Seizure Disorder Basics Guide

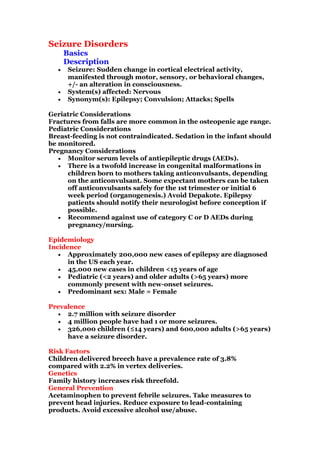

- 1. Seizure Disorders Basics Description • Seizure: Sudden change in cortical electrical activity, manifested through motor, sensory, or behavioral changes, +/- an alteration in consciousness. • System(s) affected: Nervous • Synonym(s): Epilepsy; Convulsion; Attacks; Spells Geriatric Considerations Fractures from falls are more common in the osteopenic age range. Pediatric Considerations Breast-feeding is not contraindicated. Sedation in the infant should be monitored. Pregnancy Considerations • Monitor serum levels of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). • There is a twofold increase in congenital malformations in children born to mothers taking anticonvulsants, depending on the anticonvulsant. Some expectant mothers can be taken off anticonvulsants safely for the 1st trimester or initial 6 week period (organogenesis.) Avoid Depakote. Epilepsy patients should notify their neurologist before conception if possible. • Recommend against use of category C or D AEDs during pregnancy/nursing. Epidemiology Incidence • Approximately 200,000 new cases of epilepsy are diagnosed in the US each year. • 45,000 new cases in children <15 years of age • Pediatric (<2 years) and older adults (>65 years) more commonly present with new-onset seizures. • Predominant sex: Male = Female Prevalence • 2.7 million with seizure disorder • 4 million people have had 1 or more seizures. • 326,000 children (≤14 years) and 600,000 adults (>65 years) have a seizure disorder. Risk Factors Children delivered breech have a prevalence rate of 3.8% compared with 2.2% in vertex deliveries. Genetics Family history increases risk threefold. General Prevention Acetaminophen to prevent febrile seizures. Take measures to prevent head injuries. Reduce exposure to lead-containing products. Avoid excessive alcohol use/abuse.

- 2. Pathophysiology Synchronous and excessive firing of neurons resulting in impairment of normal control of CNS Etiology • Brain tumor • Cerebral hypoxia • Cerebrovascular accident • Convulsive or toxic agents (e.g., lead, alcohol, picrotoxin, strychnine) • Drug or alcohol overdose/withdrawal • Eclampsia • Exogenous factors, triggers (e.g., sound, light, cutaneous stimulation) • Fever, acute infection, or metabolic disturbance • Head injury • Heat stroke Commonly Associated Conditions Infections, tumors, drug abuse, alcohol and drug withdrawal, trauma, metabolic disorders Diagnosis • Differentiate first between epileptiform seizures and nonepileptiform seizures (NESs). • If NES are psychogenic; often are associated with history of sexual abuse o Psychogenic NES is usually associated with a history of psychiatric conditions. Physiologic seizures are true cortical events and often require acute intervention. Hyperthyroidism Hypoglycemia Nonketotic hyperglycemia Hyponatremia Uremia Porphyria Hypoxia Confusional migraine Transient ischemic attack Narcolepsy/sleep disorder Toxin • International classification of seizures: o Generalized seizures: o Absence o Atonic o Juvenile myoclonic Myoclonic: Repetitive muscle contractions Tonic–clonic: Tonic phase: Sudden loss of consciousness; clonic phase: sustained contraction followed by rhythmic contractions of all 4 extremities; postictal phase: headache,

- 3. confusion, fatigue; clinically, hypertensive, tachycardic, and otherwise hypersympathetic o Febrile seizures: Age between 3 months and 5 years Fever without evidence of any other defined cause for seizures Recurrent febrile seizures probably do not increase the risk of epilepsy o Symptomatic focal epilepsies o Complex partial seizures o Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: Most commonly seen in ICU patients-no tonic clonic activity seen so must diagnose with bedside EEG o Status epilepticus: Repetitive generalized seizures without recovery between seizures; considered a neurologic emergency. History • Eyewitness descriptions of event • Patient impressions of what occurred before, during, and after the event • Screen for etiologies. • Provoking or ameliorating factors for the event including sleep deprivation • Ask about bowel or bladder incontinence, tongue biting, other injury, automatisms. Physical Exam Thorough neurologic exam Diagnostic Tests & Interpretation A negative EEG does not rule out a seizure disorder. • Sleep deprivation is helpful prior to EEG to identify positive spike wave formations. • Video EEG monitoring is used to differentiate psychomotor NES from true cortical events Lab Initial lab tests • Serum tests: Glucose, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, BUN, ammonia • AED levels • Drug and toxic screens: Include alcohol. • Complete blood count (CBC): Rule out infection. Follow-Up & Special Considerations • Consider an arterial blood gas determination. • Drugs that may alter lab results: AED therapy may affect the EEG results dramatically.

- 4. • Inadequate AED levels: May be altered by many medications, such as erythromycin, sulfonamides, warfarin, cimetidine, and alcohol. • Disorders that may alter lab results: Pregnancy decreases serum concentration. • Consider HLA testing in Asian patients. Imaging Imaging is recommended for new onset seizures when localization- related epilepsy is known or suspected, when the epilepsy classification is in doubt, or when an epilepsy syndrome with remote symptomatic cause is suspected. MRI is preferred to CT because of its superior resolution, versatility, and lack of radiation Initial approach • Brain MRI: Superior in evaluation of the temporal lobes • CT scan of brain: Indicated routinely as initial evaluation esp in ER • Bone scan to determine bone mineral density (BMD) – generally done if pt on older AEDs such as Dilantin and Tegretol Diagnostic Procedures/Surgery LP for spinal fluid analysis may be necessary especially if fever or impairment of consciousness Pathological Findings MRI may identify a nidus for seizure activity. Differential Diagnosis • General: o Idiopathic o Acute infection o Trauma o Drug and alcohol withdrawal o Tumor o Conversion disorder: Pseudoseizure o NES o Vascular disease • Additionally: o Infancy (0–2 years): Perinatal hypoxia Metabolic: Hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, vitamin B6 deficiency, phenylketonuria o Childhood (2–10 years): Febrile seizure o Adolescent (10–18 years): Arteriovenous malformations o Late adulthood (>60 years):

- 5. Degenerative disease including dementia Metabolic: Hypoglycemia, uremia, hepatic failure, electrolyte abnormality Treatment • 50-60% presenting with an initial unprovoked seizure will not have a recurrence; 40–50% will have a recurrence within two years (2)[A]. • Starting antiepileptic medications reduces recurrences of seizures, but does not alter long term outcomes (3)[A]. • Evidence is conflicting whether or not to routinely start AEDs in patients with an initial seizure and no focal abnormalities on exam or imaging, though many recommend deferring treatment until a second seizure has occurred (4)[A]. Medication • AEDs of choice: Select from seizure groups below, with attention toward potential side effects. • Choice of AED is based on type of seizure • Monotherapy is preferred whenever possible. Systemic reviews found insufficient evidence on which to base a 1st- or 2nd-line choice among these drugs in terms of seizure control. • Treatment options include: o Carbamazepine (Tegretol) 100–200 mg/d in 1–2 doses; therapeutic range: 4–12 mg/L o Phenytoin (Dilantin) 200–400 mg/d in 1–3 doses; therapeutic range 10–20 mg/L o Valproic acid (Depakene) 750–3,000 mg/d in 1–3 doses to begin at 15 mg/kg/d; therapeutic range 50–150 mg/L o Lamotrigine (Lamictal) 25–50 mg/d; adjust in 100-mg increments every 1–2 weeks to 300–500 mg/d in 2 divided doses. o Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) 300 mg b.i.d., increase to 300 mg/3 days; maintenance 1,200 mg/d o Topiramate (Topamax) 50 mg/d; adjust weekly to effect; 400 mg/d in 2 doses, maximum 1,600 mg/d o Pregabalin (Lyrica) o Lacosamide (Vimpat), particularly if refractory seizures • Alternative drugs (in addition to any of the preceding): o Phenobarbital: 50–100 mg b.i.d.–t.i.d.; therapeutic range 15–40 mg/L o There is evidence to suggest long-term use of phenobarbital may impair cognitive ability. o Primidone (Mysoline) 100–125 mg qhs; adjust to maximum of 2,000 mg/d in 2 doses. • Contraindications: Refer to manufacturer's profile of each drug.

- 6. • Precautions: Doses should be based on individual's response guided by drug levels. • Consider cautioning about increased risk of suicide, but risk of untreated seizures is far greater than increased risk of suicide (5)[A]. • Patients are susceptible to SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy) possibly due to cardiac arrhythmia Additional Treatment Issues for Referral • Patients should be referred to and followed by a specialist regularly. • Frequency of visits is based on severity and patient's wishes; maximum of 1 year between visits. Complementary and Alternative Medicine • There is no evidence that any complementary medicines improve seizures, but they may induce serious drug interactions with prescribed AEDs. • Psychological therapies may be used in conjunction with AED therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation, biofeedback, and yoga all may be helpful as adjunctive therapy (6)[C]. • Patients with NES should be referred for psychotherapy. Surgery/Other Procedures • Resection for seizures that fail traditional therapy • Vagus nerve stimulation In-Patient Considerations Initial Stabilization • Protect the airway, and if possible, protect the patient from physical harm; do not restrain. • Administer acute AEDs. Admission Criteria Outpatient therapy is usually sufficient except for status epilepticus. Ongoing Care Follow-Up Recommendations • Maintain adequate drug therapy; ensure compliance and/or access to medication. • Drug therapy withdrawal may be considered after a seizure- free 2-year period. Expect a 33% relapse rate in the following 3 years. Patient Monitoring • Monitoring of drug levels and seizure frequency • CBC and lab values (e.g., calcium, vitamin D) as indicated, BMD

- 7. • Monitor for side effects and adverse reactions. • All patients currently taking any AED should be monitored closely for notable changes in behavior that could indicate the emergence or worsening of suicidal thoughts or behavior or depression. Diet Ketogenic diet may be beneficial in children in conjunction with AED therapy. Patient Education • Stress the importance of medication compliance and the avoidance of alcohol and recreational drugs. • Individuals with uncontrolled seizures should be encouraged to avoid heights and swimming. • State driving laws: epilepsyfoundation.org – most states require a minimum of 6 months seizure free • http://epilepsy.org Prognosis • Depends on type of seizure disorder • ∼70% will become seizure-free with initial appropriate treatment, but 30% will continue to have seizures. The number of seizures within 6 months after first presentation is the most important factor for remission. • Approximately 90% who are seen for a first unprovoked seizure attain a 1–2 year remission within 4 or 5 years of the initial event (2)[A]. • Life expectancy is shortened in persons with epilepsy. • The case-fatality rate for status epilepticus may be as high as 20%. Complications Drug toxicity. References 1. Gaillard WD, Chiron C, Cross JH, et al. Guidelines for imaging infants and children with recent-onset epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2147–53. 2. Berg AT, et al. Risk of recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure. Epilepsia. 2008;49(1):13–8. 3. Arts WF, Geerts AT, et al. When to start drug treatment for childhood epilepsy: the clinical-epidemiological evidence. Eur J Paediatr. Neurol. 2009;13:93–101.

- 8. 4. Haut SR, Shinnar S, et al. Considerations in the treatment of a first unprovoked seizure. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:289–96. 5. Hesdorffer DC, Kanner AM. The FDA alert on suicidality and antiepileptic drugs: Fire or false alarm? Epilepsia. 2009;50:978– 86. 6. Marson A, Ramaratnam S. Epilepsy. Clin Evid Concise. 2005;13:362–4. 7. Levy R, Cooper P. Ketogenic diet for epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;3: CD001903. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001903. Seizures, Febrile; Status Epilepticus Codes ICD9 • 345.90 Epilepsy, unspecified, without mention of intractable epilepsy • 779.0 Convulsions in newborn • 780.39 Other convulsions Snomed • 128613002 seizure disorder (disorder) • 84757009 epilepsy (disorder) • 87476004 convulsions in the newborn (disorder) Clinical Pearls • Encourage helmet usage to minimize head injuries. • In order for the patient to be allowed to drive, he or she must be seizure-free from a minimum of 3 months up to a year depending on state requirements. • Drug initiation after a single seizure will decrease risk of early seizure recurrence (8)[A] but does not affect long-term prognosis of developing epilepsy (9)[A].