Elements for peanut butter

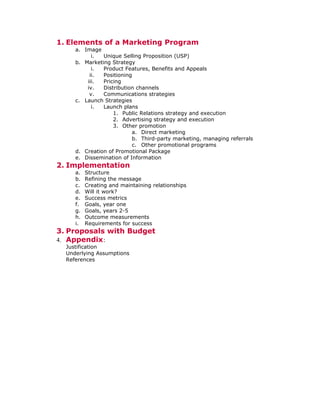

- 1. 1. Elements of a Marketing Program a. Image i. Unique Selling Proposition (USP) b. Marketing Strategy i. Product Features, Benefits and Appeals ii. Positioning iii. Pricing iv. Distribution channels v. Communications strategies c. Launch Strategies i. Launch plans 1. Public Relations strategy and execution 2. Advertising strategy and execution 3. Other promotion a. Direct marketing b. Third-party marketing, managing referrals c. Other promotional programs d. Creation of Promotional Package e. Dissemination of Information 2. Implementation a. Structure b. Refining the message c. Creating and maintaining relationships d. Will it work? e. Success metrics f. Goals, year one g. Goals, years 2-5 h. Outcome measurements i. Requirements for success 3. Proposals with Budget 4. Appendix: Justification Underlying Assumptions References

- 2. PEANUT BUTTER HISTORY There are many claims about the origin of peanut butter. Africans ground peanuts into stews as early as the 15th century. The Chinese have crushed peanuts into creamy sauces for centuries. Civil War soldiers dined on 'peanut porridge.' These uses, however, bore little resemblance to peanut butter as it is known today. In 1890, an unknown St. Louis physician supposedly encouraged the owner of a food products company, George A. Bayle Jr., to process and package ground peanut paste as a nutritious protein substitute for people with poor teeth who couldn't chew meat. The physician apparently had experimented by grinding peanuts in his hand-cranked meat grinder. Bayle mechanized the process and began selling peanut butter out of barrels for about 6¢ per pound. Around the same time, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg in Battle Creek, Michigan, began experimenting with peanut butter as a vegetarian source of protein for his patients. His brother, W.K. Kellogg, was business manager of their sanitarium, the Western Health Reform Institute, but soon opened Sanitas Nut Company which supplied foods like peanut butter to local grocery stores. The Kelloggs' patent for the "Process of Preparing Nut Meal" in 1895 described "a pasty adhesive substance that is for convenience of distinction termed nut butter." However, their peanut butter was not as tasty as peanut butter today because the peanuts were steamed, instead of roasted, prior to grinding. The Kellogg brothers turned their attention to cereals which eventually gained them worldwide recognition. Joseph Lambert, a Kellogg employee who had worked on developing food processing equipment, began selling his own hand-operated peanut butter grinders in 1896. Three years later, his wife Almeeta published the first nut cookbook, "The Complete Guide to Nut Cookery" and two years later the Lambert Food Company was organized. In 1903, Dr. George Washington Carver began his peanut research at Tuskeegee Institute in Alabama. While peanut butter had already been developed by then, Dr. Carver developed more than 300 other uses for peanuts and so improved peanut horticulture that he is considered by many to be the father of the peanut industry. C.H. Sumner was the first to introduce peanut butter to the world at the Universal Exposition of 1904 in St. Louis. He sold $705.11 of the treat at his concession stand and peanut butter was on its way to becoming an American favorite! Krema Products Company in Columbus, Ohio began selling peanut butter in 1908 ~ and is the oldest peanut butter company still in operation today. Krema's founder, Benton Black, used the slogan, "I refuse to sell outside of Ohio." This was practical at the time since peanut butter packed in barrels spoiled quickly and an interstate road system had not yet been built.

- 3. In 1922, Joseph L. Rosefield began selling a number of brands of peanut butter in California. These peanut butters were churned like butter so they were smoother than the gritty peanut butters of the day. He soon received the first patent for a shelf-stable peanut butter which would stay fresh for up to a year because the oil didn't separate from the peanut butter. One of the first companies to adopt this new process was Swift & Company for its E.K. Pond peanut butter ~ renamed Peter Pan in 1928. In 1932, Rosefield had a dispute with Peter Pan and began producing peanut butter under the Skippy label the following year. Rosefield created the first crunchy style peanut butter two years later by adding chopped peanuts into creamy peanut butter at the end of the manufacturing process. In 1955, Procter & Gamble entered the peanut butter business by acquiring W.T. Young Foods in Lexington, Kentucky, makers of Big Top Peanut Butter. They introduced Jif in 1958 and now operate the world's largest peanut butter plant ~ churning out 250,000 jars every day! A Spread of the Peanut Butter Industry At the thought of the word peanut, one would not miss mentioning the legume's most popular use - as peanut butter! Peanut butter is one of the many products that fall under the bread spreads category. (Other well-known spreads include butter, cheese spreads, jams, jellies and marmalades, sandwich spread, and mayonnaise). Like the other spreads, peanut butter is normally added to ordinary bread to give it a distinct and specific flavor. At times, it is used in baking, and also in cooking to create savory sauces for various vegetable, meat, and pasta dishes. Peanut butter is made from roasted, peeled, and ground peanuts mixed with sugar, salt and oil. Peanut butter manufacturers indicated that there is a need to develop the quality of local peanuts. Currently, a substantial percentage of total peanuts used are imported (usually from China) because they are cheaper and have relatively low moisture content. According to a major player, his company uses 50% locally produced peanuts while the remaining 50% is imported. Local peanuts, albeit tastier and with better aroma, cannot be completely relied on because of their high moisture content. Players are critical about the moisture content of peanuts because a high moisture level will cause molds to develop allowing the growth of a carcinogenic substance called aflatoxin. The Department of Health's Bureau of Food and Drugs (BFAD) imposes a limit on the amount of aflatoxin at 20 parts per billion.

- 4. Another concern is the unimproved market base. Sources say the entire spreads industry also suffers from slow movement in supermarkets and groceries. This makes the peanut butter industry specifically more vulnerable to the new and more affordable spreads that have entered the market. With this and the changing breakfast food patterns from bread with spreads to the more convenient and varied instant "no-cook" noodles, porridges, biscuits, and cookies, peanut butter stands to lose its hold on its market. The market for peanut butter has remained relatively steady in the past years. The entry of breakfast substitutes like instant noodles, however, have led companies to be more creative. Players have learned to address consumer demand and preference for more nutritious and healthier foods by fortifying their products with Vitamins A, B1, D3, and E. Another is the introduction of peanut butter with stripes of chocolate and fruit jams like guava and grape, notably from Unilever Bestfoods. And since bread and spreads go hand-in-hand, another hope for the peanut butter industry is the expected growth the bread industry will post in the medium term. Packaging is also a potential growth consideration. Store checks revealed that peanut butter substitutes like sandwich spreads, mayonnaise, and cheese spreads have been enjoying tremendous sales after manufacturers, particularly Unilever Bestfoods and Kraft, introduced these in smaller retail packs at a cheaper cost. Reports say Unilever is positioning its marketing strategy towards the mass market. This strategy clicked with its shampoos in sachets and is expected to enjoy the same success in its mayonnaise, sandwich spread, and the recently launched Bestfoods Say Cheez cheese spread in sachets. It would not be a bad idea if peanut butter producers adopt a similar scheme and experiment by introducing peanut butter in sachets. Currently, the smallest peanut butter available is in 150-gram containers. Institutional users could also be tapped to widen the spread's market. Jams, jellies, and marmalades have been successful in this part. A leading player revealed that part of his company's growth plans is tapping toll-packers and entering into private labeling agreements with supermarkets and food stores. What the industry needs is to maintain producing high quality peanut butter coupled with a little marketing push. The development of more varieties and a touch of advertising could definitely help it compete with more popular spreads. WHAT IS LATENT DEMAND AND THE P.I.E.? The latent demand for peanut butter is not actual or historic sales. Nor is latent demand future sales. In fact, latent demand can be lower either lower or higher than actual sales if a market is inefficient (i.e., not representative of relatively

- 5. competitive levels). Inefficiencies arise from a number of factors, including the lack of international openness, cultural barriers to consumption, regulations, and cartel-like behavior on the part of firms. In general, however, latent demand is typically larger than actual sales in a country market. As mentioned in the introduction, this study is strategic in nature, taking an aggregate and long-run view, irrespective of the players or products involved. If fact, all the current products or services on the market can cease to exist in their present form (i.e., at a brand-, R&D specification, or corporate-image level) and all the players can be replaced by other firms (i.e., via exits, entries, mergers, bankruptcies, etc.), and there will still be an international latent demand for peanut butter at the aggregate level. Product and service offering details, and the actual identity of the players involved, while important for certain issues, are relatively unimportant for estimates of latent demand. THE METHODOLOGY In order to estimate the latent demand for peanut butter on a worldwide basis, I used a multi-stage approach. Before applying the approach, one needs a basic theory from which such estimates are created. In this case, I heavily rely on the use of certain basic economic assumptions. In particular, there is an assumption governing the shape and type of aggregate latent demand functions. Latent demand functions relate the income of a country, city, state, household, or individual to realized consumption. Latent demand (often realized as consumption when an industry is efficient), at any level of the value chain, takes place if an equilibrium in realized. For firms to serve a market, they must perceive a latent demand and be able to serve that demand at a minimal return. The single most important variable determining consumption, assuming latent demand exists, is income (or other financial resources at higher levels of the value chain). Other factors that can pivot or shape demand curves include external or exogenous shocks (i.e., business cycles), and or changes in utility for the product in question. Ignoring, for the moment, exogenous shocks and variations in utility across countries, the aggregate relation between income and consumption has been a central theme in economics. The figure below concisely summarizes one aspect of problem. In the 1930s, John Meynard Keynes conjectured that as incomes rise, the average propensity to consume would fall. The average propensity to consume is the level of consumption divided by the level of income, or the slope of the line from the origin to the consumption function. He estimated this relationship empirically and found it to be true in the short- run (mostly based on cross-sectional data). The higher the income, the lower the average propensity to consume. This type of consumption function is labeled "A" in the figure below (note the rather flat slope of the curve). In the 1940s, another macroeconomist, Simon Kuznets, estimated long-run consumption functions which indicated that the marginal propensity to consume was rather constant (using time series data across countries). This type of consumption function is show as "B" in the figure below (note the higher slope and zero-zero intercept). The average propensity to consume is constant. Is it declining or is it constant? A number of other economists, notably Franco Modigliani and Milton Friedman, in the 1950s (and Irving Fisher earlier), explained why the two functions were different using various assumptions on intertemporal budget constraints, savings, and wealth. The shorter the time horizon, the more consumption can depend

- 6. on wealth (earned in previous years) and business cycles. In the long-run, however, the propensity to consume is more constant. Similarly, in the long run, households, industries or countries with no income eventually have no consumption (wealth is depleted). While the debate surrounding beliefs about how income and consumption are related and interesting, in this study a very particular school of thought is adopted. In particular, we are considering the latent demand for peanut butter across some 230 countries. The smallest have fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. I assume that all of these counties fall along a "long-run" aggregate consumption function. This long-run function applies despite some of these countries having wealth, current income dominates the latent demand for peanut butter. So, latent demand in the long-run has a zero intercept. However, I allow firms to have different propensities to consume (including being on consumption functions with differing slopes, which can account for differences in industrial organization, and end-user preferences). Given this overriding philosophy, I will now describe the methodology used to create the latent demand estimates for peanut butter. Since ICON Group has asked me to apply this methodology to a large number of categories, the rather academic discussion below is general and can be applied to a wide variety of categories, not just peanut butter. Step 1. Product Definition and Data Collection Any study of latent demand across countries requires that some standard be established to define “efficiently served”. Having implemented various alternatives and matched these with market outcomes, I have found that the optimal approach is to assume that certain key countries are more likely to be at or near efficiency than others. These countries are given greater weight than others in the estimation of latent demand compared to other countries for which no known data are available. Of the many alternatives, I have found the assumption that the world’s highest aggregate income and highest income-per-capita markets reflect the best standards for “efficiency”. High aggregate income alone is not sufficient (i.e., China has high aggregate income, but low income per capita and can not assumed to be efficient). Aggregate income can be operationalized in a number of ways, including gross domestic product (for industrial categories), or total disposable income (for household categories; population times average income per capita, or number of households times average household income per capita). Brunei, Nauru, Kuwait, and Lichtenstein are examples of countries with high income per capita, but not assumed to be efficient, given low aggregate level of income (or gross domestic product); these countries have, however, high incomes per capita but may not benefit from the efficiencies derived from economies of scale associated with large economies. Only countries with high income per capita and large aggregate income are assumed efficient. This greatly restricts the pool of countries to those in the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), like the United States, or the United Kingdom (which were earlier than other large OECD economies to liberalize their markets). The selection of countries is further reduced by the fact that not all countries in the OECD report industry revenues at the category level. Countries that typically have ample data at the aggregate level that meet the efficiency criteria include the United States, the United Kingdom and in some cases France and Germany. Latent demand is therefore estimated using data collected for relatively efficient markets from independent data sources (e.g. Euromonitor, Mintel, Thomson Financial Services, the U.S. Industrial Outlook, the World Resources Institute, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, various agencies from the United Nations, industry trade associations, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank). Depending on original data sources used, the definition of “peanut butter” is established. In the case of this report, the data were reported at the aggregate level, with no further breakdown or definition. In other words, any potential product or service that might be incorporated within peanut butter falls under this category. Public sources rarely report data at the disaggregated level in order to protect private information from individual firms that might dominate a specific product-market. These sources will therefore aggregate across components of a category and report only the aggregate to the public. While private data are certainly available, this report only relies on public data at the aggregate level without reliance on the summation of various category components. In other words, this report does not aggregate a number of components to arrive at the “whole”. Rather, it starts with the “whole”, and estimates the whole for all countries and the world at large (without needing to know the specific parts that went into the whole in the first place). Given this caveat, this study covers “peanut butter” as defined by the North American Industrial Classification system or NAICS (pronounced “nakes”). For a complete definition of peanut butter, please refer to the Web site at http://www.icongrouponline.com/codes/NAICS.html. The NAICS code for peanut butter is 3119114. It is for this definition of peanut butter that the aggregate latent demand estimates are derived. “Peanut butter” is specifically defined as follows:

- 7. 3119114 peanut butter 31191141 peanut butter 3119114111 peanut butter in consumer sizes 3119114121 peanut butter in commercial sizes and bulk Step 2. Filtering and Smoothing Based on the aggregate view of peanut butter as defined above, data were then collected for as many similar countries as possible for that same definition, at the same level of the value chain. This generates a convenience sample of countries from which comparable figures are available. If the series in question do not reflect the same accounting period, then adjustments are made. In order to eliminate short-term effects of business cycles, the series are smoothed using an 2 year moving average weighting scheme (longer weighting schemes do not substantially change the results). If data are available for a country, but these reflect short-run aberrations due to exogenous shocks (such as would be the case of beef sales in a country stricken with foot and mouth disease), these observations were dropped or "filtered" from the analysis. Step 3. Filling in Missing Values In some cases, data are available for countries on a sporadic basis. In other cases, data from a country may be available for only one year. From a Bayesian perspective, these observations should be given greatest weight in estimating missing years. Assuming that other factors are held constant, the missing years are extrapolated using changes and growth in aggregate national income. Based on the overriding philosophy of a long-run consumption function (defined earlier), countries which have missing data for any given year, are estimated based on historical dynamics of aggregate income for that country. Step 4. Varying Parameter, Non-linear Estimation Given the data available from the first three steps, the latent demand in additional countries is estimated using a “varying- parameter cross-sectionally pooled time series model”. Simply stated, the effect of income on latent demand is assumed to be constant across countries unless there is empirical evidence to suggest that this effect varies (i.e., . the slope of the income effect is not necessarily same for all countries). This assumption applies across countries along the aggregate consumption function, but also over time (i.e., not all countries are perceived to have the same income growth prospects over time and this effect can vary from country to country as well). Another way of looking at this is to say that latent demand for peanut butter is more likely to be similar across countries that have similar characteristics in terms of economic development (i.e., African countries will have similar latent demand structures controlling for the income variation across the pool of African countries). This approach is useful across countries for which some notion of non-linearity exists in the aggregate cross-country consumption function. For some categories, however, the reader must realize that the numbers will reflect a country’s contribution to global latent demand and may never be realized in the form of local sales. For certain country-category combinations this will result in what at first glance will be odd results. For example, the latent demand for the category “space vehicles” will exist for “Togo” even though they have no space program. The assumption is that if the economies in these countries did not exist, the world aggregate for these categories would be lower. The share attributed to these countries is based on a proportion of their income (however small) being used to consume the category in question (i.e., perhaps via resellers). Step 5. Fixed-Parameter Linear Estimation

- 8. Nonlinearities are assumed in cases where filtered data exist along the aggregate consumption function. Because the world consists of more than 200 countries, there will always be those countries, especially toward the bottom of the consumption function, where non-linear estimation is simply not possible. For these countries, equilibrium latent demand is assumed to be perfectly parametric and not a function of wealth (i.e., a country’s stock of income), but a function of current income (a country’s flow of income). In the long run, if a country has no current income, the latent demand for peanut butter is assumed to approach zero. The assumption is that wealth stocks fall rapidly to zero if flow income falls to zero (i.e., countries which earn low levels of income will not use their savings, in the long run, to demand peanut butter). In a graphical sense, for low income countries, latent demand approaches zero in a parametric linear fashion with a zero- zero intercept. In this stage of the estimation procedure, low-income countries are assumed to have a latent demand proportional to their income, based on the country closest to it on the aggregate consumption function. Step 6. Aggregation and Benchmarking Based on the models described above, latent demand figures are estimated for all countries of the world, including for the smallest economies. These are then aggregated to get world totals and regional totals. To make the numbers more meaningful, regional and global demand averages are presented. Figures are rounded, so minor inconsistencies may exist across tables. Step 7. Latent Demand Density: Allocating Across Cities With the advent of a “borderless world”, cities become a more important criteria in prioritizing markets, as opposed to regions, continents, or countries. This report also covers the world’s top 2000 cities. The purpose is to understand the density of demand within a country and the extent to which a city might be used as a point of distribution within its region. From an economic perspective, however, a city does not represent a population within rigid geographical boundaries. To an economist or strategic planner, a city represents an area of dominant influence over markets in adjacent areas. This influence varies from one industry to another, but also from one period of time to another. Similar to country-level data, the reader needs to realize that latent demand allocated to a city may or may not represent real sales. For many items, latent demand is clearly observable in sales, as in the case for food or housing items. Consider, again, the category “satellite launch vehicles.” Clearly, there are no launch pads in most cities of the world. However, the core benefit of the vehicles (e.g. telecommunications, etc.) is "consumed" by residents or industries within the world's cities. Without certain cities, in other words, the world market for satellite launch vehicles would be lower for the world in general. One needs to allocate, therefore, a portion of the worldwide economic demand for launch vehicles to regions, countries and cities. This report takes the broader definition and considers, therefore, a city as a part of the global market. I allocate latent demand across areas of dominant influence based on the relative economic importance of cities within its home country, within its region and across the world total. Not all cities are estimated within each country as demand may be allocated to adjacent areas of influence. Since some cities have higher economic wealth than others within the same country, a city’s population is not generally used to allocate latent demand. Rather, the level of economic activity of the city vis-à-vis others. 1 INTRODUCTION 10 1.1 Overview 10 1.2 What is Latent Demand and the P.I.E.? 10 1.3 The Methodology 11 1.3.1 Step 1. Product Definition and Data Collection 12 1.3.2 Step 2. Filtering and Smoothing 13 1.3.3 Step 3. Filling in Missing Values 13 1.3.4 Step 4. Varying Parameter, Non-linear Estimation 13 1.3.5 Step 5. Fixed-Parameter Linear Estimation 14 1.3.6 Step 6. Aggregation and Benchmarking 14 1.3.7 Step 7. Latent Demand Density: Allocating Across Cities 14

- 9. 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 16 2.1 The Worldwide Market Potential 16 Raw Materials The peanut, rich in fat, protein, vitamin B, phosphorus, and iron, has significant food value. In its final form, peanut butter consists of about 90 to 95 percent carefully selected, blanched, dry-roasted peanuts, ground to a size to pass through a 200-mesh screen. To improve smoothness, spreadability and flavor, other ingredients are added, including include salt (1.5 percent), hydrogenated vegetable oil (0.125 percent), dextrose (2 percent), and corn syrup or honey (2 to 4 percent). To enhance peanut butter's nutritive value, ascorbic acid and yeast are also added. The amounts of other ingredients can vary as long as they do not add up to more than 10 percent of the peanut butter. Peanut butter contains 50 to 52 percent fat, 28 to 29 percent protein, 2 to 5 percent carbohydrate, and 1 to 2 percent moisture. The Manufacturing Process Planting and harvesting peanuts • 1 Peanuts are planted in April or May, depending upon the climate. The peanut emerges as a plant followed by a yellow flower. After blooming and then wilting, the flower bends over and penetrates the soil. The peanut is formed underground. Peanuts are harvested beginning in late August, but mostly in September and October, during clear weather, when the soil is dry enough so it will not adhere to the stems and pods. The peanuts are removed from vines by portable, mechanical pickers and transported to a peanut sheller for mechanical drying. • 2 Peanuts from the pickers are delivered to warehouses for cleaning. Blowers remove dust, sand, vines, stems, leaves, and empty shells. Screens, magnets, and size graders remove trash, metal, rocks, and clods. After the cleaning process, the peanuts weigh 10 to 20 percent less. The raw, cleaned peanuts are stored unshelled in silos or warehouses.

- 10. George Washington Carver, left, and industrialist Henry Ford share a weed sandwich in this 1942 photograph. For George Washington Carver, peanuts were a means to several ends. Throughout his career, Carver searched for ways to make small Southern family farms, often African-American owned, self-sufficient. Carver's popularization of peanuts and peanut products was part of his effort to free small farmers from dependence on commercial products and debt. It was also part of his effort to wean farmers away from the annual production of soil-depleting staple crops like cotton and tobacco. Carver's list of peanut products—from peanut milk and makeup to paint and soap— represented a wide range of household activities. Carver's interest in peanuts began in the mid-1910s, after he had pursued much research and education about other crops, especially sweet potatoes. A well- organized peanut industry lobby heard of Carver's work and capitalized on their mutual interest in the promotion of peanuts. Carver became the unofficial spokesman and publicist for the industry, especially after his 1921 appearance at tariffs hearings conducted by the U.S. House of Representatives' Ways and Means Committee. Facing alternatively bemused and hostile questioning from legislators, the African-American scientist eloquently and humorously explained the social, economic, and nutritional benefits of the domestic cultivation and consumption of peanuts. What evolved into a lunchtime favorite for kids was thrust into national prominence through one industry's search for growth and one man's search for economic independence for his people. William S. Pretzer

- 11. Shelling and processing • 3 Shelling consists of removing the shell (or hull) of peanuts with the least damage to the seed or kemels. The moisture of the The first several steps in peanut butter manufacture involve processing the main ingredient: the peanuts. After harvesting, the peanuts are cleaned, shelled, and graded for size. Next, they are dry roasted in large ovens, and then they are transferred to cooling machines, where suction fans draw cooling air over the peanuts. unshelled peanuts is adjusted to avoid excessive brittleness of the shells and kernels and to reduce the amount of dust in the plant. The size-graded peanuts are passed between a series of rollers adjusted to the variety, size, and condition of the peanuts, where the peanuts are cracked. The cracked peanuts then repeatedly pass over screens, sleeves, blowers, magnets, and destoners,

- 12. where they are shaken, gently tumbled, and air blown, until all the shells and other foreign material (rocks, mudballs, metal, shrivels) are removed. • 4 The shelled peanuts are graded for size in a size grader. The peanuts are lifted and then oriented on the perforations of the size grader. The larger peanuts (the "overs") are sent to one trough, while the "troughs" are guided towards another trough. The peanuts are then graded for color, defects, spots, and broken skins. • 5 The peanuts are shipped in large bulk containers or sacks to peanut butter manufacturers. (Inedible peanuts are diverted as oil stock in semibulk form.) To ensure proper size and grading, the truckloads transporting peanuts to peanut manufacturers are sampled mechanically. The sampler, testing two truckloads simultaneously, can quickly and accurately assess size and grading by examining 10 samples per truckload. If edible peanuts need to be stored for more than 60 days, they are placed in refrigerated storage at 34 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit (2 to 6 degrees Celsius), where they may be held for as long as 25 months. Shelled, the remaining peanuts weigh 30 to 60 percent less, occupy After the peanuts are roasted and cooled, they undergo blanching—removal of the skins by heat or water. The heat method has the advantage of removing the bitter heart of the peanut. Next, the blanched peanuts are pulverized and

- 13. ground with salt, dextrose, and hydrogenated oil stabilizer in a grinding machine. After cooling, the peanut butter is ready to be packaged. 60 to 70 percent less space, and have a shelf life about 60 to 75 percent shorter than unshelled peanuts. Making peanut butter • 6 The peanut butter manufacturers first dry roast the peanuts. Dry roasting is done by either the batch or continuous method. In the batch method, peanuts are roasted in 400-pound lots in a revolving oven heated to about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (426.6 degrees Celsius). The peanuts are heated at 320 degrees Fahrenheit (160 degrees Celsius) and held at this temperature for 40 to 60 minutes to reach the exact degree of doneness. All the nuts in each batch must be uniformly roasted. Large manufacturers prefer the continuous method, in which peanuts are fed from the hopper, roasted, cooled, ground into peanut butter and stabilized in one operation. This method is less labor-intensive, creates a more uniform roasting, and decreases spillage. Still, some operators believe that the best commercial peanut butter is obtained by using the batch method. Since peanut butter may call for a blending of peanuts, the batch method allows for the different varieties to be roasted separately. Furthermore, since peanuts frequently come in lots of different moisture content which may need special attention during roasting, the batch method can also meet these needs readily. The steps outlined below apply to peanut butter manufacturing that uses the batch method of roasting. Cooling and blanching • 7 A photometer indicates when the cooking is complete. At the exact time cooking is completed, the roasted peanuts are removed from heat as quickly as possible in order to stop cooking and produce a uniform product. The hot peanuts then pass from the roaster directly to a perforated metal cylinder (or blower-cooler vat), where a large volume of air is pulled through the mass by suction fans. The peanuts are brought to a temperature of 86 degrees

- 14. Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius). Once cooled, the peanuts pass through a gravity separator that removes foreign materials. • 8 The skins (or seed coats) are now removed with either heat or water. The heat blanching method has the advantage of removing the hearts of the peanuts, which contain a bitter principle. • Heat blanching: Depending on the variety and degree of doneness desired, the peanuts are exposed to a temperature of 280 degrees Fahrenheit (137.7 degrees Celsius) for up to 20 minutes to loosen and crack the skins. After cooling, the peanuts are passed through the blancher in a continuous stream and subjected to a thorough but gentle rubbing between brushes or ribbed rubber belting. The skins are rubbed off, blown into porous bags, and the hearts are separated by screening. Water blanching: A newer process than heat blanching, water blanching was introduced in 1949. While the kernels are not heated to destroy natural antioxidants, drying is necessary in this process and the hearts are retained. The first step is to arrange the kernels in troughs, then roll them between sharp stationary blades to slit the skins on opposite sides. The skins are removed as a spiral conveyor carries the kernels through a one-minute scalding water bath and then under an oscillating canvas-covered pad, which rubs off their skins. The blanched kernels are then dried for at least six hours by a current of 120 degrees Fahrenheit (48.8 degrees Celsius) air. • 9 The blanched nuts are mechanically screened and inspected on a conveyor belt to remove scorched and rotten nuts or other undesirable matter. Light nuts are removed by blowers, discolored nuts by a high-speed electric color sorter, and metal parts by magnets. Grinding • 10 Most of the devices used for grinding peanuts into butter are built so they can be adjusted over a wide range—permitting the variation in the quantity of peanuts ground per hour, the fineness of the product, and the amount of oil freed from the peanuts. Most grinding mills also have an automatic feed for

- 15. peanuts and salt, and are easy to clean. To prevent overheating, grinding mills are cooled by a water jacket. Peanut butter is usually made by two grinding operations. The first reduces the nuts to a medium grind and the second to a fine, smooth texture. For fine grinding, clearance between plates is about .032 inch (.08 centimeter). The second milling uses a very high-speed comminutor that has a combination cutting-shearing and attrition action and operates at 9600 rpm. This milling produces a very fine particle with a maximum size of less than 0.01 inch (.025 centimeter). To make chunky peanut butter, peanut pieces approximately the size of one- eighth of a kernel are mixed with regular peanut butter, or incomplete grinding is used by removing a rib from the grinder. At the same time the peanuts are fed into the grinder to be milled, about 2 percent salt, dextrose, and hydrogenated oil stabilizer are fed into the grinder in a continuous, horizontal operation, with about plus or minus 2 percent accuracy, and are thoroughly dispersed. • 11 Peanuts are kept under constant pressure from the start to the finish of the grinding process to assure uniform grinding and to protect the product from air bubbles. A heavy screw feeds the peanuts into the grinder. This screw may also deliver the deaerated peanut butter into containers in a continuous stream under even pressure. From the grinder, the peanut butter goes to a stainless steel hopper, which serves as an intermediate mixing and storage point. The stabilized peanut butter is cooled in this rotating refrigerated cylinder (called a votator),from 170 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit (76.6 to 48.8 degrees Celsius) or less before it is packaged. Packaging • 12 The stabilized peanut butter is automatically packed in jars, capped, and labeled. Since proper packaging is the main factor in reducing oxidation (without oxygen no oxidation can occur), manufacturers use vacuum packing. After it is put into final containers, the peanut butter is allowed to remain

- 16. undisturbed until crystallization throughout the mass is completed. Jars are then placed in cartons and placed in product storage until ready to be shipped out to retail or institutional customers. Quality Control Quality control of peanut butter starts on the farm through harvesting and curing, and is then carried through the steps of shelling, storing, and manufacturing the product. All these steps are handled by machines. While complete mechanical harvesting, curing, and shelling may have some disadvantages, the end result is a brighter, cleaner, and more uniform peanut crop. In the United States, strict quality control has been maintained on peanuts for many years with cooperation and approval from both the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Quality control is handled by the Peanut Administrative Committee, which is an arm of the USDA. Raw peanut responsibility rests with the Department of Agriculture. During and after manufacture, quality control is under the supervision of the FDA. In its definition of peanut butter, the FDA stipulates that seasoning and stabilizing ingredients must not "exceed 10 percent of the weight of the finished food." Furthemore, the FDA states that "artificial flavorings, artificial sweeteners, chemical preservatives, added vitamins, and color additives are not suitable ingredients of peanut butter." A product that does not conform to the FDA's standards must be labeled "imitation peanut butter." Byproducts Peanut vines and leaves are used for feed for cattle, sheep, goats, horses, mules, and other livestock because of high nutritional value. Peanut shells accumulate in great quantities at shelling plants. They contain stems, peanut pops, immature nuts and dirt. These shells are used mainly for fuel for the boiler generating steam for making electricity to operate the shelling plant. Limited markets exist for peanut shells for roughage in cattle feed, poultry litter, and filler in artificial fire logs. Potential additional uses are pet litter, mushroom-growing medium, and floor-sweeping compounds.

- 17. The Future In the United States and most of the 53 peanut-producing countries in the world, the production and consumption of peanuts, including peanut butter, is increasing. The quality of peanuts continues to improve to meet higher standards. The convenience peanut butter offers its users and its high nutritional value meet the demands of contemporary lifestyles. The use of peanuts as food is being introduced to remote parts of the world by American ambassadors, missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers. Some developing countries, understanding that their food protein scarcity will not be solved through animal proteins alone, are interested in growing the protein-rich peanut crop. Read more: How peanut butter is made - material, ingredients of, manufacture, making, used, processing, parts, steps, product, industry, machine, Raw Materials http://www.madehow.com/Volume-1/Peanut- Butter.html#ixzz1Av7AhQtW 2011 Report on Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Current State of the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Industry This section provides answers to the fundamental and commonly-asked questions about the industry: 1. What is the total market size ($ millions)? 2. Has the market grown or declined? 3. What is the market growth rate? 4. Are long term forecasts positive or negative? 5. What is the industry size and average company size? 6. How many companies are in the industry? Market Size - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing The total U.S. market size for the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry includes all companies, both public and private. In addition to total revenue, the table contains details on employees, companies, and average firm size.

- 18. Charts and graphs can be copied to Microsoft Word and Powerpoint presentations. Metrics 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Market Size (Total Industry Sales) Total Firms INCLUDED Total Employees Order at top of page Average Revenue Per Firm Average Employees Per Firm Source: Analysis of US Census data, updated June 8 2011 Market Forecast - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing[PREMIUM] Market forecasts show the long term outlook for the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry. The following five-year forecast utilizes advanced econometric techniques that take into account both short-term and long-term industry trends.

- 19. Forecast 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Market Forecast ($ millions) INCLUDED Source: AnythingResearch Economic Analysis Product Mix Product Description Sales (000) Percent Additional Information Roasted Nuts And Peanut Butter Manufacturing INCLUDED Nuts And Seeds (Salted, Roasted, Cooked, Or Blanched) INCLUDED Nuts (Salted, Roasted, Cooked, Or Blanched), Sold In Bulk INCLUDED Canned Nuts (Salted, Roasted, Cooked, Or Blanched) INCLUDED All Other Packaged Nuts, Including All Types Of Seeds INCLUDED Nuts And Seeds (Salted, Roasted, Cooked, Or Blanched), Not Categorized INCLUDED Peanut Butter INCLUDED Peanut Butter, Consumer Sizes INCLUDED Peanut Butter, Commercial Sizes And Bulk INCLUDED Peanut Butter, Not Categorized INCLUDED Roasted Nuts And Peanut Butter Manufacturing, Not Categorized, Total INCLUDED

- 20. Roasted Nuts & Peanut Butter Mfg, Not Categorized, For Nonadmin-Records INCLUDED Roasted Nuts & Peanut Butter Mfg, Not Categorized, For Admin-Records INCLUDED Geographic Distribution: Revenue by State Market Size by State ($ millions) indicates how the industry is distributed throughout the country. Move mouse over states to see revenue numbers Income Statement (Average Financial Metrics) - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Financial metrics provide a snapshot view of an "average" company in the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry. Key business metrics show revenue and operating costs. The data collected is industry- wide, covering both public and private companies in the industry. Industry Average Percent of Sales

- 21. Total Revenue Operating Revenue Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit Operating Expenses Pension, profit sharing plans, stock, annuity Repairs Rent paid on business property Charitable Contributions Depletion Domestic production activities deduction Advertising Compensation of officers Salaries and wages INCLUDED Order at top of page Employee benefit programs Taxes and Licenses Bad Debts Depreciation Amortization Other Operating Expenses Total Operating Expenses Operating Income Non-Operating Income EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) Interest Expense Earnings Before Taxes Income Tax Net Profit Source: Analysis of U.S. federal statistics Financial Ratio Analysis - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Financial ratios can be used to compare how a company in the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry is performing relative to its peers. Financial ratios are calculated from the industry-average for income statements and balance sheets. Liquidity Ratios - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Industry Average Manufacturing Industry

- 22. Liquidity Ratios measure how liquid a business is. Bankers and suppliers may use these to determine creditworthiness and identify potential threats to a company's financial viability. Current Ratio Included Measures a firm's ability to pay its debts over the next 12 months. Quick Ratio (Acid Test) Included Calculates liquid assets relative to liabilities, excluding inventories. Efficiency Ratios - Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Industry Industry Average Efficiency Ratios measure how quickly products and services sell, and effectively collections policies are implemented. Receivables Turnover Ratio Included If this number is low compared to the industry average, it may mean your payment terms are too lenient or that you are not doing a good enough job on collections. Average Collection Period Included Based on the Receivables Turnover Ratio, this estimates the collection period in days. Calculated as 365 divided by the Receivables Turnover Ratio Inventory Turnover Ratio Included A low turnover rate may point to overstocking, obsolescence, or deficiencies in the product line or marketing effort. Fixed-Asset Turnover Ratio Included Generally, a higher ratio is better, since it indicates the business has less money tied up in fixed assets for each dollar of sales revenue. Compensation & Salary Surveys for Employees Working in Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Compensation statistics provides an accurate assessment of jobs in the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry and national salary averages. This information can be used to asses which positions are most common, and high, low, and average annual wages. Average Percent of Bottom Upper Title (Median) Workforce Quartile Quartile Salary

- 23. Management occupations 5% Chief executives 0% General and operations managers 1% Office and administrative support occupations 11% Installation, maintenance, and repair occupations 5% INCLUDED Production occupations 41% Order at top of page Food batchmakers 8% Packaging and filling machine operators and tenders 11% Transportation and material moving occupations 22% Packers and packagers, hand 6% Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Companies in Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing and Adjacent Industries[PREMIUM] Company Address Key Contact INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED Public Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing Company News Web scan for recent news about publicly traded companies in the Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing industry. Government Contracts Related to Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing In 2010, the federal government spent a total of $39,156,085 on Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing. It has awarded 81 contracts to 28 companies, with an average value of $1,398,432 per company. Top government vendors: Company Federal Contracts Total Award Amount INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

- 24. Recent News about Roasted Nuts and Peanut Butter Manufacturing • Research and Markets: Updated Report on the Other Snack Food Manufacturing Industry in the U.S. and Its International ...:DUBLIN----Research and Markets has announced the addition of Supplier Relations US, LLC's new report "Other Snack Food Manufacturing Industry in the U.S. and its International Trade" to their offering. • Research and Markets: The Other Snack Food Manufacturing Industry's Revenue for the Year 2008 Was Approximately $18.4 ...:DUBLIN----Research and Markets has announced the addition of Supplier Relations US, LLC's new report "Other Snack Food Manufacturing Industry in the U.S. and its International Trade [Q4 2009 Edition ]" to their offerin