Conjuring%20 Clouds%20 Tr%2011

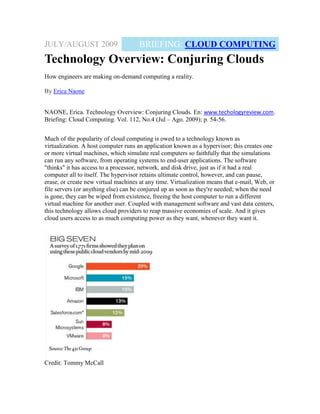

- 1. JULY/AUGUST 2009 BRIEFING: CLOUD COMPUTING Technology Overview: Conjuring Clouds How engineers are making on-demand computing a reality. By Erica Naone NAONE, Erica. Technology Overview: Conjuring Clouds. En: www.techologyreview.com. Briefing: Cloud Computing. Vol. 112, No.4 (Jul – Ago. 2009); p. 54-56. Much of the popularity of cloud computing is owed to a technology known as virtualization. A host computer runs an application known as a hypervisor; this creates one or more virtual machines, which simulate real computers so faithfully that the simulations can run any software, from operating systems to end-user applications. The software "thinks" it has access to a processor, network, and disk drive, just as if it had a real computer all to itself. The hypervisor retains ultimate control, however, and can pause, erase, or create new virtual machines at any time. Virtualization means that e-mail, Web, or file servers (or anything else) can be conjured up as soon as they're needed; when the need is gone, they can be wiped from existence, freeing the host computer to run a different virtual machine for another user. Coupled with management software and vast data centers, this technology allows cloud providers to reap massive economies of scale. And it gives cloud users access to as much computing power as they want, whenever they want it. Credit: Tommy McCall

- 2. The dream of on-demand computing--a "utility" that can bring processing power into homes as readily as electricity or water--arose as soon as computers became capable of multitasking between different users. But early attempts to create this capacity were too restrictive--for example, limiting users to a particular operating system or set of applications. With virtualization, a user can write applications from scratch, using practically any operating system. And users don't have to write their own applications: cloud providers, and companies that partner with them, can offer and customize a variety of sophisticated services layered on top of the basic virtual machines. This means that developers interested in, say, rolling out a new social-networking website don't need to design and deploy their own supporting database or Web servers. By allowing users and developers to choose exactly how much they want in the way of computing power and supporting services, cloud computing could transform the economics of the IT and software industries, and it could create a whole raft of new online services (see "Virtual Computers, Real Money"). "Cloud computing is a reincarnation of the computing utility of the 1960s but is substantially more flexible and larger scale than the [systems] of the past," says Google executive and Internet pioneer Vint Cerf. The ability of virtualization and management software to shift computing capacity from one place to another, he says, "is one of the things that makes cloud computing so attractive." Virtualization technology dates backs to 1967, but for decades it was available only on mainframe systems. When data centers became common during the Internet boom of the 1990s, they were usually made up not of mainframes but of numerous inexpensive computers, often based on the x86 chips found in PCs worldwide. These computers had hardware idiosyncrasies that made virtualization difficult. While companies like VMware offered software solutions in the late 1990s, it wasn't until 2005 that Intel (soon followed by its rival AMD) offered hardware support for virtualization on x86 systems, allowing virtual machines to run almost as fast as the host operating system.

- 3. The stack: Many clouds rely on virtualization technology that allows computers to simulate many processing and storage servers. Starting with hardware located in data centers, a series of software layers allow these virtual servers to be created and configured on demand. Once a customer no longer needs a virtual server, it can be erased, releasing the underlying hardware resources to serve another computer. By providing computing power in such an elastic way, clouds enable companies to avoid paying for power they don’t need. Credit: Tommy McCall

- 4. Even with the new support, you can't just "plug in a server" and expect to use it for cloud computing, says Reuven Cohen, founder of the cloud-computing platform company Enomaly and the Cloud Computing Interoperability Forum. Instead, cloud computing relies on a series of layers. At the bottom is the physical hardware that actually handles storage and processing--real servers crammed into a data center, mounted in rack upon rack. Although companies are loath to disclose the size of their data centers, John Engates, CTO of Rackspace, says that hosting companies typically build them out in modules of 30,000 to 50,000 square feet at a time. Running on the hardware is the virtualization layer, which allows a single powerful server to host many virtual servers, each of which can operate independently of the others. Customers can change configurations or add more virtual servers in response to events such as increases in Web traffic. (It should be noted that not every cloud provider uses virtual servers; some combine the resources of physical computers by other means.) Then comes the management layer. In place of platoons of system administrators, this layer distributes physical resources where they're needed, and returns them to the pool when they're no longer in use. It keeps a watchful eye on how applications are behaving and what resources they're using, and it keeps data secure. The management layer also allows cloud companies to bill users on a true pay-as-you-go basis, rather than requiring them to lease computing resources in advance for fixed periods of time. Better billing may seem like a small detail, but it has turned out to be a key advantage over earlier attempts to create on-demand computing. Credit: Tommy McCall Cloud providers can offer services on top of the management layer, allowing customers to use cloud-based infrastructure in place of physical hardware such as Web servers or disk arrays. Amazon Web Services' Simple Storage Service (S3), for example,

- 5. allows customers to store and retrieve data through a simple Web interface, paying about 15 cents per gigabyte per month in the United States (with some additional charges for data transfers). The Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2), also from Amazon, provides virtual computers that customers can use for processing tasks. Prices range from 10 cents per hour to $1.25 per hour, depending on the size of the virtual computer and the software installed on it. Beyond infrastructure offerings, however, companies are also providing more sophisticated services, including databases for managing information and virtual machines that can host applications written in high-level languages such as Python and Java, all of which can help developers get a new service or application to market faster. Google's App Engine, for example, gives customers access to the technologies underlying Google's own Web-based applications, including its file system and its data storage technology, Bigtable. Even when these services don't use a layer of virtual servers (App Engine does not), they still allow users to expand and contract their usage with the flexibility that is the hallmark of cloud computing. Perched on top of all these layers are the end-user applications, such as online calendars or programs for editing and sharing photos. By encouraging content sharing and loosening the limits imposed by our computers' local processing abilities, these applications are changing the way we use software. While some--such as Web mail--predate clouds, building such services on clouds can make them more appealing says Rick Treitman, entrepreneur in residence at Adobe Systems and a driving force behind the Acrobat.com suite of applications (which do their computations on a user's computer but draw data from a cloud as needed). For consumers, Treitman says, what's most attractive about cloud applications is their constant availability, regardless of the user's operating system or location, and the ease with which multiple users can share data and work together. But he notes that these qualities can come into conflict: allowing offline access to data stored in cloud applications, for example, offers a convenience to users but can create problems if multiple users access a document, change it offline, and then try to synchronize their efforts. (For more about some of the technical challenges facing cloud computing, see "The Standards Question," p. 59.) While Amazon and other providers make cloud services publicly available, some companies are turning to cloud-computing technologies inside their own private data centers, with the goal of using hardware more efficiently and cutting down on administrative overhead. And once a company sets up its own private cloud, it has a chance to take advantage of additional flexibility. For example, a specialty of Cohen's company, Enomaly, is setting up overflow computing, also known as cloud bursting. A company can host its Web services and applications in its own data centers most of the time, but when a spike in traffic comes along, it can turn to outside providers for supplemental resources instead of turning customers away. Ultimately, clouds could even change the way engineers design the computers that are increasingly embedded in everyday objects such as cars and washing machines. If these low-powered systems can reach out and draw any amount of computing power as needed, then the sky's the limit for what they might do.