctioned a five-person committee to revise the constitution for discussion at the next annual gathering. Constitutional revision took a number of years. Small changes were made, but in 1900, members voted to draft an entirely new constitution. By the time the 15th annual meeting in 1905 rolled around, the ISTA had divided its members into sections so that educators could attend sessions relevant to their daily lives in the classroom. The Primary Section, Grammar Section, and High School Section each presented papers that dealt with topics of concern for teachers in those grades. For instance, the Primary Section, which boasted 70 attendees in 1905, discussed issues relating to teaching character and studying child development. The Grammar Section, made up of members who routinely taught intermediate-age children, discussed methods of teaching history and geography. The High School Section discussed “the problem with high school boys” and issues such as teaching science and history in high schools. In addition to meeting in sections, General Sessions allowed members of each group to meet and discuss issues relevant to all educators.East Side School, Idaho Falls area, date unknown

- 16. 15 This method of division continued for many years, and additional sections were added over time. In a move that reflected the politics of the day but also foreshadowed the divisions of the future, administrators created a Superintendents’ and Principals’ Section in 1907. Although collaboration between administrators and classroom teachers continued for some time, the move was a clear indication of the divergent interests of teachers and administrators. Perhaps to ease the transition and the split, the administrators did request that their section meet separately (instead of simultaneously) from the High School Section in the future, so that they could continue to benefit from attending the teachers’ sessions. While classroom teachers in all sections spent most of their meeting time at the annual conventions discussing content matter, the superintendents’ sessions focused on issues such as medical inspections in the schools (this was a major concern because of the growing understanding about the spread of communicable diseases) and educational funding legislation. The superintendents agreed in 1907 to appoint a committee to study and draft resolutions related to this point. In addition to the Superintendents’ Section, a Rural Section was created around 1910, geared toward studying and improving rural education. Rural school life in Idaho had been a subject of concern for the ISTA since its founding in 1892. Because the vast majority of Idaho was rural at the time, and remained so for many decades to come, the ISTA felt an overwhelming obligation to serve these students with an education equal to that offered in more urban areas. Rural schools were dominated by one-room school houses in remote locations where teachers were often inexperienced, young, and required to be janitor, babysitter, woodcutter, and teacher all at once, leaving students underserved. In addition, many rural children spent the majority of their time working — whether on family farms, mines, or other manual jobs — instead of in school. There was a definite zeal for lifting these children out of educational darkness. In 1894, the organization declared the “rural school problem” to be one in which a student was unable to “think by himself and for himself,” and members worried that rural students did not know how to think “accurately” or how to pursue good literature, a love of nature, or knowledge of our government. The ISTA deemed the solution to the problem to be “obedience to moral and civil law, through being led into a love for the freedom under them” and lobbied for a longer school year to help rural children. Yet, there was also a strong desire to keep families on farms. The tension between the desire to maintain a nation of farmers and the simultaneous hope to improve educational opportunities often worked at odds in the state of Idaho. While members of the ISTA yearned to bring education to rural areas, Idahoans’ genuine desire to eschew urban life and help maintain America’s heritage as an agricultural nation meant rural education would be a subject of great debate. In the 1890s, farmers nationwide experienced a severe agricultural depression, and Idaho farmers were not spared. The ISTA went on record regarding the importance of educated 1902, Kootenai County teachers

- 17. 16 Shoshone School, date unknown

- 18. 17 farmers, making education affordable for them, yet still encouraging those educated in agriculture to return to the farm. Concerns over rural and agricultural education began to dominate the annual meetings by 1909. In particular, apprehension remained that children were leaving the country and heading to town for schooling because of the poor nature of rural schools. The desire to maintain a robust country population inspired the ISTA’s Rural Section to tackle issues related to the rural school’s significance to the community as well as the social importance of the country school. By 1910, the full membership agreed to appoint a legislative committee to study the problem and to lobby for laws that would change the distribution of county funds based on school population; allow high schools in incorporated towns and cities to create union high school districts (by merging multiple independent districts); and provide state funding to each school with a teacher fully employed in high school work. That year, the Association went on the record in favor of agricultural education, which would provide a formal vocational education for farmers intending to return to the land, and in 1915, thanks to the ISTA, the Idaho Legislature extended the minimum school year to seven months. Thus, the early 20th century was critical for the ISTA’s work on behalf of rural Idaho children. The ISTA’s Rural Section was not the only one to deal with fundamental issues. The High School Section provided an equally vigorous forum for determining the vision for high school education in Idaho. At a time when only a small percentage of students continued past high school to obtain a university education, there was much debate over the intent of high school education and what it should offer. Should it be steeped in classics, or should it also offer vocational training? These questions were being debated nationally, as well, as high schools began to serve a larger and more varied student population, many of whom had goals other than attending college. At the turn of the 20th century, the ISTA’s High School Classification Committee — which preceded the High School Section — focused on accrediting high schools so that universities would have a system by which to judge the students who emerged from them. The committee recommended that there be opportunities to attend high school for a period of one to four years. Two courses of study were recommended for the four year high school course: one was designed to prepare students for university study in science, the other for university study in humanities. The curriculum for each of these was almost identical, with five 40-minute periods per week of math, English, and history and government. However, the science course then included another five periods of science, while the humanities course included five more periods of Latin study. Just a few years later in 1904, the ISTA lobbied for free public high schools for all students. Because the high schools previously had served only a small percentage of the population, they had required tuition payments by students. Thus, in addition to spurring debate over a high school vision, the Association oversaw the implementation of this vision across the state and was critical in making it available to any student who desired the education. From this point forward, the widespread opportunity to obtain a classical education beyond age 14 differentiated American education from European education throughout much of the 20th century. More organizational changes were on the way for the ISTA. In 1919, the Association established five committees at its annual meeting to deal with long-standing concerns for the professional organization. The Committee on Teacher Shortage would

- 19. 18 determine how to make the profession more attractive, what constituted a living salary for teachers, and how positions could be made more permanent. The Committee on Professional Standards and Professional Progress was charged with developing standards for the profession of teaching. The Committee on Educational Publicity would run the newly approved newsletter, The Idaho Teacher. The Legislative Committee would consider proposals for legislation and report on progress that could be achieved by legislation. The Budget Committee would steer the Association’s finances. The committees were charged with preparing reports in anticipation of the annual meeting, publishing them in the newsletter, and awaiting the votes of the Delegate Assembly. The refined committee structure did not solve all of the problems associated with a growing organization. They needed staff. Finally, in 1925, the ISTA voted to employ an executive secretary, establish permanent headquarters in Boise, and reorganize on a more “effective” basis. In these early years, the ISTA existed rent-free in a room at the Capitol Building, moving to Room 331 in the Sonna Building on Main Street when the legislature arrived every other year. The middle years of the 20th century would see the organization grow to occupy even more space. Conclusion In addition to the usual standing concerns, some issues that seemed minor in these early years became much bigger debates in later years. Among these were maximum class size (recommending a maximum of 40 students for the lower grades in 1903), higher salaries, equal school funding (through a minimum county levy), and school lunches (1910). Politically, the organization got involved by lobbying for legislation that would further their aim of a streamlined, free public education for all children in Idaho. Part of that effort involved a fight to separate the election of judges from the election of school superintendents and to remove education from the partisan political process. The official organization did not become involved in political races but was active in the government, nonetheless. This early period represented a growing awareness of the organization’s solidarity with other state’s education organizations as well as the National Education Association. Idaho members attended the NEA’s conference for the first time in 1898 and continued to be involved in the larger organization. The relationship with the National Education Association would become much tighter and more significant as Idaho came to rely more heavily on its national educational partners. By the mid-1920s, the ISTA had evolved from its roots as a frontier organization of loosely connected teachers and administrators numbering only 40 or 50 to a powerful association of state-wide educators dedicated to the welfare of children and teachers throughout Idaho with membership numbers approaching 3,000. The Association achieved an immense amount in these early years. It implemented an educational system that was cohesive across the state, ensuring that all children could expect to receive a relatively similar education regardless of their residential location. It implemented an early set of teacher training standards, so children could be assured of a consistently qualified teacher at the chalk board. And the Association began the effort to ensure teachers could be secure in their employment with the state. Little did members know what challenges would face them in the next 15 years.

- 20. 19 1900, Cole School Boise

- 21. 20 Schools Then and Now: Lowell Elementary, Boise The teacher’s role has remained consistent for many generations, but classroom needs have changed dramatically over the years. Today, Idaho boasts many modern, state-of-the-art school buildings. Some of the most up-to-date buildings are beautiful historic schools that have undergone renovations. Reusing these solid community structures reminds citizens where we started and how far we’ve come by honoring the buildings from which neighborhoods and communities have sprung. In the late 19th century, Idaho teachers occupied log cabins, tents, or other simple and rustic structures where students gathered for instruction. Teachers in remote locations had to serve not only as academic instructors, but as wood gatherers, janitors, and disciplinarians. In the late 1920s, the Idaho Journal of Education published an article stating that “the old boxcar type of [school] building, poorly situated, poorly lighted, and poorly ventilated is no longer tolerated.” The IEA provided floor plans for a modern school, complete with indoor plumbing and cloak rooms. According to the article, “An adequate school plant — sanitary, spacious, cheerful — built around the needs of the child and the school, preserves the health of school children and helps to improve individual and community life and to insure a better race.” In the 1920s and 1930s, however, school districts abandoned many small, rural school houses when consolidation called for the construction of larger facilities for multi-community student bodies. In some urban settings, many communities continually remodeled and updated their neighborhood schools. Lowell Elementary in north Boise is one of those schools and represents changes to schools across the state. It has changed significantly over its nearly 100-year history. Originally designed on the “unit plan” that allowed for future expansion, Lowell was built in three stages. The first floor and basement were completed in 1913, 1902, Lost River School 1926, Lowell Elementary School

- 22. 21 followed by the second floor in 1917. The school initially housed only grades 1-4, and back then, lunch period lasted 90 minutes to allow students time to go home to eat. By the mid-1920s, Lowell expanded up to 8th grade, and a 1926 addition on the north gave the school four more classrooms, a second-floor office, and a basement auditorium. The Parent-Teacher Association started a hot lunch program in 1944, with ten tables built by volunteer fathers. With the enrollment increase following World War II, the school added playground equipment in 1946 and eight new classrooms on the south side in 1947, as well as a library. The 1947 addition reflects the Art Deco style of the period. During the energy crisis of the 1970s, another remodel lowered Lowell’s ceilings, added fluorescent lighting, and installed smaller windows, all in an effort to conserve energy. In March 2006, voters approved a bond levy providing for additional upgrades and renovations to several Boise school buildings, including Lowell. In 2010, new heating and cooling systems and more energy and water conservation upgrades were done. That same year, Lowell added a computer lab with internet-ready SMART Boards and projectors. Over the years, the IEA has recognized Lowell for its outstanding volunteer efforts from families and staff, and the U.S. Department of Education chose Lowell Elementary in 1994 as a Blue Ribbon School. In the 2000-2001 school year, Lowell began its English Language Learners program, celebrating a new chapter in student body diversity. Still offering grades K-6, Lowell Elementary’s motto is “Educating all students since 1913… For today and beyond.” Lowell stands as an example of the dozens of Idaho school buildings that have not only endured for more than a century but have adapted to the ever- changing needs of Idaho students. o 2011, Lowell Elementary School 1939, Lowell Elementary School

- 23. 22 IEA and the NEA 1898 Idaho teachers attend the National Education Association’s convention in Washington, D.C., for the first time. 1920 The Idaho State Teachers Association (which changed its name to the Idaho Education Association in 1927) affiliates with the NEA. 1947-48 IEA incorporates and unifies with the NEA. 1968 NEA provides financial and staff assistance to the IEA’s efforts to impose sanctions on Idaho, declaring it unethical for out-of-state teachers to take jobs in Idaho. 1970 IEA’s executive committee approves participation in the new NEA UniServ program for hiring staff to work at the local level. Boise teacher Jack White is employed as the first UniServ director in the country. IEA dubs these staff members “region directors.” 1970s Northwest Nazarene College student Mike Poe is elected Student NEA vice president. 1970s Louise Jones, New Meadows, helps found the NEA Women’s Caucus and the NEA Women’s Leadership Training program. Since 1980 Five IEA members receive NEA Human & Civil Rights Awards: Frances Paisano, Lapwai — Leo Reano Award; Sonia Hunt, Nampa — George I. Sanchez Award; Pete Espinoza, Minidoka County — George I. Sanchez Award; Grace Owens — Martin Luther King, Jr. Award; Sam Cikaitoga (posthumously), Fremont County — Ellison Onizuka Award. Also, an IEA-nominated human rights advocate, Tony Stewart from Coeur d’Alene, receives the H. Council Trenholm Memorial Award. 1986 With NEA’s assistance, the IEA hires a full-time organizer for education support professionals. 1986 Sue Hovey, Moscow, is elected to one of the nine positions on the NEA Executive Committee. She is re-elected in 1989 and serves the maximum two terms of three years each. 1997 Dan Sakota, Rexburg, is elected to one of nine positions on the NEA Executive Committee. He is re-elected in 2000 and serves the maximum two terms of three years each. 1997 IEA implements the NEA’s KEYS (Keys to Excellence in Your Schools) program in several Idaho schools. The program continues and expands over the next few years. 2003 NEA bestows its national Educational Support Professional of the Year Award on Marty Meyer, a Coeur d’Alene custodian and Association activist. 2008 Educator-astronaut Barbara Morgan, IEA member and former McCall- Donnelly teacher, receives NEA’s Friend of Education Award, the Association’s highest honor.

- 24. 23 NEA Public Schools: Fulfilling the American Dream: President Clinton at the National Education Association Regional Assembly 1990s Memorabilia

- 25. 24 B attling for legitimacy and credibility as an organization and a profession had occupied much of the ISTA’s effort in the first decades of the 20th century. By 1926, a great deal of work toward that end had been accomplished. The Association hired and named its first Executive Secretary that year, John I. Hillman, and, in 1927, altered its constitution and re-branded itself the Idaho Education Association. The constitutional changes provided for seven district associations and the creation of local associations, with each local invited to send representatives to the annual Delegate Assembly in proportion to its membership in the IEA. The goal was to bring the Association to the teachers, who felt as 1926-1940 Chapter 2 o The 1920s were an exciting time for the Idaho State Teachers’ Association. g The organization hired John I. Hillman as the first staff member and changed the name to reflect its broad mission for education throughout Idaho. g But just as the Association found its legs, the Depression hit with such economic force that the organization needed a new focus: making sure that the state provided adequate funding for education. g The Depression had an immense impact on education in Idaho. g There was a massive decline in educational funding, caused by numerous events of the decade, not least of which were the extremely high rate of foreclosures and the corresponding decline in property tax revenue. g The funding shortages caused schools to close, leaving rural children, especially, with no place to attend school. g The newly named Idaho Education Association took the state to task, working hard to secure a funding source and hold the state accountable for its constitutional mandate to establish and maintain free public schools. g The IEA also worked very hard during this difficult time to make both the rural and urban educational systems attractive to the most qualified teachers. g This meant raising teacher certification standards and making education in Idaho more efficient. g By the time the United States entered World War II, the IEA had achieved a number of critical successes for education in Idaho in spite of the difficult period that was now behind it. Fighting for Idaho’s Children During Tough Times

- 26. 25 though policy too often was created by administrators who did not understand the challenges of daily life in the classroom. The changes caused IEA membership to jump from about 60% to as high as 97% of all Idaho teachers, provoking a later columnist in the Association’s newsletter to look back on this period and declare that “the teachers took over.” In concert with the organization’s 1927 name and organizational changes, the journal published by the ISTA as The Idaho Teacher since 1919 was re-named the Idaho Journal of Education. Finally, 1927 saw the Idaho Legislature adopt the ISTA’s recommended legislation requiring at least two years of normal school education for elementary school teachers. Thus, by the late 1920s the Idaho Education Association (IEA) had succeeded in establishing itself as the leader in all educational issues with membership in the 3,000-4,000 range. Having succeeded on many fronts, the IEA nevertheless recognized that as long as people’s vision for education evolved and changed, the Association would always work on behalf of Idaho’s children. The years between 1926 and 1940 represented a critical period for children in Idaho. Faced with serious issues related to educational funding and the worldwide Depression, Idaho educators used the clout they gained during the Association’s formative years to battle for a reliable funding source. Misuse of endowment funds combined with Depression-related declines in county property taxes left educators and lawmakers scrambling for a solution without the uncertainties and monetary discrepancies between counties as revenues from the property tax. Facing lawmakers who had never been asked to appropriate state money for education, the IEA led intense debates advocating an increased role for the state in education funding. The 1930s became a decisive period for establishing a state funding mechanism and for protecting the state endowment fund, as well as convincing state leaders to view public education as a perpetual state obligation, not just acting as a hero during tough economic times. It was also a significant era for gains in equalization of education across and within counties, as well as improved administrative efficiencies. Not only did the Depression bring on a funding crisis, it also created a nationwide surplus of teachers. In response to this growing problem, the IEA continued to push the State of Idaho to improve its teacher standards in the 1930s so as to discourage poorly-trained, out-of-work teachers from flooding the state and bringing the level of Idaho’s education down. As part of its continued effort toward the professionalization of education, the IEA aimed to give the State Board of Education full 1927, IEA newsletter cartoon on state education support

- 27. 26 power over certification standards and urged the legislature to implement a salary schedule that would attract the best and most highly qualified teachers. Finally, the IEA continued to wrestle with the best way to provide an education for all students when only 17% pursued a college education and the remainder of students went into agriculture and other vocational trades. The IEA emerged from the rocky 1930s an even stronger organization with a wide base of support, improved status and expectations for education, and friends in the statehouse who supported its mission. The Depression and the Impact on Educational Funding The Depression had severe consequences for Idaho children seeking education. The IEA’s biggest struggle in the 1930s was protecting the supposedly untouchable endowment fund and creating a reliable source of funding in the face of declining property tax revenues. The majority of educational funding had always come from county property taxes, creating disparate educational opportunities from county to county, a situation magnified by the extremely high number of farm (and other property) failures from the late 1920s through the 1930s. Funding had been an issue since Idaho became a state in 1890. The federal government provided a land grant to Idaho, consisting of sections 16 and 36 in every township in the state. The total acreage amounted to approximately 3,000,000 acres, proceeds from which were to be used to fund public schooling. Some land exchanges were approved for remote and forested lands that were deemed useless for fundraising, and all money raised from the final inventory of land was to be placed into the state’s endowment fund, a permanent school fund. The Idaho Constitution permitted the fund to be used for loans on farm mortgages and certain types of bonds. Then, the accrued interest was applied annually to the benefit of the common schools. That interest was never enough to support annual school budgets, so the remaining demands were met through county and local district taxes. At one time, state law required county commissioners to pass a levy sufficient to raise $15 per pupil of school age, but any amount above that — up to a maximum set by law — was left up to the voters. Additional monies approved by voters above the minimum set by law could be used for necessities, such as a school wagon to transport children to school or other capital equipment. Unfortunately, the special tax limitations placed on districts prevented any desire or momentum by local school boards to raise salaries or provide more and improved equipment for classrooms. Thus, in 1920, State Superintendent Ethel E. Redfield requested the ISTA’s support for legislation that would remove caps on the maximum special levy. 1928, Teacher and students with homemade globe

- 28. 27 Idaho’s Endowment Fund Things got decidedly more complicated when the endowment fund came under attack. The story began in the fall of 1928, when Idaho voters were asked to vote for a constitutional amendment (H.R. 10) which would expand the allowed uses for endowment funds. In addition to the ability to loan the money on first mortgages for improved farms within the state, as well as on state, United States, or school district bonds — all of which were provided for in the existing state constitution — the measure would increase permitted uses to include county, city, and village bonds. The IEA was gravely concerned that such expenditures would deplete endowment funds and lead to an increase in taxes to make up the difference. “Certainly we should vote against it,” the Journal urged, but the IEA also encouraged “every school man [to] see that his community has a clear understanding of the problem involved.” Despite these pleas, voters approved the amendment. Soon thereafter, in 1928, a routine annual audit of Boise City’s Independent School District raised eyebrows about potentially missing income from state endowment funds, causing the district to investigate and question state leaders as to where the money might have gone. A few key documents divulged that concerns over state management of the endowment fund began ten years earlier during Moses Alexander’s term as Idaho’s governor between 1915 and 1919. During Alexander’s term, an official report was provided to the governor and the legislature disclosing a $400,000 shortage in the endowment fund. Since no action was taken on the concerns raised at that time, the State Board of Education penned a letter to the succeeding Governor, C.C. Moore, insisting on answers to questions about the fund. Still, there was no resolution and no record of the Board’s letter ever reaching the legislature. Upon discovering the documents that indicated the existence of a longstanding problem, the Boise School Board contacted all of the Class A Independent School Districts in the state and asked them to join in a preliminary audit of the endowment funds, with a view toward a full audit (at a cost of $75,000) of the fund back to statehood. The IEA, outraged over the casual nature of the state officials’ past responses to the problem, argued that it was “unlawful for even one cent ever to be taken from these funds for any purpose… If there has been any transfer, therefore, it has been done unlawfully, and the money has been expended unlawfully.” Whether the state actually had lost money or it had been transferred to a different fund was irrelevant to educators; money had been taken The IEA argued that it was “unlawful for even one cent ever to be taken from these funds for any purpose… If there has been any transfer, therefore, it has been done unlawfully, and the money has been expended unlawfully.” 1930, Principal and students at reading table

- 29. 28 from the educational budget, and “the payers of school taxes have had their burden increased accordingly. If a known loss of $400,000 with a probable additional loss of from $100,000 to twice or three times that amount… does not warrant a $75,000 audit, then there has never been warrant for the audit of any account!” Over the next ten years, the IEA aimed to unveil exactly how the endowment funds had been mismanaged and fought for renewed responsible management of the money. The Idaho Constitution’s provision for loans and bonds to be granted from the fund had laid the groundwork for corruption and graft. The IEA discovered that hundreds of thousands of dollars from the endowment fund had been raided for many unauthorized uses, including untraced transfers to the state’s general fund and loans to state officials’ relatives. Additionally, the state had sold thousands of endowment acres to corporations despite the law’s limit of such sales to 320 acres. The potential for corruption had only increased with the passage of H.R. 10 in 1928. The IEA was saddened and disgusted with the apparent misdeeds by state officials charged with guarding the funds in trust, and it pledged to find solutions. It was widely feared that without legal protection and changes to the law, this key funding source for education in Idaho was in serious jeopardy. By bringing the issue to the public and rattling cages until the issues were resolved, the IEA and the Idaho School Trustees’ Association tried to ensure a protected endowment fund for Idaho’s children. In editorial after editorial in the late 1920s, the IEA took the legislature to task for an inadequate appropriation for the audit and demanded that the constitution be amended to repeal recent allowances for expenditures on city and village bonds. The Association also called for a repeal of the Farm Mortgage Fund and recommended that a study be made on “the farm loan problem.” If the farm loans were to continue with these funds, the Association argued, there had to be drastic reforms in loan procedures, for while the state constitution allowed such loans, they had historically resulted in losses to the fund. Furthermore, the IEA came out against the law that allowed for the sale (at less than $10 per acre) of lands obtained by foreclosure. Shocked by the blatant dishonesty of state officials, the IEA deployed a great deal of rhetoric in the fight. They referenced Diogenes and his search for an honest man with a lantern in broad daylight and pointed to the folly of providing character education in the schools while “the attitude of the people toward this heritage is in doubt.” Still, the pleas fell on deaf ears. 1930, Students in line for health inspections 1930, Teachers working in the community

- 30. 29 When the stock market crashed in 1929 and the country plummeted into a headlong financial depression that lasted for a decade, the implications of Idaho’s farm loan provision were more readily apparent. By the early 1930s, the IEA estimated that permanent education funds were losing between $90,000 and $100,000 annually from farm loans, and that as much as 40% of the monetary value of the farm loans was nonproducing because of foreclosure or a failure to pay either interest or principal. The mismanagement of education funds was a subject in the 1932 gubernatorial campaign, when both Republican and Democratic candidates offered opinions about the debacle in their paid political advertisements. That year, the Democrat, Ben Ross, won. In the meantime, long-term changes were in the works. Trustees from the Boise School District had filed a lawsuit against the state of Idaho to force a return of endowment fund money taken for the Farm Mortgage Fund. While the lawsuit was making its way through the courts, the IEA’s new Endowment Committee came up with a variety of recommendations for reform. The first was an effort to better control who served on the State Board of Land Commissioners. The IEA hoped for a more permanent body and personnel and, toward that end, suggested that the Idaho Supreme Court appoint members for lengthy terms and include a justice from the Supreme Court as well as a member from the State Board of Education. The Association urged the legislature to grant the Land Board complete control of the endowment funds and to require that body to provide an annual report of endowment transactions to the legislature. Furthermore, the organization advocated discontinuing investments that had resulted in losses and called for a repeal of laws that diverted principal or income of endowment funds for non-educational use. Despite the disclosure of the abuse of the permanent school fund, the laws did not change until the end of the 1930s. The Idaho Supreme Court did rule in 1934 that amendments to the constitution providing for endowment funds to be invested in state warrants and school district bonds were unconstitutional, but by 1937, the Idaho Legislature had done very little to stop the misuse and “rape” of endowment money in the law. To the pleasure of the IEA, individuals serving on the Land Board made great strides toward discontinuing the old policy 1930, Napping children in school 1930, Feeding children during the Depression, snacking at school “Equality of educational opportunity is the birthright of every American child.” — IEA Journal, 1927

- 31. 30 of investing money in patently unsafe ways, but the laws prohibiting such investments had not changed dramatically. Therefore, the IEA maintained its long list of objectives to accomplish at the statehouse, but ultimately it was left to depend on the goodwill of those serving on the State Land Board for most of the 1930s. As the decade progressed, other financial issues floated to the top of the IEA’s heap of battles, and the organization began to flank the funding issue from another angle. State Funding for Education and Equalization Even before the Depression hit, the IEA recognized and struggled with the fact that the State of Idaho did not provide a single bit of funding to educate Idaho’s children, despite the state’s constitutional mandate for the legislature to “establish and maintain a general, uniform, and thorough system of public, free common schools.” As self-appointed visionary and watchdog for the state’s schoolchildren, the Association faced the issue head-on and argued that the state was shirking its responsibility to educate its citizens. By leaving the majority of funding up to the counties and offering no state contribution, the state had allowed vast inconsistencies in educational opportunities between counties. The disparity between rich and poor children and their differing access to a quality education grew over time. In 1927, the IEA proclaimed in its Journal that “Equality of educational opportunity is the birthright of every American child.” Idaho’s sole reliance on the endowment fund and property taxes, in conjunction with its poor method of federal fund distribution and the state law’s discrepancy between the levy allowed for common versus independent school districts, made the counties unable to provide equal education either within their counties or across the many counties in the state. All districts utilized the mill formula for levies, in which a mill represented 1/1000 of a currency unit — in this case, the United States dollar. Common school districts, typically found in rural areas where students of many ages were taught by a single teacher, were permitted to levy only up to 10 mills on property values, but independent districts, usually found in wealthier urban areas, were allowed a 30-mill levy. Yet the Association’s research team found that many courts had ruled in favor of educational uniformity in public schools. Therefore, the IEA concluded that state intervention was needed, because “the rich sections tax themselves… lightly to provide very good schools, while the poor ones tax themselves very heavily and still do not provide satisfactory educational opportunities.” The IEA ran myriad articles over the next few years showing calculations and disparities of tax amounts, and pleading with voters that “the school tax situation demands careful study and analysis and scientific adjustment, which only selfish The IEA’s first success on behalf of state funding came in 1933, when the Idaho Legislature passed House Bill 157, Idaho’s first official education equalization act. a. 1932, Coeur d’Alene primary student with crepe paper dress she designed and made as one of the projects in Ms. Bayne’s class b. 1933, Hailey harmonica band from Hailey Central School, music education c. 1934, Play day at Albion Normal School d. 1930, Primary school projects in Coeur d’Alene. Practical art and number work were achieved by this method e. 1939, Home economics for boys f. 1939, One horse power school bus, rural district

- 33. 32 and unpatriotic interests can oppose.” The Association found that other states provided appropriate annual funds for public schools, while Idaho provided no revenue source for the elementary schools, and merely matched federal funds for vocational work in high schools to the tune of less than one percent (1%). Idaho was, according to the IEA, dodging its duty to educate its citizens. The Depression highlighted the funding problem more than ever. Discrepancies grew in the face of failing properties and increasing foreclosures, resulting in lower funding from property taxes. Rural schools were forced to close because there was no money for teachers or maintenance of properties. As the problem compounded, the IEA advocated two related policy changes. First, the organization pushed for a state funding mechanism that was not tied to property taxes. Second, the IEA urged that any appropriated state money be used for equalizing education across the counties. Using its newsletter, the Idaho Journal of Education, the IEA forcefully put forth its ideas. First it pointed out that while it appeared that mines, lumber, and public utilities bore the biggest burden of school funding, in fact it was “the average property owner pay[ing] the far greater part of the taxes — the farmer, the stockraiser, the average businessman, the home owner in the city.” It was time, said the IEA, for the state to take the burden off the property owner. In 1930, the organization’s new Equalization Tax Committee noted that “cheapness does not make for excellency” and recommended raising new sources of state revenue. Ideas that were floated included a graduated income and inheritance tax, or luxury and natural resource taxes. Association President John W. Condie suggested diverting a share of the discovery and development of the state’s natural resources to education. The IEA’s first success on behalf of state funding came in 1933, when the Idaho Legislature passed House Bill 157, Idaho’s first official education equalization act. Having experienced the closure of multiple rural schools due to a lack of funds in 1932-1933, the state finally was motivated to help. The new law required each district to levy an additional minimum of 3 mills and pledged state money to make up the difference until each classroom unit had a budget of $800. In years when state funds were unavailable, the Education Board was given authority to apportion the percentage of available money. The IEA was happy with the legislation for two reasons. First, the Idaho law guaranteed a minimum financial program, while similar laws in other states were conditional. Second, the county levy was flexible, making it possible to reduce county property tax by substituting state revenue when available. However, the IEA did see flaws in the legislation. An editorial argued that the law would not benefit wealthy counties or classroom units, but that the law provided “a very fine foundation” for the distribution of state funds. In practice, the law worked well from the start. Before the law’s passage, at least 30 schools had closed due to lack of funds. But during the two years after the law’s passage, none were forced to shut down. For some of the poorest schools, the law had cut the property tax levy in half and was credited with saving education in these counties. “Organization of education for efficiency, with equalization of opportunity is the underlying principle — a square deal for every underprivileged child.” — IEA President John W. Condie, 1931

- 34. 33 However, the IEA viewed the state’s meager initial appropriation and a lack of secure and permanent funding as a challenge to lobby for a reliable funding source. An incredible 91.6% of the state’s school revenue was still generated by property taxes, and it was predicted that if the state would approve $2.5 million in permanent funding, county levies could be reduced even further. The fact remained that “the wealth per classroom unit… of the richest county is 320 per cent of that of the poorest.” Therefore, the IEA advocated raising the $2.5 million by passing some of the tax options mentioned above and by moving toward greater equalization and a more even distribution of funds. As the struggle to obtain permanent funds went forward, the IEA researched and led debates over the best way to raise the money. The Association discussed annual appropriations from the General Fund (seen as subject to the whims of the legislature and therefore unreliable), earmarked dollars, and money from specific taxes. As a result, the state experimented with many taxes during the 1930s, including the first sales tax passed in 1935 at a rate of 2% on retail purchases (repealed by voters shortly thereafter), a tax on mines, and another one on alcohol. The alcohol tax that passed in the 1930s began an income stream for schools that has lasted for close to 80 years. But the voters’ repeal of the sales tax led the IEA to conclude that the state had not lived up to the promise of the equalization mandate. The organization settled upon reviving the sales tax law as the best method to provide income for equalization among the schools and lobbied hard for it as the chosen method to complete the equalization program. Rural Schools: Consolidation and Teacher Training Funding was not the only issue affecting the efficacy of rural schools. The Depression era also unveiled the degree to which rural school children were underprivileged when it came to qualified and experienced teachers as well as a consistent educational program. At the end of the 1920s, statistics on Idaho public schools showed just how serious the rural school problem was, with Idaho possessing 70 four-room schools, 62 three-room schools, 198 two-room schools, and a truly overwhelming 820 one-room schools. Data also showed that at the state level, Idaho provided little supervision over these rural schools, so there was great inconsistency between these schools and their teachers compared with those in more urban settings. For instance, the Idaho State Board of Education found that 90% of teachers in rural schools met only minimum certification requirements of nine weeks of training. Those 1939, Teacher and students reading