Of Blood and Magma | Mount.ai:n

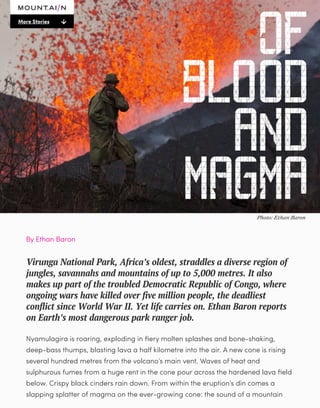

- 1. Photo: Ethan Baron By Ethan Baron Virunga National Park, Africa’s oldest, straddles a diverse region of jungles, savannahs and mountains of up to 5,000 metres. It also makes up part of the troubled Democratic Republic of Congo, where ongoing wars have killed over five million people, the deadliest conflict since World War II. Yet life carries on. Ethan Baron reports on Earth’s most dangerous park ranger job. Nyamulagira is roaring, exploding in fiery molten splashes and bone-shaking, deep-bass thumps, blasting lava a half kilometre into the air. A new cone is rising several hundred metres from the volcano’s main vent. Waves of heat and sulphurous fumes from a huge rent in the cone pour across the hardened lava field below. Crispy black cinders rain down. From within the eruption’s din comes a slapping splatter of magma on the ever-growing cone: the sound of a mountain Of Blood and Magma More Stories

- 2. A man with a machete passes a UN military convoy on a road next to Virunga National Park. The UN’s force of 20,000 in Democratic Republic of Congo, the largest peacekeeping operation in the world, has been unable to stop the violence tearing apart the country’s east. being born. It is January 2012. Some day, maybe tomorrow, perhaps not for decades, Nyamulagira will fall silent. Rain will erode the lava rock; soil will form. Grasses and shrubs will colonize the cone’s steep flanks. Banana shoots will sprout from cracks, jungle trees and vines will grow, then birds will appear, along with snakes, monkeys, chimpanzees and even mountain gorillas, if the volcano grows sufficiently tall. But this is eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and evil flows through this beautiful land, horror distilled from genocide and war, from tyranny, greed, poverty and hate, destroying nature, destroying people. In the villages, in the fields, along the roadsides, trauma is written on nearly every face.

- 3. Some 200 of the world’s 720 remaining mountain gorillas live in Virunga. IT IS 1982 and I’m lying in bed on a school day, burning with a mononucleosis fever, while the outlandish, violent jungle scenes of the novel Congo are seething to a hallucinatory intensity in my overheated teenaged brain: killer gorillas, laser- sighted robo-guns, wicked plunderers of the earth, the burgeoning life force of the jungle. I have no clue that in the country in which Michael Crichton’s tale takes place, the US-backed colonel Joseph Mobutu has been busy transforming Congo’s natural resources into a personal hoard worth billions and setting the stage for war. I have no inkling that one day I will walk in the jungles where Crichton’s story is set, in Africa’s oldest national park, the otherworldly and blood-soaked Virunga. In eastern Congo, where the western arm of the Great African Rift cracks the planet’s crust, equatorial life bursts riotously from the seam. More than 200 species of mammal and 700 bird species dwell in the jungles, mountains and savannahs within Virunga National Park, a wedge of land running 300 kilometres from north to

- 4. south within the rift, along the Uganda and Rwanda borders. Here, in one of the largest and deepest biodiversity stores on earth, are mountain gorillas, lowland gorillas, chimpanzees, lions, leopards, elephants and hippos. Here, too, is that other ape, that species born along the very same rift, that bipedal hominid which surpasses all creatures in the capacity to create and to destroy: Homo sapiens, the beast called Man. More than 200 species of mammal and 700 bird species dwell in the jungles, mountains and savannahs within Virunga National Park. Here, in one of the largest and deepest biodiversity stores on earth, are mountain gorillas, lowland gorillas, chimpanzees, lions, leopards, elephants and hippos. Virunga National Park ranger Urbain Butsitsi is firing his Kalashnikov into the forest. He hears long bursts of gunshots from the attacking mai mai militiamen concealed among the trees and undergrowth, sees glimpses of human shapes. An arrow whispers past, and another. A mai mai machine gunner opens up. It is October 2011, and Butsitsi, 25, has been a full-fledged park ranger for three weeks. Eight of his fourteen comrades now fighting six dozen militiamen are equally green. But special-forces training for rangers is a key component of his warden’s crusade to regain control of the park. While the mai mai spray wild salvos from their assault rifles, Butsitsi’s is switched to single-shot, and he is firing with care: “Bang, bang.” Slowly. “Bang, bang.” After five hours of fighting, three mai mai are dead and the militia retreats. Eleven Virunga rangers died in gunfights and ambushes in 2011 and another was killed in May 2012; since 1995, nearly 150 have died. Along roads running through and beside the park, militiamen murder several citizens a week during robberies. But in a region infamous for brutal conflicts, a bright spot is spreading. Virunga warden Emmanuel de Merode, a Belgian prince with a Ph.D. in biological anthropology, is asserting control over broad swathes of the park, regions crawling with militias either operating or protecting networks of poaching, illegal tree- cutting and fishing, all while robbing, raping and killing at will. Against the armed groups, de Merode has arrayed his new, slimmed-down, trained-up ranger army: 280 men, 84 of them aged 19 to 25 and hired in 2011. De Merode estimates he’s

- 5. taken back 80 per cent of the park, including large areas — and the park headquarters — overrun by rebels in late 2008. Progress is bumpy. Until recently, Virunga was at the epicentre of war for more than 15 years.

- 6. Under Mobutu, the park, founded in 1925, initially prospered. The dictator enjoyed hosting heads of state amid Virunga’s beauty and wildlife. But Mobutu’s greed and government corruption were drawing Congo toward collapse. Rebellions, then wars, would devastate flora and fauna. Hippo populations plunged from 23,000 in 1989 to 11,000 in 1994. After the 1994 genocide by Hutus of Tutsis next door in Rwanda, 700,000 Hutus fled a vengeful Tutsi army into Congo, spawning massive refugee camps on the border of Virunga. Refugees cut up to a thousand tons of timber daily in the park while poachers laid waste to wildlife for bush meat. The animal biomass in the park’s savannah areas, once four times greater than in the Serengeti, would plummet 90 per cent as conflicts continued. In the camps, the Hutu génocidaires were reorganizing and rearming into the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR). IT IS 1996, and I’m standing with one foot in Uganda and the other in Congo, after

- 7. slogging six hours up the Uganda side of the 3,645-metre extinct Sabinyo volcano at the junction of the Uganda, Congo and Rwanda borders. I am filthy, tired and sweaty from climbing through montane forest, then scaling pitch after pitch of rickety nailed branch ladders that reach upward through a fantasyland of freakish giant lobelia spears and towering leafy-headed groundsels. Thirty or so FDLR are now blasting at the outnumbered rangers. After 40 minutes of heavy fighting, the militiamen vanish into the jungle. The rangers have won the battle, but Badirushaka, a married father of five, is dead. From the rolling countryside of Rwanda to the south comes the distant sound of artillery and a heavy machine gun, as Tutsi government troops battle Hutu fighters bent on retaking the country. But it is westward toward Congo that I mostly gaze. Below me lies the jungle of those waking mono-fever dreams. By now I know Congo’s violence makes Crichton’s book look tame. And beneath the jungle canopy, the First Congo War is about to begin. I’m on my first journalism trip overseas. I’m not ready for war. Still, I feel Congo’s pull. Fifteen Virunga rangers are deep in the jungle searching for a charcoal-making operation. It is April 2011. In a region where nearly all cooking and heating is fuelled by trees, the FDLR-run charcoal trade is worth tens of millions of dollars — $30 million in nearby Goma alone, de Merode estimates. Virunga Park supplies most of Rwanda’s charcoal as well. As the ranger patrol climbs a hill, a voice shouts, “Who are you?” and a Kalashnikov begins to fire. Ranger Magayane Badirushaka takes a copper-jacketed slug in a buttock that tears into his abdomen. Ranger patrol leader Sekibibi Bareke dispatches four men to carry Badirushaka away and try to stop his bleeding. Of the 30 or so FDLR now blasting at the outnumbered rangers, Bareke can see only three, but the direction of incoming fire shows the gunmen are trying to surround them. After 40 minutes of heavy fighting, the militiamen vanish into the jungle. The rangers have won the battle, but Badirushaka, a married father of five, is dead. After Rwanda’s new Tutsi government kicked off the First Congo War by invading Congo in 1996, Rwandan soldiers and allied Congolese militias chased hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees from the camps and are alleged by the UN to have

- 8. Children in a squalid, cholera-ridden internal refugee camp in Rutshuru. Four months after this photo was taken, rebels burned the camp to the ground and drove the refugees into the jungle. slaughtered tens of thousands, génocidaires and innocents alike. Mobutu was overthrown in 1997 and Congolese rebel leader Laurent Kabila installed as president. A year later, the Second Congo War erupted, a savage six-nation squabble over the country’s vast mineral and timber wealth. Some five million people died through violence, disease and starvation. Kabila was assassinated in 2001; his son Joseph took his place. Conflict waned in 2003, but Virunga continued to suffer the depredations of armed groups and refugees who carried on widespread poaching and forest-clearing. By 2005, only 900 hippos remained in the park. Nineteen mountain gorillas were killed in five separate incidents in 2007. In 2008, the forces of Congolese Tutsi warlord Laurent Nkunda swept through the region. After overrunning the Congolese army base at Rumangabo, Nkunda’s troops attacked the adjacent Virunga Park headquarters. Rangers fled into the jungle. Nkunda was captured in early 2009. Renegade Congolese army general Bosco Ntaganda replaced him. Fighting between Ntaganda’s militia and Congolese troops led warden de Merode to evacuate non-Congolese headquarters staff for a week in March 2012, and shut two ranger posts near the mountain-gorilla sector two months later.

- 9. Virunga National Park rangers travel on high alert through an area frequented by murderous perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide. In spring 2012, heavy fighting erupted once again between government and rebel troops. By July, the park was closed to the public, temporarily, it is hoped. In spring 2012, de Merode deployed his newest weapon against poachers and militias. After a year of training, Virunga’s man-tracking bloodhounds went operational in March, trailing poachers from an elephant killed for ivory. The pursuit led to a firefight and seizure of four rifles left by the fleeing suspects. The dog unit’s five hounds — two of them from Ontario — and the ranger dog team have been trained by Marlene Zähner of Switzerland, arguably the world’s best bloodhound trainer. Zähner, 52, spends two weeks every two months in the park, honing the skills of rangers and hounds. “Here it’s so dangerous that you really have to have everything perfect,” Zähner

- 10. says. Dogs and handlers are trained to find their quarry, then back off and let their heavily armed ranger colleagues attempt capture. The hounds face significant risk, and de Merode admits some may die. The dogs’ lives, like those of the rangers, are on the line in the service of a critical conservation effort, the warden argues. An alcove has been hollowed out of the embankment above a potholed dirt road running north to Lake Edward. It is June 2011. The three rangers riding in a park truck don’t see the FDLR until a gunman in the hollow opens fire. One ranger escapes, one is shot in the head and left by the militia for dead. The third ranger lies wounded in the road. Within minutes, a UN military patrol arrives at the scene. The FDLR are gone. The ranger in the road has had his head cut off. I see Kalashnikovs, another machine gun and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. I raise my camera toward the man. Then I look into his eyes and see hatred so fierce I am instantly certain if I shoot him he’ll shoot me. I lower the camera. It is 2008, and I am in the passenger seat of a hired Land Cruiser, driving slowly past a dreadlocked FDLR génocidaire draped in bullets and holding a machine gun. He stands under a huge spreading tree by this dirt road on the edge of Virunga. I have come up from Goma, a city sprawling over lava fields, where a young woman in hospital has told me of being gang-raped and sexually mutilated by men just like this one. Congo’s two multi-nation wars are over, but the east remains a violent maelstrom, as FDLR, the Congo army, mai mai and Nkunda’s rebels fight for dominance. I’m riding in the middle of a four-jeep UN military convoy carrying sixteen Indian Army soldiers armed with assault rifles and two mounted machine guns. Behind the militiamen a half dozen fighters sit in the shade on the buttress roots of the tree. I see Kalashnikovs, another machine gun, and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. I raise my camera toward the man beside the road. Then I look into his eyes, and see hatred so fierce I am instantly certain if I shoot him he’ll shoot me. I lower the camera. On an early evening in February 2011, a truck carrying 15 rangers in the park’s central region drives into a storm of bullets. Outgunned by the 30 or so attackers,

- 11. the rangers — three of them wounded — flee into the bush. A ranger search team arrives after dark. They find all their comrades but one: Katchupa Changwi, a 40- year-old married father of three. Changwi is seen leaping from the truck amid the gunfire. He is found the next day. Shot in the calf, he had hobbled from the ambush and bled to death overnight. Mai mai are formidable and familiar with the terrain in which they operate, says Gilbert Dilis, 52, a former Belgian parachute commando who served in Rwanda during the genocide. But the FDLR, numbering up to 700 in and around the park and with leaders from the pre-genocide Rwandan army, pose the greatest threat, he says. “They have military training. They are in the jungles since 1994. They are specialists of the guerrilla warfare. Every day and every time is dangerous here.” IT IS 2012 and I am remembering Nyamulagira, and desolation in an old man’s eyes; young gorillas spinning round on jungle vines, a gang-raped girl with her bladder burst by a mai mai’s hand; liquid-gold sunrise on a swimming hippo’s back, and the deadly promise in a gunman’s stare. I am remembering Virunga and the people risking their lives to preserve it: Zähner, with the hounds; de Merode, the prince obsessed; Dilis, who saw too much but still came back for more; and especially the rangers, working, and dying, for $160 a month. Maybe some day, not tomorrow, perhaps not for decades, the evil will be gone. Share ‘Of Blood and Magma’ CONTRIBUTORS Ethan Baron is a Vancouver-based journalist and photojournalist, recently departed from a daily-newspaper job to devote more time to work in foreign climes. Of Blood and Magma was published in the Winter 2012/13 edition of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine, the Radical Issue. /

- 12. you@yours.com * Holding Radical Ideas Moore’s Code Articles Archive About Sign up for new article news: ©2015 KMC Productions